The Circle of Health, a community-oriented approach to health promotion, opens new doors in refugee and migrant health and wellbeing

Over the past ten years, many refugees and migrants moved to Europe from war-torn countries, for economic benefits or other reasons. Due to conditions before, during, and after their journey (such as traumatic experiences, poverty, stress experienced en route, or unfavourable living conditions in crowded shelters in the target countries, as well as social isolation and/or discrimination) their health is often at risk. (1, 2) To assist with their integration and to promote their health, countless projects have been initiated throughout Europe. (3) However, most projects are stand-alone projects, targeting only one aspect of health and are not based on a common theoretical model of holistic health, making it very difficult to provide an overall picture of all health promotion projects, to evaluate programmes within in a country and to identify gaps. A conceptual framework that promises to integrate all health promoting projects and to stimulate more holistic and community-oriented approaches in health promotion and health literacy is the Circle of Health (CoH).4

Numerous anecdotal reports show that the CoH works, yet there is still a lack of systematically acquired scientific evidence as to why and how it works. This article shows how it can be applied and its benefits by drawing on case stories of its application in two sites in Germany.

The European Context and the uptake of the CoH

The CoH was developed in 1996 in Prince Edward Island, Canada to promote a shared understanding of health promotion; to assist people in locating links, relationships, and contributions promoting partnerships; and to provide direction for planning and evaluation, through a community/system partnership using principles of community development, adult education, and qualitative research. (5) The CoH includes the basic principles of health promotion laid out in the Ottawa Charter and also the determinants of health, crucial values, populations, and the dimensions of health. (6) It continues to be viewed as a relevant tool for working across sectors and cultures in promoting individual, community, and societal health and well-being.(7)

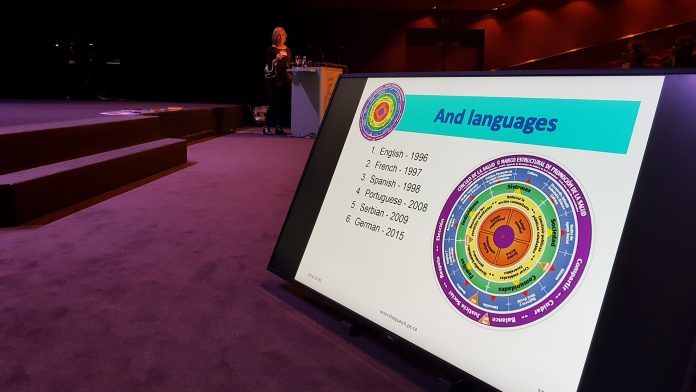

From its launch in 1996, the CoH generated national and international interest, resulting in translation into French and Spanish (1998), Portuguese (2008), and Serbian (2009). In 2016, new opportunities emerged during the IUHPE Conference in Curitiba, Brazil and the 6th Global Forum on Health Promotion, Charlottetown, Canada. At the same time, the CoH was discovered by a PhD candidate in Germany conducting a literature search for health promotion models/frameworks suitable for working with migrants and refugees. Subsequent German-Canadian collaboration resulted in online CoH workshops being offered as a credit course at Furtwangen University, Germany, validation of translation to German, and presentations during the European Public Health (EUPHA) Conference in Slovenia in 2018.4 An outcome of the EUPHA Conference was the inclusion of the CoH in the toolbox of the EU-funded Mig-HealthCare project (2019) and for pilot testing the CoH. The timing and context were right for collaboration amongst all authors of this article.

Case Story – Pilot of the CoH in the Mig-HealthCare project

The EU-funded project Mig-HealthCare was created in 2017 to, amongst other aims, identify and promote community-based healthcare and health promotion tools to improve refugee and migrant healthcare access. The CoH was chosen as a tool to be piloted by the NGO Ethno-Medizinisches Zentrum e.V. (Ethno-Medical Centre (EMZ)) in Germany. The purpose was to assess whether the CoH might be helpful in health promotion activities engaging migrants and refugees. Some migrant groups in Germany present a high prevalence of obesity and/or malnutrition, especially child obesity, which can lead to further health consequences like diabetes, hypertension and other related NCDs. (8, 9) As a consequence, healthy diet and physical activity were chosen as the subject and the pilot structured as a workshop on 14 February 2020 in Berlin.

