The latest eBook from Dr Carlos Ziebert, Head of the Calorimeter Center at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), explores how Europe’s largest battery calorimeter laboratory at KIT advances battery safety and thermal management through cutting-edge calorimetric testing and holistic thermal analysis.

With seven Accelerating Rate Calorimeters of different sizes – from coin cell to large pouch or prismatic automotive format – and extremely sensible Tian-Calvet calorimeters, the Battery Calorimeter Laboratory at the IAM-AWP of KIT offers the evaluation of thermodynamic, thermal and safety data for lithium-ion and post-lithium cells on material and cell level. These data can be used on all levels of the value chain – from the safe materials design up to the optimisation of the thermal management and the safety systems. Our fields of research encompass both normal conditions and abuse conditions:

Normal condition tests include:

■ Isoperibolic cycling, which provides constant environmental temperatures;

■ Quasiadiabatic cycling, which ensures that there is almost no heat exchange between the cell and the surroundings

Each of these allows:

■ Measurement of temperature curve and distribution for full cycles or application specific load profiles;

■ Determination of generated heat;

■ Separation of heat in reversible and irreversible parts; and

■ Ageing studies.

Abuse condition tests include:

■ Thermal abuse – Heat-Wait-Seek, thermal propagation test;

■ Electrical abuse – external short circuit, overcharge and overdischarge test, as well as

■ Mechanical abuse – nail penetration test.

Each of these allows:

■ Temperature measurement;

■ External or internal pressure measurement;

■ Gas collection and analysis;

■ Postmortem analysis; and

■ Ageing studies – change of risk potential with increasing ageing degree.

Introduction to the group Batteries – Calorimetry and Safety

The group Batteries – Calorimetry and Safety focuses on calorimetric investigations and safety tests on lithium-ion cells and post-lithium cells. Various types of calorimeters are used, depending on cell size and application. The group is interdisciplinary, well-connected across Germany and internationally, and takes a comprehensive approach ranging from fundamental studies to industrial applications.

The IAM-AWP Calorimeter Centre, led by Dr Ziebert, was founded in 2011 and operates Europe’s largest battery calorimeter laboratory, which contains seven Accelerating Rate Calorimeters (ARCs) of different sizes.

They allow the evaluation of thermodynamic, thermal and safety data for Lithium-ion cells on material, cell and pack levels under quasiadiabatic and isoperibolic environments for both normal and abuse conditions (thermal, electrical, mechanical). Since 2011, more than 300 thermal studies and safety tests have been performed on cells ranging from coin cell size over cylindrical cells to large pouch and prismatic automotive cells. As a result, this method has become so well established that the IAM-AWP is now one of the leading international institutions in the field of thermal runaway investigations, as reflected in numerous industrial contracts and invited lectures.

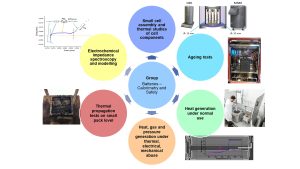

The group’s research can be categorised into six different areas (see Fig. 1). Starting with the assembly of small cells, the thermal properties of these are investigated. The research continues with comprehensive ageing tests, which include both calendar and cyclic ageing. The focus of the research is detailed studies on heat generation under normal and abuse scenarios, which can be performed with the help of different calorimeters. In addition, thermal propagation in small cell assemblies can be studied. Moreover, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and modelling approaches can be applied.

Importance of safe batteries

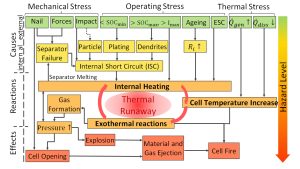

Safety comes first – this is the mission of the Centre’s head, Dr Carlos Ziebert. The development of safe lithium-ion cells is of utmost importance for a breakthrough in the electrification of transport and for stationary storage because an uncontrollable increase in temperature of the entire system (so-called thermal runaway) can cause an ignition or even explosion of the battery, with simultaneous release of toxic gases. Thermal runaway is a worst-case scenario that must be avoided under all circumstances, especially in an electric car or another electric vehicle, and the causes and effects of this can be very diverse and complex (Fig. 2). As such, it is crucial to conduct thermodynamic studies of the thermal effects together with the material and cell development for advanced lithium and post-lithium systems.

