Professor Lawrence C Scharmann from the University of Nebraska talks about why scientists keep changing their minds about COVID-19 recommendations and the importance of reliable data.

In the previous edition of The Innovation Platform, I delineated how biologists, infectious disease specialists, and healthcare professionals make use of the evolutionary principle of common ancestry as a problem-solving lens. We apply this lens each time we encounter an infectious disease. The first question to be asked is whether the disease is already known. If it is known we can mitigate the spread of the disease based on existing strategies (e.g. quarantining, isolation, vaccination). If it is new, however, the next question posed is: ‘does this new disease at the very least closely resemble other known diseases?’ Asking this secondary question and identifying logical similarities permits the potential development of a vaccine more quickly than it would otherwise occur – this happens yearly, for example, with strains of influenza. When the answer, however, is that the infectious disease is completely novel and not sufficiently resembling an already known disease, the work to create viable vaccines becomes more daunting, time-consuming, and requires rigorous protocols of clinical trials in sequential phases.

The Spanish Flu

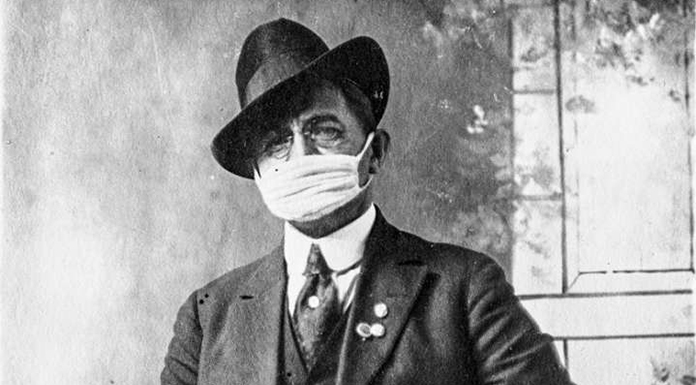

There was a time in history when influenza A was an unknown, novel virus. We now know it to be an example of an H1N11 virus of avian origin.2 This specific novel virus, labelled the Spanish Flu, caused a pandemic between 1918 and 1919 in which deaths numbered nearly 50 million worldwide. Lacking a vaccine, known therapeutics, or other medicines to effectively treat influenza A, mitigation techniques consisted of the widespread use of face coverings (masks, cloth kerchiefs, bandanas) and the practice of physical distancing when in public spaces. These two simple mitigation techniques were used to ‘flatten the curve’ of infectious transmission and slow the spread of the disease. Sound familiar?

The high number of deaths resulting from the Spanish Flu, it is speculated, might have been caused by a cytokine storm produced in the body. A cytokine storm, or hypercytokinemia, is a physiological immune response in which excessive quantities of cytokine (a normal part of the human immune infectious response) overwhelmed and caused multisystem organ failure. Thankfully, today, since we now have multiple examples of influenza viruses, infectious disease specialists can monitor outbreaks, identify subtypes (e.g. H1N1, H1N2, H3N1, H2N3), and produce seasonal vaccines with reasonable certainty that they will provide protection against severe infection. The yearly effectiveness of a flu vaccine, nonetheless, varies from year to year, depending on how closely the new influenza virus resembles known influenza strains.

COVID-19 (a coronavirus)

In a 1948 speech to the British House of Commons, Winston Churchill, paraphrasing a 1905 maxim attributed to George Santayana, asserted: “Those who fail to learn from history are condemned to repeat it.”3

Early in 2020, nations across the globe were warned about the potential for a pandemic arising from a novel virus that originated in Wuhan, China. The virus began an inevitable steady march of infection locally, regionally, nationally, and eventually internationally. Questions posed earlier in this essay were appropriately applied:

- Is the infectious disease one that is already known? Answer: no.

- Does the infectious disease (at the very least) closely resemble other known diseases? Answer – other than the virus possessing a distinguishing corona or halo when viewed under electron microscopy – no.

Thus, other than identifying the morphological shape of the virus, it was identified as novel. The official name, 2019 coronavirus disease, is shortened to a designation of type and year of discovery, or COVID-19.4

Lacking existing known strategies to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic, infectious disease specialists recommended immediate ‘shelter in place’ shutdowns. The purpose of the shutdowns was to minimise disease spread and (of equal importance) to gain valuable time to further examine the structure and characteristics of COVID-19 that could result in greater specificity concerning those mitigation strategies that would have the most efficacious effects in slowing the spread of the disease.

Scientists changing their minds

Initial data obtained from Europe and Asia were inconclusive regarding how long COVID-19 would remain viable/virulent:

- As droplets suspended in the air (and at what distance one would be safe in proximity to other people)

- On various surfaces (e.g., door handles, light switches, food packaging, grocery bags)

- Through interpersonal physical transfer/touch.

Without more data, the specificity of recommendations could not be reliably determined. Early in the pandemic, for example, it was recommended that we physically distance at six to10 feet, wear a face covering, wipe down our grocery purchases with a disinfectant, avoid handshakes, not gather in numbers greater than 100. One year later, we are not as concerned about touching items at the grocery store; nor do we feel the need to wipe down our grocery purchases with a disinfectant. In addition, the number of individuals gathering indoors changed to 50 and then 10. Universities and schools spent part of the spring and all summer of 2020 trying to follow changing guidelines for safely reopening. Why the changes in the recommendations? Because we had learned, through collected data and experiences with COVID-19, what the most effective tools were for slowing the spread, flattening the curve, and mitigating the rate of infection.

It has been determined that COVID-19 is a highly infectious, airborne virus, that cares nothing about politics, mental fatigue, or an infringement on personal liberties. Until viable effective vaccines are fully distributed and administered to 70% or more of the world’s population in order to achieve herd immunity,5 the best tool we have in our arsenal to mitigate the pandemic remains wearing a simple face covering when in public spaces, while physically distancing at a minimum of six feet and keeping large gatherings to a minimum to avoid unnecessary ‘super-spreading’ events of the COVID-19 virus. However, because of political differences, economic concerns, human desires for contact and normalcy, and even selfish behaviours, the rates of infection and mortality due to COVID-19 will continue to spike – again and again – in various geographic regions of planet Earth until herd immunity can be achieved.

Will there be a need for another shutdown? Do we need to return to shelter in place policies? Not necessarily – but we need, collectively as a population of local, regional, national, and international citizens, to be on the same page with one another in order to avoid renewed needs for shutdowns and shelter in place mandates. Now that we have more reliable data, we can, with prudence, reopen with modest normalcy with an eye to the realities of a virus that has a mind of its own and cares not one lick about what we want or who we are. One cannot simply wish COVID-19 away – no matter how much we might want to do so.

References

- The designation letters ‘H’ and ‘N’ refer to glycoproteins haemagglutin and neuraminidase; and are described as H1N1, H1N2 depending on the type of H or N antigens they express

- https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-pandemic-h1n1.html

- https://winstonchurchill.org/resources/in-the-media/churchill-in-the-news/folger-library-churchills-shakespeare

- https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it

- The percentage of the world’s population needed to be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity differs with each infectious disease – for measles (95%); polio (80%) – https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/herd-immunity-lockdowns-and-covid-19#:~:text=Herd%20immunity%20is%20achieved%20by,without%20making%20us%20sick

Please note, this article will also appear in the fifth edition of our quarterly publication.