The goals were:

- Creating shared understanding of health promotion among health professionals and migrants;

- Stimulating holistic, community-oriented approaches in health promotion;

- Exchanging knowledge and experience regarding migrant health; and

- Drafting recommendations for health promotion activities.

In preparation, Patsy Beattie-Huggan provided online coaching for the staff of EMZ and Stefanie Harsch provided support in designing the workshop. Representatives of various migrant communities and professionals from various fields of health promotion were invited. To gain access to migrant communities, intercultural health mediators trained in the course of the ‘MiMi’ (‘with migrants for migrants’) programme of the EMZ were chosen as key persons with sufficient German language skills and good knowledge of their community’s needs. (10)

Participants were first asked to brainstorm on ‘what they did for their health today’. This stimulated reflection on the different health dimensions (mental, emotional, physical, and spiritual) in the CoH core, and created a shared understanding and awareness of health as a multifaceted concept. After a short introduction on the Mig-HealthCare project and the aims of the pilot, participants worked in groups on a case study, which dealt with a community-based health issue in a fictitious setting. Participants were asked to make use of the CoH to assess the situation and find solutions.

During group discussion, key obstacles to promoting health for migrants were identified and solutions suggested. Participants reflected on the usefulness of the CoH in analysing problems and planning measures in regard to migrant communities. To conclude, they were asked to fill in a questionnaire to evaluate the workshop and the usefulness of the CoH.

Evaluation

The empirical data from the pilot showed that the CoH was successful in stimulating an exchange of knowledge between professionals and members of the migrant communities on a highly relevant topic in health promotion. Furthermore, the ‘Circle’ supported the whole process from designing the workshop and guiding and stimulating the discussion to supporting the groups in the workshop in gaining and sharing knowledge. Participants found the focus of the workshop and the categories and dimensions covered by the CoH highly relevant in respect to migrants, and the CoH was rated as a highly adaptable tool for collaborative measures solving health issues. Nevertheless, some participants felt unsure as to how the Circle could serve their daily work as a theoretical framework and a hands-on tool, which indicated the need for further training.

Case Story – Using the CoH to map offers and to bring people together

Collaboration in promoting the health of migrants and families is the aim of a new project offered in and around Freiburg, Germany, called ‘Gesundheitliche Prävention für Menschen mit Fluchterfahrung’. In recent years, many people in the area were committed to helping refugees and multiple programmes that promote health and its determinants were created. Not all actors knew each other, so it was very difficult to map the many programmes, to know the specifics of the programmes, and to develop a common, regional strategy. To achieve the goal of working together to promote health literacy, it became clear that:

- A framework/model was needed for the systematic description of local programmes; and

- Providers needed a common understanding and a shared language to communicate concisely.

When screening potential models for this purpose, the CoH was selected.

An online questionnaire was developed, within which each ring of the CoH guided closed and open questions about the target group, strategy, and determinants of health. This enabled the project to classify the entire range of programmes based on CoH dimensions, to produce a report, and to inform actors about others working similarly.

An online meeting of more than 50 participants from various professions was held on 30 June, 2020 to share the questionnaire findings and familiarise the participants with the CoH, to offer them a shared language, and to show ways in which the CoH could serve their own work. Information about the project and the questionnaire’s findings were shared, as well as a presentation on the CoH, its background, and components. Participants were invited to describe their programmes based on this model before being asked to reflect on their own practice and how they work with the target group to analyse their life circumstances; to develop suitable interventions; and to map all programmes. In an accompanying document, the participants received more detailed information on the CoH and suggestions on how to use the CoH for different purposes step by step.

Evaluation

Applying the CoH to systematically map health promotion programmes for migrants was beneficial. However, during the workshop it emerged that the CoH, while interesting, is also complex and that –at least for Germany – it is necessary to establish a holistic understanding of health amongst those working both directly and indirectly on the topic of the health of specific target groups. Due to the online format of the workshop and the short time available, it was not possible for small groups to work through a scenario with the CoH, but active engagement in applying the CoH is essential for wider uptake.