In the current state of lithium-ion technology, the range of properties is still significantly dependent on the respective operating and usage conditions (state of charge, age) as well as the ambient conditions. The influence of ageing on the safety of the cells is a critical factor in their commercial use. Even regular use of batteries with varying charge and discharge cycles under different operating and environmental conditions leads to the release of heat and sometimes critical temperature increases in the system. These effects are caused by electrochemical reactions, phase transformations, mixing and Joule heating processes. The active materials can initiate highly exothermic reactions dependent on the respective battery operating conditions and the ambient temperature by internal and external short circuits or mechanical action. This can be followed by the thermal runaway. To avoid such reactions, the system must be designed optimally with respect to the material and cell level. In addition, the battery management and cooling systems must be optimised to meet technical requirements. Thus, a complete scientific and technical understanding of these effects is essential.

Benefits of battery calorimetry

Calorimetry is fundamental to obtaining quantitative data on thermal behaviour – you need to know how many watts a cell will produce under certain conditions. This information can then be used to adapt the battery and thermal management systems. Sophisticated battery calorimetry allows the finding of new and quantitative correlations between different critical safety and thermally related parameters. Calorimetry – or the process of measuring heat data during chemical reactions – allows the collection of quantitative data required for optimum performance and safety. During the last few years, we have established battery calorimetry as a powerful and versatile electro-chemical-thermal characterisation technique that provides a holistic approach to advancements in the thermal management and safety of batteries.

In this way, safety can be improved, and the batteries can be operated for longer without malfunctioning. The transfer to newly developed materials and cells also shortens the time to the market. Fig.3 shows two of the Accelerating Rate Calorimeters (ARCs) at the IAM-AWP Battery Calorimeter Laboratory. In these ARCs, the evolution of temperature, heat, and internal pressure can be studied while operating cells under conditions of normal use, abuse, or accidents. These data are essential for battery, thermal management and safety system design. Combined with multiscale electro-chemical-thermal modelling they provide a powerful tool for thermal runaway prevention and ageing prediction.

Such abuse tests without a calorimeter have two main disadvantages:

■ The maximum safe temperature would be underestimated (i.e. the battery would be perceived to be less hazardous).

■ The thermal runaway consequences would be understated in terms of the severity and speed of the incident.

It should be highlighted that, unlike other simpler techniques like hot box tests, the Heat-Wait-Seek (HWS) in the ARC reveals the entire process of the thermal runaway with the different stages of exothermic reactions. It allows the separation of the different exothermic reactions instead of only getting an approximate temperature at which the cell goes into thermal runaway.

Europe’s largest battery calorimeter laboratory

At Europe’s largest Battery Calorimeter Laboratory (see Fig. 4) we have established a holistic approach for advancements in the thermal management and safety of batteries, as explained in Fig. 5. On the materials and components level, differential scanning calorimeters (DSC) from Netzsch and an extremely sensible C80 Tian-Calvet calorimeter from Setaram Instrumentation can be used to provide thermophysical parameters such as heat capacity and to analyse in detail the possible phase transformations and the thermal stability of new materials.

On the small-scale cell level, a larger-scale MS 80 Tian-Calvet calorimeter allows the determination of heat generation during cycling with great accuracy. The next level is robust adiabatic ARCs from Thermal Hazzard Technology that allow the evaluation of thermodynamic, thermal, and safety data on material and cell levels for normal and abusive conditions (thermal, electrical, mechanical). The lab encompasses further important infrastructures such as gloveboxes for cell assembly and disassembly, temperature chambers for different temperature ranges, and cyclers with several hundred channels and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) option.

Moreover, it contains gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy systems from Perkin-Elmer for venting gas analysis. With these facilities and the established expertise, the IAM-AWP is now – as seen worldwide – one of the few institutions that investigate both the thermodynamics and the safety of batteries and their materials. In recent years, the IAM-AWP has conducted pioneering work in this area. The ARCs can be used for studies on heat generation and dissipation of large single cells and are coupled to a battery cycler to perform the measurements during charging and discharging.

