Dave Schlossberg, Experimental Physicist at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, explains how scientists at the lab’s National Ignition Facility were able to achieve fusion ignition in 2022, and what this breakthrough meant for their future fusion work.

For over 60 years, scientists from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) in California and their colleagues have been working to achieve one of the most complex and challenging science goals: fusion ignition. In December 2022, the Lab’s dedicated National Ignition Facility (NIF) made history by achieving fusion ignition – producing more fusion energy than the amount of laser energy delivered to the NIF target – for the first time in a lab experiment. This was a major breakthrough in the journey to achieving fusion commercialisation and finding a sustainable, safe, and clean source of energy.

To hear what this colossal milestone meant for LLNL researchers and for fusion research across the globe, as well as achievements at the NIF since, Editor Georgie Purcell sat down with Dave Schlossberg, Experimental Physicist at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

What are your current research focuses and priorities at LLNL?

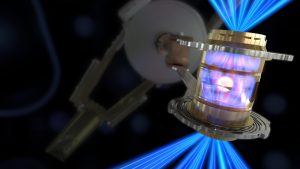

Research into fusion at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory is a large team effort. Specifically, we focus on inertial confinement fusion (ICF) – a type of fusion that uses lasers and the inertia of certain materials to confine very hot gas.

Our team consists of a broad range of scientists, engineers, technicians, and sponsors at a national level. Many priorities and focuses are set by one of our sponsors, the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), and we support stockpile stewardship, national security, and fusion energy.

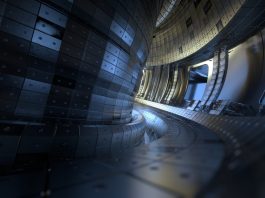

LLNL’s National Ignition Facility, which is focused on the fusion and fusion energy research we do, has three main missions. One is to provide information and support for the stewardship of the US stockpile. The second mission is to perform one-of-a-kind discovery science experiments to better understand how our Universe works. The third mission is to achieve and understand fusion ignition. I also like to say that there is an unofficial fourth mission – to inspire scientists, engineers, and young people to have audacious ideas and bring them to fruition.

Narrowing our work down even further, the ICF programme focuses on producing fusion and controlling plasmas using lasers and the inertia of the material that’s being compressed. The research priorities here are to increase the fusion energy output of our experiments and to develop a deeper understanding of how the physics works so we can make these implosions more efficient.

My individual research is in what I think of as the ‘sweet spot’. It’s great. I lead an experimental portion of these fusion ignition experiments, which entails making hypotheses, testing these hypotheses using the world’s most energetic laser system to create a small star for 100 trillionths of a second, and then analysing the results to see if our hypothesis was confirmed or refuted. So, we uncover a little bit of how the Universe works with each experiment. I also lead a team that builds scientific instrumentation – or diagnostics – to make precise measurements in the extreme conditions of a fusion device. For me, it’s a sweet spot because I get to really test the limits of our physics understanding, and get my hands dirty building hardware and diagnostics that shed new light on aspects of the experiments.

How does your work contribute to the realisation and commercialisation of fusion energy?

We realise and produce fusion at the National Ignition Facility consistently – for more than a decade, we have been routinely carrying out experiments that produce fusion energy. One of the things that makes NIF unique is the type of fusion fuel we use. Many experiments around the world use an isotope of hydrogen called deuterium, whereas we use deuterium and tritium. Our plasma experiments have been using deuterium-tritium for fuel to produce fusion for over 15 years.

Our work contributes to the commercialisation of fusion in several different ways. One exciting new advancement is our institutional initiative for inertial fusion energy (IFE). This is a collaboration with many different organisations – including other national laboratories, universities, academic institutions, and industry partners – to leverage the expertise that we have at LLNL and NIF and bring it to producing fusion energy.

NIF is the only place in the world where we can look at some of the key physics involved in these reactions that you need for a fusion power plant. Some of those are the self-heating of the plasma itself. When you create fusion, some of the particles remain within the plasma and heat it up. Additionally, a fusion energy plant will constantly produce a lot of particles. NIF allows us to investigate damage to materials due to those fast neutrons in our system.

In 2020 and 2021, researchers at the NIF achieved a burning plasma state for the first time in a lab experiment. Why was this such a significant achievement and how was it made possible?

