Spectroscopic instruments are very sensitive tools which play an important and active role in exploring and understanding the Solar System.

One of the most challenging questions and motivation for exploring the Solar System and beyond is ‘Does or did life exist elsewhere than on Earth?’ Venus is often called Earth’s twin because its overall properties like mass and size are very similar to those of Earth. Meteorological and geological phenomena on the surface of Mars have similarities with Earth’s.

Our current understanding suggests that Mars, Earth, and Venus started out with comparable surface environments, geological processes, and atmospheric compositions. Yet, they evolved into very distinct states. Mars meets the minimum criteria for the existence of life, i.e. energy, surface water in the past (and possibly in the subsurface today), and nutrients, including carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulphur (CHNOPS). Venus may have been habitable in its early history, having hosted a global ocean. The enhanced D/H ratio in its atmosphere, however, suggests that the planet suffered a runaway greenhouse effect resulting in the loss of its ocean. On Mars, the shutdown of its internal dynamo and loss of its protective magnetic field is proposed to have contributed to the loss of the planet’s atmosphere.

Venus-size exo-planets may be common in the Universe. Studying Solar System bodies provides us with valuable information on the chemistry and potential habitability of exoplanets. Indeed, comparative planetology aims at a global understanding of the processes existing on planets or planet-like bodies through the observation of physical phenomena acting under a wide range of conditions (pressure and temperature, magnetic field, etc.) and forces (the distance to the Sun, for example). This also allows scientists to test models and understand the limits of our understanding.

Planetary science at the Royal Belgian Institute for Space Aeronomy

The Royal Belgian Institute for Space Aeronomy (BIRA-IASB), and in particular the Planetary Atmospheres Research Unit, has been leading research in planetary science for many years. It has been involved in the very first missions towards Mars and has increased its expertise in designing, building, and running space instrumentation. The expertise encompasses observations, such as remote sensing measurements of the characteristics of the atmospheres, as well as modelling.

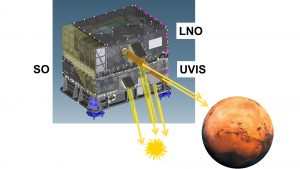

BIRA-IASB has been involved in the design and data investigation of several space spectroscopic instruments for the European Space Agency (ESA) – SPICAM on Mars Express, SPICAV-SOIR on Venus Express, MAJIS on JUICE and NOMAD on ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter 2016 – and is also collaborating on international projects (Phoenix, MAVEN/NASA, MMX/JAXA). In particular, BIRA-IASB is Principal Investigator for the SOIR/VeX and NOMAD/ExoMarsTGO instruments and for VenSpecH proposed for the next ESA M5 EnVision mission to Venus.

Spectroscopic remote sensing is the most adequate method to sound the composition of planetary atmospheres, especially in the UV and IR spectral ranges. This technique relies on laboratory measurements of reference spectroscopic data and on the development and implementation of up-to-date radiative transfer codes including aerosols and scattering as well as of algorithms to invert spectral data to geophysical products. Interpretation of the observed spectroscopic data is also based on atmospheric models (Mars GCM, cloud microphysics, ionospheric model, etc.).

Using spectroscopic instruments to search for biosignatures

The focus is placed on the neutral atmosphere from the surface of the planet to the upper layers, where escape processes to space have to be considered. Studying the composition of an atmosphere allows us to better understand the various processes at play. Spanning the UV, visible, and IR ranges, a long series of molecular species show absorption and emission features which allow for their identification and quantitative determination. Temperatures and pressures can be derived from the measurements. Through radiative absorption and emission processes, temperature will have an effect on the composition and, as a consequence, on the stability of the atmosphere and the clouds’ formation.

Having access to these quantities can be used to constrain models explaining the formation and evolution of planets. In particular, being able to characterise trace gases, i.e. gases with very low abundances, is fundamental to understanding the photochemistry taking place in atmospheres and to infer the planet’s past and current state of activity.

Detecting specific gases can also give hints on the habitability of a planet, i.e. its potential to harbour life. This search for biosignatures has become a new area of research also fueled by the improvements to the new exoplanets missions. One of the objectives of the NOMAD instrument1 on board ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter is the search for biomarkers. Covering a wide IR spectral range, the instruments looked for methane and other related trace gases like ethane or ethylene, which could be linked to biogenic processes.

A recent study2 showed that none of these species were detected, their abundances being below the detection limits of the spectroscopic instrument (0.06, 0.1 and 0.7 ppb, respectively). The new VenSpec-H instrument3 will be part of the recently selected ESA M5 mission, EnVision, which will explore Venus. Our instrument will sound the atmosphere, looking for water vapour and sulphuric species, to link these to volcanism or surface processes.

Dust and clouds are everywhere

In all known planets and celestial bodies, in our Solar System but also on exoplanets, dust and clouds play a crucial role in their atmospheres. Aerosols, suspensions of fine particles, can absorb and scatter light, participating actively in the radiative state of the atmosphere with a direct impact on the climate. Aerosols are also precursors of clouds by allowing condensation processes to occur on their surface. Clouds and dust are intimately related to the atmospheric composition, chemistry, structure (temperature), and circulation.

Our group is currently leading a European research project investigating the micro-properties of such particles and their impact on the dynamics through global circulation modeling as well as on the measurements performed by remote sensing instruments.4

Future missions

Mars, Venus, and the other planets of our Solar System have now been monitored for decades, either from Earth using large telescopes and sensitive spectrometers, from the Hubble Space Telescope, from rovers or platforms on their surface, and, of course, from instruments in orbit around them. Today, missions are being prepared which will survey the atmospheres of exoplanets with sensitive spectrometers that will measure the spectral signatures of these far away bodies. These will significantly benefit from the scientific knowledge and the technical developments done in the context of understanding our own Solar System. Going back to Venus, as has been recently decided by various space agencies, is certainly one crucial step towards understanding the diversity and complexity of the new worlds we will discover.

Acknowledgement

These studies would not be possible without the full support from the Belgian Science Policy Office (BELSPO). The RoadMap project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 101004052.

research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 101004052.

References

1. Nomad.aeronomie.be

2. www.esa.int/Science_Exploration/Human_and_Robotic_Exploration/

Exploration/ExoMars/ExoMars_orbiter_continues_hunt_for_key_signs_of_life_on_Mars

3. venspec.aeronomie.be

4. roadmap.aeronomie.be

Please note, this article will also appear in the seventh edition of our quarterly publication.