The Global Impact Coalition outlines the key considerations for tackling the destruction of PFAS in industrial water systems.

Have you heard of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)? Perhaps the nickname ‘forever chemicals’ rings a bell. These synthetic substances are frequently in the headlines – from the U.S. Administration’s recent $15m investment to study PFAS on US farmland,¹ to their portrayal in the 2019 film Dark Waters, starring Mark Ruffalo as environmental attorney Robert Bilott.² Public concern about PFAS has grown rapidly. To develop viable solutions, we first need to understand the history, use, and impact of these persistent substances.

What are PFAS?

There are many different types of PFAS. According to the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA), PFAS are a group of manmade chemicals characterised by the presence of at least one fully fluorinated methyl (CF3-) or methylene (-CF2-) carbon atom (without any H/Cl/Br/I attached to it).³ PFAS have a wide range of different physical and chemical properties, and come in the form of gases, liquids, or solid high-molecular weight polymers. These PFAS are characterised by a strong carbon-fluorine bond — the most stable bond carbon can form with at least two fluorine molecules attached to the same carbon molecule. It is this extreme stability that gives PFAS their resistance to degradation and their distinctive properties: heat resistance, chemical inertness, and water and grease repellence.

Polymeric PFAS, or fluoropolymers, were first discovered in 1938 by Roy J Plunkett, a young chemist at DuPont, during efforts to develop safer refrigerants.⁴ In the process, he synthesised polytetrafluoroethylene – now widely known as Teflon. This compound belongs to a group of long-chain PFAS, which can include up to 100,000 carbon atoms. To scale up production of Teflon, PFOA (perfluorooctanoic acid), consisting of eight carbon atoms, was used as a processing aid to avoid explosions caused by the chain reaction needed to create Teflon.⁵ Today, the PFAS family includes more than 10,000 compounds, all sharing the resilient carbon-fluorine backbone, but varying in length and functional groups.

All of these have some sort of grease or water-resistant properties and are difficult to break down. Thanks to their non-interactive properties, PFAS are used extensively across sectors – including major industry sectors such as aerospace and defence, automotive, aviation, food, textiles, construction, electronics, and medical. Examples include corrosion-resistant coatings, water-repellent textiles and firefighting foams. Polymeric PFAS (fluoropolymers) are essential materials used in many high-tech applications essential for modern life and where no PFAS substitutes are available today.

Environmental and health consequences

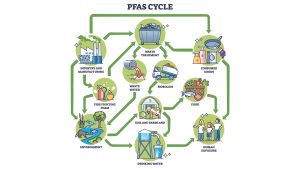

The very stability that makes PFAS commercially valuable also makes them environmentally persistent. PFAS do not break down naturally and some PFAS compounds can travel long distances through air and water. Today, small functionalised PFAS molecules are found in some of the most remote parts of the world,⁶ from Himalayan rainwater to Antarctic snow. Alarmingly, studies have found detectable PFAS levels in the blood of 99% of the global human population.7,8

But presence does not always mean harm. Due to their physical-chemical properties, polymeric PFAS, like Teflon (PTFE) or other fluoropolymers, are not bioavailable, meaning they have limited ability to interact with biological systems and pass through the body without being absorbed. However, small functionalised PFAS molecules, including surfactants and derivatives with similar structures, are more biologically active due to their structural similarity to natural fatty acids. These compounds can accumulate in the body over time and are linked to a range of health problems.9 Wildlife is affected as well. PFAS have been found in species ranging from polar bears to turtles,10 raising serious ecological concerns. As evidence mounts, so does regulatory pressure to address this issue globally.

Industrial consequences

From an industrial standpoint, PFAS present unique challenges, especially in industrial process water. Their resilience makes conventional water treatment processes largely ineffective. Long-chain PFAS (perfluoro carboxylic and perfluoro sulfonic acids with chain length C8-C14, and related compounds), are now more tightly regulated and are somewhat easier to remove. However, short-chain PFAS (perfluoro carboxylic and perfluoro sulfonic acids with C<8) are more mobile, more difficult to eliminate, and are therefore of greater concern for the environment and health. (See Fig. 2)

As PFAS are found in nearly every water stream, industrial facilities using large amounts of process water generally withdrawn from rivers which might be polluted by PFAS derivatives face several risks. Without adequate treatment, PFAS can contaminate products – a serious issue for sectors like food or pharmaceuticals. Infrastructure is also at risk: PFAS can accumulate in pipes, tanks, and waste sludge, complicating safe disposal and management during cleaning campaigns.