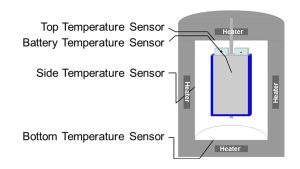

The recorded temperature profile serves as a “fingerprint” for the state of health (SOH) and as a fast and reliable method for the ageing characterisation. The tests can be performed during the charging and discharging of the cells under defined thermal conditions, which are a) quasiadiabatic or b) isoperibolic. The cell is inserted into the calorimeter chamber, which has heaters and thermocouples located in the lid, bottom and side walls (see Fig. 6) that adjust the required ambient conditions.

Quasiadiabatic Cycling

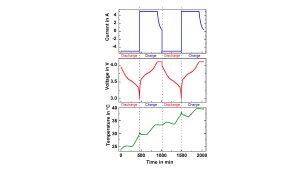

In the quasiadiabatic mode, the heaters in the calorimeter chamber immediately follow any change in the cell temperature, preventing the heat transfer to the chamber. This simulates ambient conditions for a cell in a pack, where the densely packed neighbouring cells prevent – or at least greatly reduce – the heat release to the environment. This leads to a continuous increase in the cell temperature with every cycle, as can be seen in Fig. 7a for a 40 Ah pouch cell.

Isoperibolic Cycling

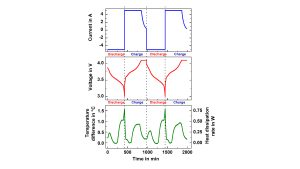

Isoperibolic means that the calorimeter walls are maintained by the heaters at a constant temperature while measuring the variation of the surface temperature of the cells, which is shown in Fig. 7b. In this case, the cell temperature reaches its initial temperature again after each cycle. Such data make it possible to optimise charge and discharge management and to analyse ageing processes. By measuring the specific heat capacity and the heat transfer coefficient, the temperature data can be converted into generated and dissipated heat data, which are needed to adjust the thermal management systems. E.g. in Fig. 7b, the heat dissipation rate is shown for a low C/8 discharge rate, reaching a maximum of 0.75 W.1

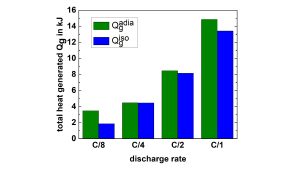

Integration over one discharge half-cycle gives a dissipated heat of 6.4 kJ and a total generated heat of 7.9 kJ. Fig. 8 shows the comparison of the total generated heat measured under isoperibolic and quasiadiabatic conditions for different C-rates. A good agreement between both methods can be found.

Abuse tests in battery calorimeters

Apart from important data that can be implemented into the battery management system (BMS), the battery calorimeters provide thermal stability data on a materials level, e.g. of anodes, cathodes or electrolytes or their combinations.2,3 They allow to perform safety tests on the cell level by applying:

A) Electrical abuse: External/ internal short circuit, overcharge/overdischarge

In the ARC, the temperature increases by applying an external short circuit or during an internal short circuit, which might be caused, e.g. by a production fault in the cell can be measured. Additionally, the cell can be overcharged or over-discharged by a battery cycler, leading to different failure modes.4

B) Mechanical abuse: Nail test

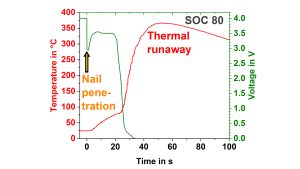

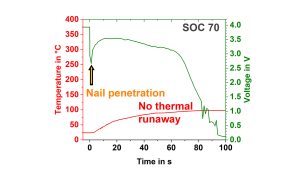

A mechanical system which enables to push a nail into the cell can be used to measure quantitative data during such a mechanical abuse test. Fig. 9a) and 9b) show the comparison of the temperature increase and the voltage behaviour during a nail penetration test on a pouch cell at an unsafe and safe state-of-charge (SOC). It can be clearly seen that at a SOC of 70%, the temperature increase is much smaller, and the cell does not go into thermal runaway as at a SOC of 80%. From the maximum temperature and the specific heat capacity, the heat of the reaction can be calculated to be 3.7kJ and 17.1kJ, respectively.

