Matt Frost, Deputy Director and Head of Policy at the Marine Biological Association, highlights the importance of marine science for sustainable development.

On 31 March 1884, a group of eminent scientists gathered in a room at the Royal Society in London to form the Marine Biological Association (MBA). The man known as ‘Darwin’s Bulldog’ due to his advocacy of Darwin’s theory of evolution, Thomas Henry Huxley, was elected President, with Professor Edwin Ray Lankester accepting the position of MBA Secretary. This was no rarefied gathering of ivory-tower academics, however, as the newly formed society had support from the highest levels of government, including Joseph Chamberlain who was president of the Board of Trade in William Gladstone’s government.

Funding from the Board of Trade was also key to the MBA being able to build a new Laboratory in Plymouth, which was based on the Stazione Zoologica in Naples and was opened on 30 June 1888. This support was provided because it was understood that sustainability, and specifically the exploitation of the ocean’s resources (which had acted as the catalyst for the formation of the new society), needed to be high on the agenda – just as it is at the top of the international agenda today.

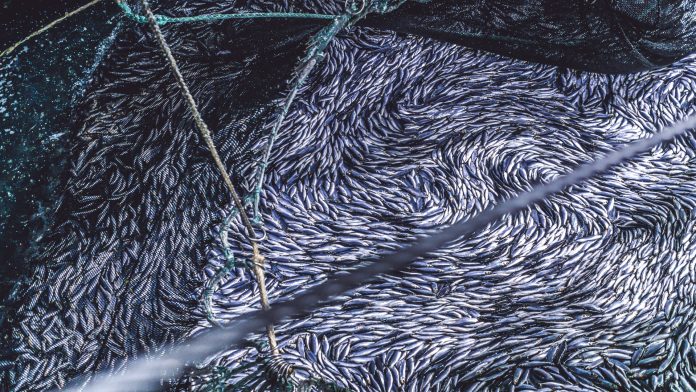

In the late 19th century, the argument was over the sustainability of fishing practices, with Huxley arguing that over-exploitation of the seas was not possible (at least not with the fishing practices at the time), whereas Lankester argued not only that over-exploitation of a particular fishery was a very real possibility, but that this could also impact other parts of the ocean ecosystem.

A modern global problem

Today, with rapid advances in technology and an ever-increasing demand on resources, over- exploitation of fisheries is a global problem, as are issues such as habitat destruction, pollution, and deep-sea mineral mining. The problem is also being addressed at the global level, with the United Nations (UN) adopting, in 2015, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development that includes 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Although a number of the SDGs are relevant to the marine environment, it is SDG14, ‘life below water’, which is focused purely on the sustainable use of oceans and seas. Again, this is no purely academic exercise, with the ocean recognised as being our planet’s largest life-support system and the economic value of the ocean estimated to increase from US$1.5 trillion in 2010 to US$3tr by 2030.1

© iStock/bigtunaonline

Earth’s last frontier

The obvious challenge in meeting the ambitious goals laid out in SDG14 is in coming up with workable plans and actions for the most unexplored environment on the planet – often referred to as ‘Earth’s last frontier’. In order to address this gap in knowledge, in 2017 the UN declared a ‘Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development’ from 2021 to 2030. The Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO (IOC-UNESCO) are leading on the Decade utilising the strapline ‘The Science We Need for the Ocean We Want’. The ocean we want part is relatively straightforward to articulate, being described as six desired societal outcomes:

- A clean ocean where sources of pollution are identified and removed;

- A healthy and resilient ocean where marine ecosystems are mapped and protected;

- A predictable ocean where society has the capacity to understand current and future ocean conditions

- A safe ocean where people are protected from ocean hazards;

- A sustainably harvested ocean ensuring the provision of food supply; and

- A transparent ocean with open access to data, information, and technologies.

It is the second half of the strapline, the science we need, where the challenges begin to appear.

Research and development challenges

Firstly, the R&D priorities identified to deliver the underpinning evidence are, quite understandably, extremely ambitious. R&D priority one, for example, is aimed at producing a ‘comprehensive map of the ocean’2, which given that we have only mapped about a fifth of the ocean so far, will be challenging to say the least.

There is also the issue that the project most likely to achieve this, Seabed 2030, funded by the Nippon Foundation, is only looking at a basic bathymetric map at this point, when the ultimate need is for a wider range of parameters in order to be of use for managers and decision-makers. Even where species distribution information is available for oceans, it is noted that global models are not often at high enough resolution to be useful at regional and local levels.3 There is no doubt that the ambition in terms of mapping and information gathering is appropriate if we really are to have a sustainable ocean plan. However, the challenges in delivery should not be underestimated.

What about the science?