Conclusion

Based on the experience of the two case studies, application of the CoH has provided us with many lessons which can be applied in the future:

- It is confirmed that the CoH:

a) Contributes to the broader understanding of health and to freeing health promotion approaches from the narrow understanding of individual health-behaviour change;

b) Provides an excellent framework to initiate mapping health promotion programmes;

c) Provides users with a shared language which fosters collaboration; and

d) Stimulates the development of new ideas. - One workshop is a beginning, but more opportunities for active learning are required to develop confidence;

- Online learning, although effective, has limitations; holding the CoH in your hands and group interaction stimulates learning;

- Having the CoH in one’s first or dominant language facilitates its use; and

- A key limitation is that some practice areas, such as healthcare, are very highly regulated and allow few flexible changes, making it difficult to apply in these areas.

In summary, the CoH is a dynamic tool with the potential to expand the breadth of understanding of health to a more holistic model and inspire those working with migrant populations to reflect on their work and shape their attitude to health promotion activities. In the immediate global context, moving through and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, the CoH holds promise as an evidence-based tool for facilitating holistic, comprehensive planning to renew our approaches to population health and build a better future. As a priority next step, we recommend further dissemination of the CoH to communities, academics, and professionals, and documentation of how the CoH is used and its benefits in different settings.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge William Sherlaw, from the Public Health School in Rennes, France, who introduced the Circle of Health to the Mig-HealthCare Toolbox and proposed that it be pilot-tested. The EMZ wishes to acknowledge Prolepsis Institute, Greece, for the successful co-operation in the Mig-HealthCare project.

References

- Robert-Koch-Institut. Gesundheit und gesundheitliche Versorgung von Asylsuchenden und Flüchtlingen in Deutschland. Journal of Health Monitoring. 2017;2(1):24-47

- ‘Report on the health of refugees and migrants in the WHO European Region: No PUBLIC HEALTH without REFUGEE and MIGRANT HEALTH’. Copenhagen, Demark; 2018

- Riza E, Kalkman S, Coritsidis A, et al. ‘Community-Based Healthcare for Migrants and Refugees: A Scoping Literature Review of Best Practices’. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8(2). doi: 10.3390/healthcare8020115

- Beattie-Huggan P, Steinhausen K, Harsch S. ‘A framework for global health promotion: The Circle of Health’. RO. 2019;(107):118-121

- PEI Health and Community Services Agency. The Circle of Health: PEI’s Health Promotion Framework. Charlottetown; 1996

- WHO Europe. ‘Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion’; 1986; 4. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/129532/Ottawa_Charter.pdf. Accessed 05/02/2020

- Beattie-Huggan P. The Circle of Health – journey from behind the scenes, local to global impact in health promotion. Sci-Tech Europa Quarterly. 2019;(32)

- Robert-Koch-Institut. Migration und Gesundheit. Berlin: Robert-Koch-Institut; 2008. Schwerpunktbericht zur Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes. www.rki.de/DE/Content/Gesundheitsmonitoring/Gesundheitsberichterstattung/GBEDownloadsT/migration.pdf?__blob=publicationFile.20. Accessed 2007/07/2020

- Robert-Koch-Institut. Gesundheit in Deutschland; 2015. http://www.gbe-bund.de/pdf/GESBER2015.pdf Accessed 20/09/2020

- Salman R.’ Gesundheit mit Migranten für Migranten – die MiMi Präventionstechnologie als interkulturelles Health-Literacy-Programm’. Public Health Forum. 2015;23(2)

Authors

Patsy Beattie-Huggan, The Quaich Inc., Canada; Stefanie Harsch, University of Education Freiburg, Germany; David Brinkmann, Ramazan Salman, Ethno-Medizinisches Zentrum e.V., Hanover, Germany.

Patsy Beattie-Huggan

The Quaich Inc

+1 902 894 3399

patsy@thequaich.pe.ca

Tweet @TheQuaich

www.thequaich.pe.ca

Please note, this article will also appear in the fourth edition of our new quarterly publication.