Evolution expert Professor Lawrence C Scharmann argues pedagogical practices should be adopted to ensure the development of positive learning environments.

Every teacher of the theory of evolution has an opportunity – and an obligation – to point out some of the practical implications of Darwinian theory for human conduct. A thoughtful biologist cannot fail to find (in Shakespeare’s words) “… tongues in trees, books in the running brooks, sermons in stones….” If he is interested in people as well as in things – and a teacher should be, even if a researcher is not – he will want to help students hear the sermons evolution.

Readiness to teach evolution

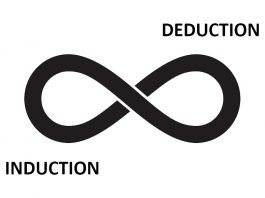

A simple but effective technique for self-assessing readiness to teach a particular topic is to explicitly reflect on the student questions, ‘Why do I need to know this stuff?’ and ‘What’s in it for me?’ Faced with these questions, real or implied, instructional decisions should be made to better address and reflect the needs of target learners. If the teacher’s response does not have sufficient perceived relevance to the target learner, students find it quite easy to dismiss the ‘stuff’ as unimportant – something to be memorised for a test and forgotten. Preparation to teach evolution often carries with it an implicit additional question: ‘Why should I believe this stuff?’ An inadequate response to this question can undermine a teacher’s credibility and compromise one’s rapport with students and parents alike. How then should one prepare?

One can address the situation academically by promoting evolution as one of the most powerful working tools available to the practicing biologist. The introduction of subsequent topics such as genetics, ecology, and animal behaviour, for example, need to be tied directly to their roots in evolutionary theory. Too often teachers make the mistake of treating such topics as though they have no relationship to evolutionary biology. This approach is insufficient alone, nonetheless, because it does not directly acknowledge students’ emotional reactions to a topic of study they may perceive as controversial or about which they have preconceived (often inaccurate) conceptions. Accounting for students’ emotional responses in advance prevents potential defensive reactions that can hinder (or even damage) student and teacher relationships.

Critical instructional relationships

Relationships between students and teachers are important in creating classroom atmospheres of trust and co-operation. Opening ourselves up to students requires us to be aware of our own emotions, to observe and interpret students’ emotions, and to cope with students’ feelings as they are expressed. All of these are demanding and important – if rarely acknowledged – aspects of teaching.

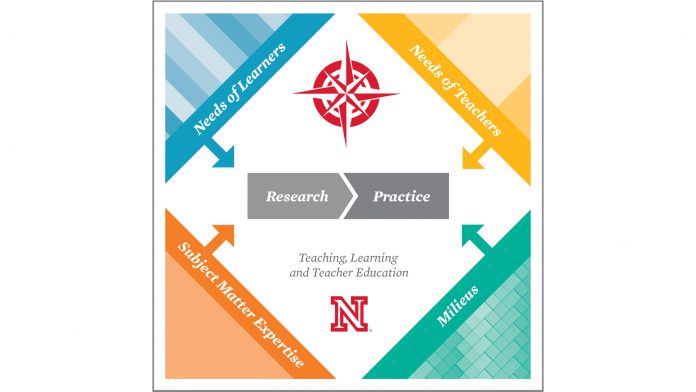

If an instructional environment that is conducive to learning generally requires the development of good student-teacher relationships, then a classroom atmosphere of trust is an especially important consideration when we engage students in the teaching and learning of evolution. Emotional scaffolding, therefore, is crucial to the successful teaching and learning of evolution. Quinlan (2016) refers to four key relationships necessary to construct this scaffolding – students with teachers being merely one of the four key relationships comprising a comprehensive emotional scaffolding – the others being students with subject matter, students with other students, and students with their developing selves.

Recognition and a nurturing of these four relationships to manage students’ emotional responses to evolution instruction demand that instructors:

- Develop relationships in an appropriate sequence – teacher-student and subject-student first, followed by student-student, and finally nurturing students with developing selves; and

- Use non-threatening assessments that allow students to privately express their honest feelings about the science being learned.