Secondly, most of the work required in terms of science is not new in terms of being an identified gap. I have been involved in discussions since the early 2000s on better national and international level co-ordination and integration of observing systems, and it is hard to say things have improved.

The lack of funding for long-term marine observations was being highlighted back in the early 1990s4, and many of the science needs for the Ocean Decade were identified by the then Executive Secretary of the IOC, Gunnar Kullenberg, back in 1995, including:

- Better use of and access to data;

- Better co-ordination of observation systems;

- Better incorporation of science into policy and governance;

- The need for training and education; and

- The need for interdisciplinary research, including the need to incorporate social science.5

The most recent paper to bemoan the lack of integration of social science into fisheries and marine science generally was published in 2020, with a key point made in the paper being ‘the time for integrating social science into applied marine research is now.’6

Gullenberg was exactly right in 1995 when he stated that science is an important requirement for delivering sustainable development, and it is hoped that the next ten years can fill gaps, some of which were identified 25 years ago. There are, of course, new ‘gaps’ today, but new knowledge always raises new questions as new technologies open up new areas of discovery – this is not a ‘problem’, but rather a mark of progress, and is how science works.

Of course, the biggest challenges are always financial. This may be in absolute terms (can the requisite funding be found via governments, agencies or private/commercial sources); or in relative terms (we need funding to ensure that research is better distributed, thereby avoiding overlap and, indeed, to ensure that the research focuses on areas, geographical or otherwise, that we know little about, rather than on those for which we already have knowledge.)

There is also a political element to funding, which involves convincing those who have access to funds, particularly in government, that ocean research is a priority when a whole range of other policy priorities are clamouring for attention. Governments may talk about blue/green growth, but these concepts have developed over decades within the framework of sustainability without ever being clearly defined or applied.7 This is where science-policy dialogue is at its most crucial, as it relies on governments, industry, and academia all agreeing on the direction and priorities for research funding against an agreed outcome (that the sustainable use of our seas and oceans are commensurate with a blue/green growth agenda).

Continuing the evidence-based policy agenda

Over 135 years after its establishment, the MBA continues with the same ethos as when it started in promoting and undertaking science to inform sustainability. Excellent marine scientific research is the building block of any plans or policies developed for this sector, and there is thus a requirement to ensure that this information is provided to the various relevant stakeholders. Politicians and decision-makers need scientific evidence to develop policies and make decisions; the wider scientific community needs it to foster collaboration from the local to the international level; industry and the private sector need it to encourage synergies around co-design and co-funding; and the public need it to encourage the next generation of marine scientists (and to demonstrate the good use of money which, if from government, is public money).

It is for this reason that the MBA has chosen to engage with the UN Decade as a partner. In addition to our own scientific staff working at our laboratory headquarters, we are encouraging engagement via our 2,000 members in over 40 countries.

We are also developing plans to mobilise our nearly 800 Young Marine Biologists, recognising that, moving forwards, many of them will be the individuals delivering the goals of this decade. We are also working with our networks worldwide though activities such as the formal establishment of the World Association of Marine Stations to encourage global co-operation and contribute to the Decades resource base. Marine science for sustainability was at the heart of the MBA at its inception, and it is at the heart of what the MBA does today.

References

- OECD (2016), The Ocean Economy in 2030, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264251724-en. Accessed 20 July 2020

- Ryabinin Vladimir, Barbière Julian, Haugan Peter, Kullenberg Gunnar, Smith Neville, McLean Craig, Troisi Ariel, Fischer Albert, Aricò Salvatore, Aarup Thorkild, Pissierssens Peter, Visbeck Martin, Enevoldsen Henrik Oksfeldt, Rigaud Julie (2019). ‘The UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development’. Frontiers in Marine Science. 6: 470 URL=https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmars.2019.00470

- Claudet, Joachim, et al. (2020). ‘A roadmap for using the UN Decade of ocean science for sustainable development in support of science, policy, and action’. One Earth 2.1: 34-42

- Duarte, C., Cebrián, J. & MARBÀ, N. ‘Uncertainty of detecting sea change’. Nature. 356, 190 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1038/356190a0

- Kullenberg, G. (1995) ‘Reflections on marine science contributions to sustainable development’. Ocean & Coastal Management. Vol. 29 (1-3): pp. 35-49

- Kraan, M., Linke, S. ‘Commentary 2 to the manifesto for the marine social sciences: applied social science’. Maritime Studies (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-020-00182-2

- Eikeseta et al. ‘What is blue growth? The semantics of “Sustainable Development” of marine environments.’ Marine Policy (2018). 87:177–179. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2017.10.019

Matt Frost

Deputy Director and Head of Policy

Marine Biological Association

+44 (0) 1752 426493

info@mba.ac.uk

Tweet @thembauk

www.mba.ac.uk

Please note, this article will also appear in the third edition of our new quarterly publication.