A sweeping new study has found that nearly every person in the Netherlands carries PFAS in their blood – and in most cases, at levels higher than what health authorities consider safe.

Conducted by the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), the research highlights widespread exposure to these persistent industrial chemicals, sparking fresh concerns about their long-term effects on human health.

While the presence of PFAS doesn’t mean people will get sick immediately, scientists warn that continued exposure could weaken the immune system and increase vulnerability to various illnesses over time.

What are PFAS, and why are they a concern?

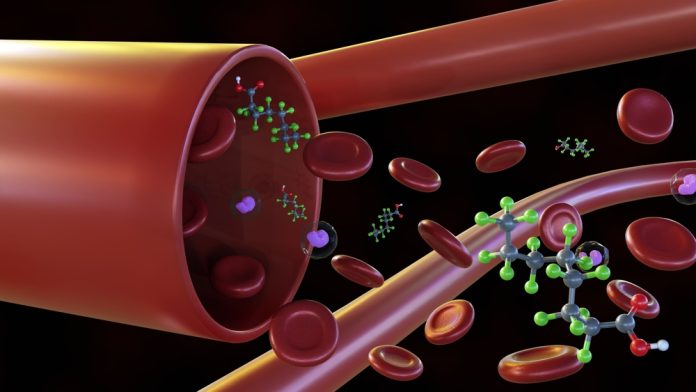

PFAS are a group of human-made chemicals widely used for their water, grease, and stain-resistant properties.

Found in products like non-stick cookware, cosmetics, waterproof clothing, and even food packaging, these substances are notoriously persistent in both the environment and the human body. They are sometimes referred to as ‘forever chemicals’ due to their resistance to breaking down.

While exceeding the health threshold does not mean immediate illness, long-term exposure to high levels of PFAS in blood is associated with a range of potential health issues.

These include weakened immune response, hormonal disruptions, and possibly increased risk of some cancers. The exact effect depends on the amount of PFAS in the body, duration of exposure, and individual health conditions.

Widespread exposure across the Netherlands

The RIVM analysed nearly 1,500 blood samples collected in 2016 and 2017. In almost all samples, researchers found at least seven types of PFAS, with PFOS (perfluorooctanesulfonates) and PFOA (perfluorooctanoic acid) being the most prevalent.

Five of the 28 PFAS compounds studied were not detected in any sample, but the remaining contaminants paint a clear picture of nationwide exposure.

Particular attention was given to regions near known sources of industrial pollution. People living near Dordrecht had significantly higher levels of PFOA, while residents around the Western Scheldt showed elevated PFOS concentrations – both areas are located near factories previously known for PFAS emissions.

How PFAS enter the body and why it’s hard to avoid

The findings align with previous assessments by the RIVM in 2021 and 2023, which estimated that Dutch citizens are ingesting too much PFAS through food and drinking water.

Once absorbed, PFAS accumulate in the body and break down very slowly. Reducing intake is essential to eventually lowering PFAS concentrations below the health limit.

Avoiding PFAS altogether is challenging. These chemicals are present in soil, air, water, and consumer products throughout the country.

Still, experts advise practical steps: eating a varied diet to reduce dietary exposure, and checking product labels for PFAS-related ingredients, especially in non-stick cookware, waterproof clothing, and personal care items.

Government action and future research

To tackle the issue, the Netherlands is collaborating with other European nations on stricter regulations. PFOS has been banned in the EU since 2008, and PFOA followed in 2020.

However, manufacturers have been replacing banned PFAS with newer, unregulated alternatives. To stop this cycle, a European-wide ban on all PFAS has been proposed and is currently under scientific review.

This study is part of a broader PFAS research programme aimed at understanding and minimising public exposure. RIVM plans to analyse more recent blood samples from 2025, with results expected in 2026.

This ongoing surveillance will help measure the effectiveness of policy measures and guide future strategies.

The widespread presence of PFAS in blood across the Netherlands underscores the urgent need for regulatory action and public awareness.

While PFAS exposure may not cause immediate harm, the long-term risks demand sustained efforts from both the government and individuals to minimise contact and protect public health.