The race to expand UK offshore wind capacity is running into choppy waters.

A new industry report warns that despite having the world’s largest pipeline of projects, the UK is unlikely to meet its 2030 target of 55 gigawatts (GW).

Bottlenecks in ports, vessels, and supply chains mean only 43 GW is realistically achievable, threatening the country’s position as a global clean energy leader and casting doubt on its net-zero ambitions.

UK offshore wind target at risk

The UK Government has committed to generating 55 GW of offshore wind capacity by 2030, including 5 GW from floating wind.

But according to the EIC’s UK & Europe Offshore Wind report, only 43 GW looks achievable within that timeframe.

Floating wind – seen as crucial for deeper waters – could be particularly constrained, with just 818 megawatts (MW) likely to be in place by 2030.

Despite a vast pipeline of 96.4 GW in development, only seven of the 82 planned projects have reached a final investment decision (FID).

The report cautions that without rapid action on investment, permitting, and port upgrades, Britain risks missing its targets.

Infrastructure bottlenecks hold back progress

At the heart of the challenge is infrastructure. Out of around 80 specialist offshore installation vessels in Europe, just five are capable of handling the next generation of 14–15 MW turbines.

UK projects are competing with continental neighbours for access to these limited assets, creating delays and driving up costs.

Ports also present a major stumbling block. Upgrades typically take six to ten years to move from permitting to full operation.

That timeline is misaligned with UK project deadlines, which means many developments could stall unless capacity is expanded urgently.

The EIC stresses that future Contracts for Difference (CfD) auction rounds – the government’s main subsidy scheme for low-carbon power – will be too late to bridge the gap. Allocation Round 8, scheduled for 2026, will fall outside the 2030 delivery window.

Even the upcoming AR7 round, with results expected in 2025–26, cannot accelerate progress fast enough without parallel investment in ports, grid connections and supply chains.

Looming decommissioning wave adds pressure

The UK’s offshore wind sector also faces the challenge of replacing ageing assets. Several early-generation projects are due for decommissioning from the late 2020s onwards.

Among them is RWE’s Scroby Sands wind farm off Great Yarmouth, scheduled for retirement between 2027 and 2031. Larger sites, such as the London Array with its 175 turbines, are expected to close toward 2038.

These decommissioning projects will compete with new developments for the same limited pool of vessels, ports, and financing, potentially creating a double squeeze on the UK’s offshore wind infrastructure.

European context: Shared challenges

The UK’s difficulties are part of a wider European picture. Across the continent, there is an offshore wind pipeline of 411 GW spanning 386 projects – with floating wind accounting for 37% of future capacity.

Yet 84% of these projects remain in planning or feasibility stages, meaning most new gigawatts will not materialise until after 2030.

Germany, for instance, has 31.1 GW in development but is unlikely to hit its 30-GW 2030 target, with only 21.6 GW expected to be delivered. Auction reforms and ‘negative bidding’ strategies have created price pressures that risk slowing progress further.

France and Norway, by contrast, are pushing ahead with floating wind, with France awarding the world’s first subsidy for a commercial-scale floating project in 2024.

EU policy response

To address these constraints, the European Union has launched several policy measures. The Wind Power Package, Net-Zero Industry Act (NZIA), and Clean Industrial Deal aim to speed up permitting, reform auctions, and expand finance.

Under the NZIA, at least 30% of auctioned capacity must now be awarded on non-price criteria, such as sustainability, supply chain resilience, and job creation.

The European Investment Bank (EIB) is backing these efforts with €6.5bn in guarantees for wind manufacturers and €250m for mid-sized green manufacturers. Major port upgrades are already planned in Esbjerg, Cuxhaven, Cork, and Bilbao to relieve bottlenecks.

Global competition: China pulls ahead

Beyond Europe, global competition adds another layer of pressure. Chinese manufacturers now produce offshore turbines at a scale four times larger than Europe’s capacity – 82 GW annually compared to 20 GW.

With companies such as Mingyang moving into Europe, including a plan to manufacture 18.8 MW turbines in Italy, the report warns of a repeat of the solar industry’s trajectory, where Europe became almost entirely dependent on Chinese imports.

UK’s offshore wind leadership at stake

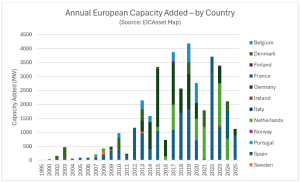

Despite these challenges, the UK remains Europe’s offshore wind leader, with 15.6 GW of operational capacity – well ahead of Germany’s 9 GW and the Netherlands’ 5.5 GW.

Europe as a whole accounts for 43% of global offshore wind capacity, excluding China, with 2.7 GW added last year.

But the EIC warns that unless urgent action is taken to expand port capacity, secure supply chains, and align auction schedules with project timelines, Britain risks losing momentum.

The report concludes that without coordinated investment and political will, the UK could miss its 2030 offshore wind ambitions – undermining its climate goals and its position as a world leader in renewable energy.