The University of Maryland highlights light’s importance in physics, focusing on electromagnetic waves, special relativity, quantum mechanics, and upcoming virtual matter experiments to explore the quantum vacuum’s mysteries.

This is a story about light, matter and light-matter interaction to awaken the quantum vacuum. Most of you reading this article have had encounters with light. Light has been indispensable to life in countless ways, whether it has been feeling the sun’s warmth, peering at stars in the night sky, or sitting around a campfire.

But this story is not about the virtues of light in everyday life; rather, it is about how light has been instrumental in guiding and improving our scientific understanding of the Universe. We will narrow the scope from science in general to physics in particular. We will further hone in on four subjects and their interconnectedness – electromagnetic waves, special relativity, quantum mechanics and virtual matter.

An electromagnetic wave is a fancy way physicists refer to light, because it is a cooperative union of oscillating electric and magnetic fields. Its spectrum ranges from the ultralow-energy radio waves to the extremely high-energy gamma rays. The visible spectrum occupies a tiny sliver in between. Special relativity describes the relationship between space and time and introduces the universal speed limit, the speed with which light travels in a vacuum. Even matter obeys this speed limit.

Quantum mechanics best describes the microscopic world of atoms and molecules. Generally, we do not experience quantum mechanics directly in the macroscopic world of everyday life; however, examples exist. Virtual matter will be the principal character in two forthcoming experiments the physics community is actively preparing to perform in the not-too-distant future and the subject of the last three sections. If you permit me to do so, I will delay defining virtual matter until later in our discussion.

This narrative aims to give you, the reader, a glimpse at how physicists plan to employ light – laser light, extreme laser light – to agitate the quantum vacuum. This will be possible by performing experiments under conditions in the laboratory, which usually can only be found in astrophysical systems.

These environments are responsible for some of the spectacular images the Hubble and James Webb space telescopes obtained. Laboratory-based experiments will enable physicists to address questions nearly a century old and might even shed light on more contemporary puzzles like dark matter.

Along the way, we will review some history that has contributed to the knowledge that enables this pursuit. Throughout our discussion, we will rely on one of the favourite tools of physicists – models – to aid our understanding. So, grab your favourite drink and snack, and join us on this journey.

How light was instrumental in changing the view of matter and radiation

One hundred years ago, the imminent physicist and Nobel Laureate (for his work leading to his discovery of the electron in the late 1800s), Sir JJ Thomson, was credited with stating: ”The study of light has resulted in achievements of insight, imagination and ingenuity unsurpassed in any field of mental activity; it illustrates, too, better than any other branch of physics, the vicissitudes of theories.” His statement is no less true today than it was then. Of course, light goes back to the beginning as we know it. We read in Genesis 1:1, for example: “In the beginning … darkness was over the face of the deep. … And God said, ‘Let there be light,’ and there was light.”

Since the Big Bang, light has been a fundamental tool to effectuate knowledge and create technology. Early on, humans marvelled over lights in the sky, curious about what they were and, in some cases, what they meant. Patterns could be recognised, and ancient communities even built monuments to celebrate daily and annual repeating events.

One could argue that contemporary communities do the same; they call them observatories. The best they could do in centuries past was to work out the celestial mechanics, which is actually quite impressive. But, observing the diversity of spectacular astrophysical events and understanding the physics under the hood driving them had to wait for more powerful instrumentation and scientific revelation.

Back a century again, the needed revelation was afoot – the development of quantum mechanics – which completely changed how physicists viewed the world. This was induced in large measure by the confusing nature of light, sometimes behaving as a wave and sometimes as a particle – corpuscle.¹

In 1704, Issac Newton pushed the idea of the corpuscular nature of light in Opticks. The corpuscle idea was all but abandoned after Thomas Young² demonstrated wave interference about a century later. In the late 1800s, physicists believed that the world was divided neatly into two categories: things were either matter or waves, but not both.