C) Thermal abuse: Heat Wait-Seek test, thermal propagation test

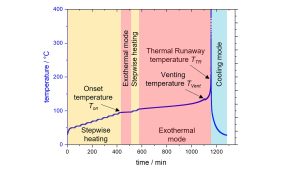

The Heat-Wait-Seek (HWS) test starts in the Heat mode by heating up the cell in 5°C temperature steps, as shown in Fig. 10. At the end of each step, the Wait Mode is activated for typically 30 min to reach thermal equilibrium. If it is below the previously set limit, the Heat-Wait-Seek loop restarts by heating the cell. When this limit is exceeded, the calorimeter goes into Exotherm Mode (quasiadiabatic conditions), and the heaters follow the temperature of the cell so that it cannot exchange heat with the environment and continues to heat up until the reactants are exhausted or the thermal runaway occurs.

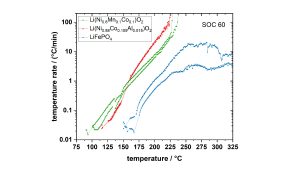

When exceeding the maximum ARC temperature, the cell gets cooled down by compressed air in the Cooling mode. The HWS test allows us to detect the different critical temperatures, which are the onset temperature, where the first exothermal reaction starts, the venting temperature and the temperature at which the cell goes into thermal runaway. Fig. 11 shows a comparison of the temperature versus time plots for 21700 cells with different cathode materials measured at a SOC of 60%.5 It can be clearly seen that the cells show different behaviour and that curves for the LiFePO4 cells are shifted to higher temperatures, which indicates that they are safer. The NMC cells show the lowest onset temperature of 90 °C, and the NCA cells go to thermal runaway at the lowest temperature, which is 220 °C.

cells with different cathode materials measured at a SOC of 60 %

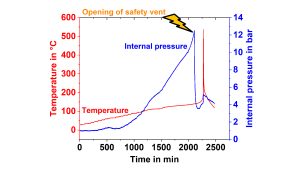

In addition, new methods for the measurement of internal cell pressures for early prediction of thermal runaway of LIB have been established on 18650 cells. A pressure line connected to a pressure transducer was directly inserted into the cell, and the pressure was recorded during an HWS test, as can be seen in Fig. 12.6 This plot clearly shows at first that a pressure increase occurs much earlier than a self-heating and at second that the cell goes into thermal runaway even if the safety vent opens and releases gases leading to a pressure drop. Thus, the measurement of the internal pressure could be used to predict the early processes leading to thermal runaway. This method has been adapted from cylindrical to pouch and prismatic automotive cells.

cells with different cathode materials measured at a SOC of 60 %

To collect the gases during the venting of the cell, the abuse tests can be performed inside a gas-tight cylinder that is connected via a small capillary to a Swagelok system with a gas mouse protected by a filter. This filter prevents particles from entering that could damage the delicate GC-MS system. When the cell vents during the abuse test, the gases are collected in the gas mouse. Directly after the test, the gas mouse is brought to the GC system. Then, the gas is released via a gas-feeding system into the inlet of the GC and is analysed both qualitatively and quantitatively using thermal conductivity detectors (TCDs). If unknown components are found, they can be further inspected using a mass spectrometer, which is also combined with the GC system.

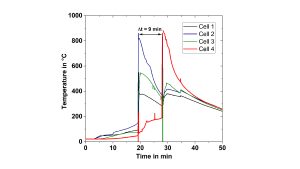

Moreover, the calorimeters allow for studying the thermal runaway propagation in order to develop and qualify suitable countermeasures, such as heat protection barriers. If a thermal runaway is initiated on cells 1-3, the protection material in this example is able to delay the thermal runaway propagation to cell 4 by 9 minutes

(Fig. 13).