This breakthrough demonstrated that we were on the right track for increasing fusion energy output. You can think of a burning plasma as somewhat like a campfire: when you light a campfire, you’re putting fuel in to get it to light. Once it lights, it starts producing its own energy which sustains the burn. The achievement of the burning plasma state was that first instance of the fire catching. Albeit in this case it was a thermonuclear fire. This was the first indication that we were doing something right by producing a system that can start self-sustaining. From here, we could then look at the physics of how that self-sustainment works and make it even more robust.

© Jason Laurea/LLNL

Researchers around the world have been working on fusion for many years. Often in science, a breakthrough seemingly happens because of a new idea. In reality, this achievement is built on 60 years of research. I believe that continual refinement of the process helped us to reach this point.

In a crucial development, the NIF achieved fusion ignition in 2022. How was this made possible and what role did your work play in this?

One of the main goals of fusion is to confine as much energy as you can inside the region that you want. If you have energy escaping or you don’t put enough energy in, you don’t get to this self-sustaining, burning state. Ignition in 2022 was made possible by making some changes that allowed us to confine more energy in the plasma. In our case, we did this in three key ways. One was to reduce the size of the hole through which the lasers come into the region of interest, because that hole acts like an escape for the heat that we want to confine. Another thing that enabled ignition was to reduce the degradations – the things that drag down the performance, like material mixing into our burning plasma. The third thing was to increase the efficiency of the process, to couple more energy in. In summary, reducing the amount of energy that gets lost and increasing the amount of energy that we put in really pushed us over this edge to reach ignition.

It was a significant breakthrough because it demonstrated to the world that it was possible to achieve more energy out of a fusion reaction than was used to start it. That had never been done before. Since then, we’ve repeated ignition seven times in the laboratory, and we were recently able to achieve ignition using less laser input than we did originally. In fact, one of our most recent ignition experiments used less laser energy to achieve a world-record gain – the amount of fusion energy produced divided by the energy of the laser – a gain larger than four times. That’s a great sign and a pathway that we’re pursuing to make our experiments more efficient.

There’s a fun story attached to my role in this process. My position in NIF spans several areas – I conduct experiments that produce these fusion-ignition plasmas, and I also lead the nuclear diagnostics team, which uses specialised instrumentation to make different measurements within the plasma. Part of my role is to look at the data that comes out of these experiments. The night before the first ignition was achieved, I called the person running the experiment to let them know I was going to bed but to call me if anything interesting happened. At about 2am, I got a call and was asked to look at the data. I logged onto my computer to examine the data and agreed that the findings were a sign that we had achieved ignition. That realisation then started a bit of a race because we wanted to announce this to the world, but we had to be 100% certain that we were correct. During the next seven days, we brought in a panel of experts from the community. We looked at multiple different diagnostics and instrumentation to confirm that we had reached ignition. It was an exciting sprint to evaluate the data and verify this historical event.

What key experiments at LLNL followed this achievement?

At Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and on the National Ignition Facility, the scientists are extremely driven and their ambitions are constantly growing. Very soon after achieving ignition, we were already looking ahead at how to reach the next level. This led to experiments to address such questions as how to make this implosion process more efficient, how to couple more energy in, and how to increase our understanding of what’s happening within these plasmas.

© John Jett and Jake Long/LLNL

Magnetic fusion has a system that runs in steady state for a long time. In contrast, inertial fusion uses a pulsed system where the capsule is compressed and then disassembles to produce energy, and we can repeat this process again and again. One of the key experiments at LLNL was designed to understand what happens as that capsule is disassembling and continuing to produce fusion energy. We’d never done that before, because you need ignition to get to that state where it continues to produce energy as it expands.

What are your goals for the near future?

A large goal for the near future is to continue to increase the fusion energy output that we get from NIF and these implosions. The system’s output performance is incredibly sensitive to small changes in the input parameters. Understanding how we can subtly change these input parameters to increase the energy yield remains a very important aim for the near future.

Another near-term goal is to sustain the facility and the operations that are enabling this cutting-edge physics. The facility was built more than a decade ago, and it was designed two decades ago. Currently, we’ve received funding from our sponsors to sustain the facility to keep it running in tip top shape, to keep enabling production of these amazing world-class plasmas.

The last goal in terms of the near future is to not only sustain the facility, but to enhance it. There’s a proposal for a project that’s passed several levels of government review to enhance the fusion yield capability of the National Ignition Facility by increasing the laser energy and laser power. We’re developing a system that provides more energy to the plasma to drive it harder and produce more fusion energy out.

In terms of the immediate future, tomorrow I’m going back in to work to continue creating fusion implosions and exploring the physics that underlie this fascinating phenomenon.

Please note, this article will also appear in the 22nd edition of our quarterly publication.