Things began to get complicated moving toward and into the twentieth century with reports of results that had light fitting into the corpuscular categories. A corpuscular nature of light was needed, for example, to explain the photoelectric effect³ and black-body radiation.⁴

Things spiralled further downhill because it was not just light that was exhibiting this disturbing, schizophrenic behaviour; matter was misbehaving as well. Radiation (light) was observed from atoms that were believed to be due to electrons circling the nucleus like planets circle the Sun; this would later become the basis of the Bohr model of the atom. It was well known then that electrons experiencing a force will radiate – give off light. A radiating electron gives up some of its energy. Electrons moving in circles will radiate.⁵

The laser as a precision tool to explore novel quantum physics

Quantum mechanics has led to a very detailed description of the building blocks of the material world – atoms and molecules – and explanations for a variety of phenomena, for example, superconductivity (a macroscopic example of quantum mechanics). Quantum mechanics is responsible for the development of a number of quantum-based technologies. Today, we find ourselves in a second quantum revolution, with quantum being shown virtually everywhere.

In addition to quantum technologies being tools themselves, they have also fueled new research directions, like cooling atoms with lasers, and have enabled additional spin-off technologies. It is fair to say the most well-known quantum device, if not ubiquitous in society, is the laser, which is the protagonist of the rest of our story. By the way, the laser is another macroscopic example of quantum mechanics.

Lasers have come a long way since their inception some 65 years ago. They are the primary tool in investigations ranging from ultrasensitive metrology to ultrafast dynamics and control to preparation of extreme conditions for novel studies.

The last one is the primary driver for what we will now present. Contemporary laser technology allows pulses to be generated on the multi-petawatt level, where 1 petawatt (PW) is equal to 1 billion times 1 million Watts⁹ of power in the form of light. These pulses are packaged to last only a few tens of femtoseconds.

To put this time scale into perspective, 1 fs is to 1 s as 7 ¼ min is to the age of the universe, about 13.8 billion years. The total energy in a 10 PW, 25 fs pulse is about 200 times less than the energy stored in an average cell phone battery today. This seems pretty minuscule.

What is the big deal, you ask? Well, total energy is not the whole story of what we want to discuss below. It is really about how much energy can be delivered to a small spot in a short amount of time. That is the energy per unit time, per unit area – intensity. The quality of pulses that can be generated today is so high that they can be focused to very, very tiny spots. The focal spots can be just a few microns in diameter (about the size of a bacterium).

Concentrating the light of what appears to be a negligible amount of energy can produce intensities so high that it will destroy any material placed in its path. In addition, intensities sufficient to perturb the vacuum are anticipated to be available in the near future. The quantum vacuum is where virtual particles live, which we have yet to define.

From non-relativistic to relativistic quantum mechanics

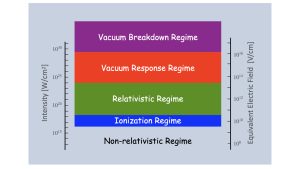

To understand how the vacuum is perturbed by focused laser-light pulses, a bit more background is needed. We begin by considering Fig. 1, which shows how electrons respond in light fields at various intensities. We choose electrons because light interacts primarily with electrons when absorbed by atoms, molecules and solids.

Let me stop for a moment and tell you a little more about light. At the beginning, I mentioned that light is made up of oscillating electric and magnetic fields. Of these, the magnitude of the electric field is stronger than that of the magnetic field by a factor of about 300 million! The interaction between the electron and the electric field is proportional to the strength of the electric field. The interaction between the electron and the magnetic field is proportional to the electron’s speed times the magnetic field strength.

The Schrödinger Equation is generally applied to light absorption in matter in the two lowest regimes in Fig. 1, where electrons move at non-relativistic speeds – i.e., their speeds are much, much less than the speed of light. An important consequence of low speeds is that the force on electrons is due almost exclusively to how the electrons interact with the electric field of the laser. The force due to the magnetic field is almost negligible.10 These two lower regimes are generally the regimes of atomic, molecular and optical physics research where the Schrödinger Equation gives reasonable results.