The teacher-student relationship begins on the first day of class. I often refer to it as the second worst day of the semester. From that first day, I systematically engage students in activities that enhance individual curiosity and build student-subject relationships, require collective problem-solving, and initiate opportunities for students to begin a social construction of possible responses to problems and puzzles (i.e., initiate student-student interactions). Each subsequent class session (hopefully) fosters positive conversations, builds mutual trust, and creates a nascent sense of being a part of a mutually supportive cohort. I get to know which students work well together and alter student-student learning interactions accordingly. If I have successfully created this sense of community over time, then the last day of the semester is the worst for both me and for my students, because there comes the reckoning that our time together has drawn to a close … and to give it up is ultimately bittersweet.

The most difficult relationship to accomplish is that of students with their developing selves. This relationship requires pre-existing, established trust between teachers and individual students. Nonetheless, with that trust in place, I recommend the use of journaling as a non-threatening assessment in relation to teaching evolutionary biology.

In their journals, students are encouraged to respond to three focus questions:

- What aspects of the nature of science did you observe in the lessons/activities this week?

- What influence did the recent class activity and discussion have on your understanding of evolution? And

- Has your view of evolution changed? Explain your response and provide support for (or examples of) what influenced the change.

Students are required to provide appropriate evidence to use as justification for any claims made in their journal entries. Students also receive frequent reassurance, as they study topics such as evolution, the environment, genetically modified organisms, etc., that it is perfectly valid, in making their journal entries, to accept or reject any scientific claim as long as the decision was based on sound argument and evidence. Instructor feedback is often restricted to reminding students to use observations directly from the class activities, especially in cases where students reject a specific scientific claim. This use of journaling with non-judgmental feedback provides students with a safe outlet to reflect on their perceptions of what they were experiencing in class and how they are emotionally responding to it. As students learn more about what evolution is/is not, the vast majority of students transition from little to no understanding of evolutionary theory to a recognition that scientific theories (such as evolution) play an important role in providing us with tools to answer scientific questions and solve scientific puzzles.

A reprise of essay themes

This current essay completes a set of four connected narratives that comprise a distillation of my recommendations for enhancing the teaching of evolutionary biology. First, as one builds an initial teacher-student relationship, I recommend teaching (reinforcing) the nature of science immediately prior to introducing study of evolutionary theory (see Essay One).4 Second, I suggest introducing evolution as an example of how scientists apply theory in explaining patterns in scientific evidence and answering scientific questions (see Essay Two).5 Third, I recommend introducing the abstract notion of necessary uncertainty and iterative refinement (i.e., self-correction) as key properties of all scientific research (see Essay Three).6 Finally, I urge adopting pedagogical practices that ensure the development of positive learning environments (current essay).

References

- Hardin, G. (1973). ‘Ambivalent aspects of evolution’. American Biology Teacher, 35, 15-19

- Quinlan, KM (2016). ‘How emotion matters in four key relationships in teaching and learning in higher education’. College Teaching, 64:3, 101-111

- Scharmann, LC & Butler, W. (2015). ‘The use of journaling to assess student learning and acceptance of evolutionary science’. Journal of College Science Teaching, 45:1, 11-16

- Scharmann, L.C. (2020). ‘Theories – a powerful tool for science’. The Innovation Platform, 3, 164-165. www.innovationnewsnetwork.com/publication/the-innovation-platform-issue-3/

- Scharmann, L.C. (2020). ‘Evolutionary theory in applied problem solving’. The Innovation Platform, 4, 182-183. www.innovationnewsnetwork.com/publication/the-innovation-platform-issue-4

- Scharmann, L.C. (2021). ‘Evolutionary theory: Coping with a pandemic’. The Innovation Platform, 5, 158-159. www.innovationnewsnetwork.com/publication/the-innovation-platform-issue-5/

Please note, this article will also appear in the sixth edition of our quarterly publication.