Experts at the University of Surrey have developed a pioneering method to uncover hidden structural weaknesses in fusion reactor components.

The method represents a major advance that could be instrumental in building durable, next-generation fusion reactors.

As countries invest heavily in fusion power as a long-term energy solution, understanding how welded materials behave under extreme reactor conditions is proving critical.

Working with the UK Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA), the National Physical Laboratory, and nanoengineering specialists TESCAN, the researchers introduced a novel microscopic imaging approach that reveals vulnerabilities in welded steel joints previously beyond the reach of traditional testing techniques.

Commenting on the breakthrough, Dr Tan Sui, Associate Professor in Materials Engineering at the University of Surrey, said: “Fusion energy has huge potential as a source of clean, reliable energy that could help us to reduce carbon emissions, improve energy security and lower energy costs in the face of rising bills. However, we first need to make sure fusion reactors are safe and built to last.

“Previous studies have looked at material performance at lower temperatures, but we’ve found a way to test how welded joints behave under real fusion reactor conditions, particularly high heat.

“The findings are more representative of harsh fusion environments, making them more useful for future reactor design and safety assessments.”

Cracking the code of welded metals

Fusion reactors operate at extreme temperatures and pressures, and their metal components – particularly welds – must withstand intense thermal stress.

The research team focused on P91 steel, a heat-resistant alloy seen as a promising material for future reactors.

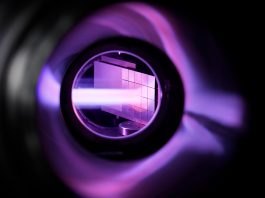

Using a cutting-edge imaging technique known as plasma focused ion beam and digital image correlation (PFIB-DIC), scientists were able to map residual stress in weld zones far narrower than ever previously analysed.

These micro-zones are critical, as stress hidden during manufacturing can compromise performance and drastically shorten a fusion reactor’s operational lifespan.

Heat’s hidden toll on reactor materials

The study revealed that internal stress can have dual effects: enhancing strength in some regions while causing brittleness in others.

At 550°C – the typical operational temperature inside fusion reactors – P91 steel became notably more brittle, with a strength reduction exceeding 30%.

This discovery underlines the importance of accounting for stress behaviour at high temperatures when designing fusion reactor components.

Previous studies focused on lower-temperature environments, but this research directly replicates the extreme conditions inside operational fusion reactors. As a result, it provides more accurate data for assessing material integrity and improving safety.

Powering predictive modelling for fusion energy

Beyond physical testing, the results serve as a vital dataset for refining digital simulation tools, including finite element models and AI-powered predictions.

These technologies are central to fusion projects like the UK’s STEP programme and the EU’s DEMO initiative, which aim to commercialise fusion power in the coming decades.

By improving model accuracy, engineers can better predict material behaviour and lifespan, streamlining reactor design and reducing costly trial-and-error experimentation.

Paving the way for commercial fusion reactors

This breakthrough marks a major step forward in overcoming one of the most technical challenges in fusion energy: material resilience.

The ability to assess welded joints at the microscopic level could redefine safety standards and manufacturing processes across the nuclear sector.

As the world edges closer to realising fusion energy’s promise of low-carbon, virtually limitless power, such innovations are vital.

This pioneering research not only strengthens the foundation for fusion reactors but also accelerates the path toward a cleaner energy future.