A transition to the relativistic regime occurs when the electron’s speed is very close to the speed of light, closing the gap of 300 million between the magnitudes of the electric and magnetic forces. Hence, the magnetic force on the electron is no longer negligible. Dynamics induced by the laser must explicitly include both the electric and magnetic forces. There is no specific value that demarks the relativistic speed threshold. One definition often used is when the electron’s speed is about 43% of the speed of light, which corresponds to when the kinetic energy of the electron is equal to its rest-mass energy;11 this threshold is shown in Fig. 1. The magnetic force is odd in that the direction of the force is perpendicular to both the direction of the magnetic field and that of the electron’s motion. The magnetic force can significantly change aspects of light-matter interaction with atoms and molecules.

In the relativistic regime, the equations of motion valid for non-relativistic speeds must be modified for a correct description. The necessary modifications are contained in Einstein’s Theory of Special Relativity. Shortly after the development of the nonrelativistic matter wave equation (Schrödinger Equation), an effort was made to develop a relativistic version of the wave equation. The relativistic version consistent with special relativity that applies to electrons is the Dirac Equation. In addition to being fully relativistic, the Dirac Equation accounts for a fundamental property of electrons that the Schrödinger Equation does not, something called spin. Spin is an internal quantum property of the electron of which there is no classical analogue. While spin can be inserted artificially into the Schrödinger Equation, it is inherent in the Dirac solution.

The Dirac Equation has four solutions – two correspond to the electron’s energy and two to its spin states. The energy in special relativity includes both rest-mass energy and kinetic energy; even a particle that is stationary will have its rest-mass energy.

The odd thing about Dirac’s two energies is that one is negative,12 even for an electron at rest (see Fig. 2). These negative energies were concerning for at least two reasons. First, their interpretation was not clear at first. How, for example, can the rest-mass energy be negative; what does that even mean, physically?

Second, if we accept these negative-energy states, that leads to another problem because they have less energy than all the positive-energy states. In principle, the number of possible negative-energy states is unlimited, as are the number of positive-energies states. Because systems tend to relax to lower energy states when available, it was puzzling why electrons did not relax into the negative energy states.

To solve the second dilemma, Dirac had a brilliant idea; he postulated that all the negative-energy states must be filled with electrons. He called this the negative-energy sea – it is sometimes referred to as simply the Dirac Sea. If all the negative-energy states were filled with electrons, the Pauli Exclusion Principle12 would prevent any other electrons from relaxing into those states.

While the Dirac Sea explains why electrons do not relax into negative-energy states, it does not address how electrons in the Sea should be interpreted. To handle that, Dirac further postulated that because the energies are negative, these electrons must not be observable directly – they must be virtual.

References

1.The corpuscular idea of light dates back to ancient philosophers. Today, we refer to a quanta – a package – of light as a photon.

2.The wave nature was clearly demonstrated in 1801 by light interference leading to bright (constructive interference) and dark (destructive interference) fringes when light passed through two closely spaced narrow slits.

- The removal of electrons from matter depends on the wavelength (energy) and not the intensity.

- Radiation emitted by matter that depends only on its temperature. A correct description fitting the experimental observation is only possible by invoking Planck’s quantised radiation law.

- The only way an electron will move in a circle is if it is experiencing a force. Otherwise, it would move in a straight line according to Mr. Newton’s First Law of Motion.

- It is important to understand that Hamilton’s Principle is just a restatement of Newton’s Laws, albeit more versatile.

- Louis de Broglie had a similar thought and pondered the connection between matter trajectories and the wave nature of matter.

- He gave credit to Born, Jordan and Dirac for developing some of the ideas he used.

- A Watt is a measure of power or energy per unit of time.

- When the electron’s speed is less than 1% of the speed of light, the magnetic force can generally be neglected.

- We have invoked Einstein’s mass-energy equivalence — mass is just a different form of energy.

- Sometimes, an electron bound in an atom is said to have negative energy. In the Dirac case even the rest-mass energy is negative! Rest mass does not appear in the Schrödinger Equation.

- The Pauli Exclusion Principle implies that no two electrons can occupy the same state at the same time.

- A dipole is a bound pair of charges, one being positive (the positron) and the other being negative (the electron).