However, if PFAS are successfully removed and destroyed at large sites using high quantities of process water, the PFAS levels can drop drastically in proximity to the site. Such a successful solution will likely require a combination of technologies and techniques tailored to a specific location and the composition of wastewater which can vary from one production line to another.11

Finding solutions

Technological innovation is critical. More mature approaches such as advanced filtration (e.g., reverse osmosis, nanofiltration), sorbent materials, and more innovative approaches, including thermal or electrochemical destruction, are all under investigation. However, no single technology currently offers a one-size-fits-all solution, and further research and testing is needed to scale the most promising technologies or to find the most appropriate way to combine existing technologies tailored to local contexts.

Among the most widely used treatment options today are granular activated carbon (GAC), ion exchange resins (IX), and reverse osmosis (RO) or nanofiltration (N).12 GAC is especially effective for removing long-chain PFAS like PFOA and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), while ion exchange resins can target a broader range, including some short-chain compounds. Reverse osmosis and nanofiltration use high-pressure membranes to remove both types effectively, but can be costly and energy intensive. Importantly, these methods isolate PFAS rather than destroy them – raising questions about long-term destruction.

Several emerging destruction technologies, including electrochemical oxidation, cold plasma treatment, or supercritical water treatment, are gaining attention.13 These aim to completely break the carbon–fluorine bonds, thereby mineralising PFAS into byproducts like CO₂, HF, and water. Some early tests show promise, but most remain on the pilot stage and are not yet ready for widespread deployment.

GIC’s PFAS destruction project

Recognising the scale and urgency of the PFAS challenge, the Global Impact Coalition (GIC) is leading a collaborative effort to identify, test, and scale viable PFAS destruction solutions for industrial process water. Through this multi-partner project, GIC aims to co-study the performance of different technologies, co-develop tailored industrial solutions, and co-pilot those solutions at operational sites.

The focus is on tackling short-chain PFAS, which are both more mobile and more difficult to eliminate. Using shared infrastructure and expertise from GIC members, the project aims to test technologies at real-world industrial sites. The goal is to generate actionable insights and accelerate progress toward safe, scalable, and cost-effective PFAS treatment systems.

By combining technical knowledge, industry access, and global collaboration, GIC is helping bridge the current knowledge gap – and working to address the global PFAS challenge.

Calling innovators

Are you working on a technology for destroying short-chain PFAS in water? We’re interested to find out more! Reach out to connect with the Global Impact Coalition Innovation Ecosystem.

References

- Tom Perkings. Trump administration yanks 15m dollar in research into pfas on us farms: not just stupid, it’s evil. The Guardian, 2025 July 11.

- Lauren Collee. Dark waters: unsung Todd Haynes legal drama is a master class in dread. The Guardian, 2024 February 20.

- EHCA, European Chemicals Agency, Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) overview (Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) – ECHA)

- R.B. Seymour and G.S. Kershenbaum. Plunkett, r.j. “The history of poly tetrafluoroethylene: Discovery and development,” high performance polymers: Their origin and development. proceedings of the symposium on the history of high performance polymers at the American Chemical Society meeting, New York, April 15-18 1986. New York: Elsevier, 1986.

- Rudy Molinek. The long, strange history of Teflon, the indestructible product nothing seems to stick to. Smithsonian Magazine, August 20, 2024.

- Sharon Guynup. Pfas ‘forever chemicals’ harming wildlife the world over: Study. Mongabay, 26 September, 2023.

- HBM4EU. Policy brief pfas. European Human Biomonitoring Initiative, JUNE 2022.

- Kuklenyik Z, Reidy JA, Needham LL., Calafat AM and Wong LY. “Polyfluoroalkyl chemicals in the U.S. population: data from the national health and nutrition examination survey (N.Hanes) 2003-2004 and comparisons with N.Hanes 1999-2000. Environ Health Perspect, 2007 Nov.

- Boobis A, DeWitt JC, Lau C Ng C, Smith JS and Roberts SM. Fenton SE, Ducatman A. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance toxicity and human health review: Current state of knowledge and strategies for informing future research. Environ Toxicol Chem., March 2021.

- Environmental Working Group. Wildlife around the world. Forever chemicals’ found in, SEPTEMBER26, 2023.

- Pradeep Shukla Jim Fenstermacher and Prashant Srivastava. Unravelling PFAS challenges and advances in contaminant remediation. The Chemical Engineer, February 27, 2025.

- EPA factsheet: Treatment Options for Removing PFAS from Drinking Water April 2024

- Sona Dadhania, IDTechEX, Emerging PFAS destruction technologies, Water Industry Journal; 2025

Please note, this article will also appear in the 23rd edition of our quarterly publication.