From permeable adsorption barriers to phytoremediation: Upstream passive interventions can address PFAS plumes with minimal O&M, reducing lifecycle risk and cost for utilities, regulators and asset owners.

PFAS contamination is one of the most persistent environmental challenges of our time. Treating PFAS-impacted water at water treatment plants or at the point of entry or use in homes and businesses, or providing an alternate water supply, can help manage risk in certain scenarios. However, it does not tackle the continuous flow of PFAS from source areas.

There is growing recognition, driven by two factors, that controlling PFAS at the source (upstream) can be more effective and sustainable than relying solely on downstream strategies.

First, PFAS action levels are extremely low (parts per trillion or even quadrillion), which makes both treatment and proving treatment performance costly and complex. Analysing samples often takes weeks, which consumers struggle to accept for something as essential as drinking water.

Second, treating only at the receptors can lock owners into decades of spending.

In contrast, targeting efforts on upstream source control can sustainably and cost-effectively lower mass flux (i.e., the rate at which substances such as PFAS move through a defined area over time) before they enter the broader catchment.

Source identification

In complex sites – such as industrial or urban catchments – fingerprinting using machine learning techniques can efficiently evaluate and classify hundreds of chemical compounds or data signatures. These methods help differentiate contaminants originating from a specific site (‘site-derived’) from those present in the surrounding environment (‘ambient’). This approach is especially valuable in supporting the ‘polluter pays’ principle, ensuring that regulatory actions and clean-up efforts are focused where they are most needed, and not confounded by background contamination.

Conventional pump-and-treat systems for PFAS are well established, but once they have been turned on, they are hard to turn off – even after apparent goal attainment – because regulators are understandably reluctant to allow shutdowns. When used to achieve low-level PFAS treatment goals in groundwater, these systems will likely operate for decades to address point sources and could have to deal with the added complexity of potential background or ‘ambient’ sources of PFAS contamination. Additionally, pump-and-treat systems that do not include a PFAS destruction mechanism transfer PFAS impacts from groundwater to a treatment media (e.g., granular activated carbon or ion exchange resins). The treatment media becomes a secondary waste stream that must be managed. Conversely, passive treatment systems have been gaining more consideration because of their typically lower carbon footprint, reduced operation and maintenance requirements, and, in some cases, limited to no generation of a secondary waste stream requiring additional treatment. By achieving PFAS flux reduction, passive source treatment can help reduce treatment pressure downstream while supporting wider water security aims.

Passive toolkit in practice

Passive approaches leverage hydraulic gradients and typically involve a permeable barrier containing a sorbent media, which captures PFAS (by adsorption and/or absorption) as ground or surface water passes through it.

- Permeable sorption/adsorption barriers (PSBs/PABs) are constructed subsurface to treat groundwater. The sorption media is applied via trenching in soil mixing or in removable ‘gates’ or can be directly injected into the aquifer. When the PFAS sorption capacity of the media has been reached, the media can be replaced or replenished. Treatment train approaches, such as the addition of phyto-remediation components and/or food-grade polymer injections, may be used to address co-contaminants, short-chain PFAS or water quality issues to extend the lifecycle of the sorption media.

Barriers can be installed vertically or horizontally:

- Funnel and gate geometries involve an impermeable funnel that guides contaminated groundwater to a gate comprising a permeable, replaceable media-filled section. This media-filled section does the ‘work’ to remove PFAS from the groundwater flux.

- Lateral barriers involve horizontal layers of media mixed in and below PFAS-impacted soil or fill to intercept infiltration and protect groundwater and/or reduce PFAS uptake by plants. This enables the beneficial reuse of large soil volumes on-site.

- Modular passive gates are used to intercept PFAS contamination in surface water, for example, across streams, ditches or creeks. These gates are made of replaceable gabion baskets or similar filled with sorbent media. The gates can be sequenced – e.g., a prefilter for suspended solids followed by PFAS media – to ensure flow passes unimpeded and maximises the life of the media. They are best suited to low-energy flow environments to avoid backing up water or destabilising banks. A bypass must be included to manage storm or snowmelt peaks.

The feasibility of these systems is judged on annual mass captured versus cost, not on treating the absolute peak flow. For higher flow scenarios where gabion concepts become impractical, a multi-chamber concrete vault system filled with sorbent can deliver the same low-energy principle at scale.

Sorbent media

A range of different media and media mixes have been successfully trialled as sorbents, including powdered or colloidal activated carbon, granular activated carbon, biochar, modified organoclays, mineral blends, pulverised carbon ash and many others. These can be mixed with site soils or other granular materials to maintain permeability in layered designs. The choice and loading of the sorbent, i.e. the amount of PFAS it can capture, will tie back to mass flux, the desired design life, and its constructability.

Phytoremediation: PEIR BarrierTM

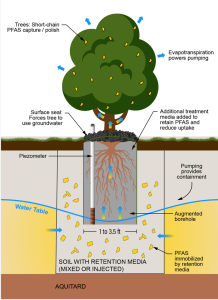

In addition to the passive, sorption-based barriers outlined above, WSP has been exploring how the natural processes of trees and other plants can be harnessed to form a Phyto Enhanced In-situ Remediation (PEIR) Barrier.

Phytoremediation involves adding a nature-based treatment component to address PFAS. By planting trees over a passive barrier, a nature-based ‘pump’ is added to the treatment system, making the remedy ‘active’ at low energy, cost and maintenance. Trees draw groundwater towards their root zones – the rhizosphere – where added carbon and microbial allies (which boost plant resilience by lowering groundwater and soil pH) provide extra PFAS retention, to improve overall capture and sorption capacity. This action is particularly beneficial in helping control short- and ultrashort-chain PFAS, for which many sorption media are less effective at capturing. By supporting transfer of short- and ultrashort-chain PFAS from groundwater to the rhizosphere, the sorption media applied to address PFAS in groundwater have added capacity to further reduce long-chain PFAS concentrations.

Phytoremediation as part of a PEIR Barrier is appropriate for sites with plant-tolerable soils and shallow groundwater (less than 7m/25 ft). Tree species are selected based on their water usage and ecological ‘fit’ to the site. Common species selected for specific locations based on their hydraulic uptake include willows and poplars.

Plants, such as grasses, sedges and rushes, can also perform the same function in small engineered, riparian wetlands and can be similarly helpful in terms of capturing short-chain PFAS. The use of alternative plants is assessed based on treatment goals. When added to lateral barriers, grasses, sedges, and rushes can be used to address PFAS in surface water or to control PFAS gradients in pore water to minimise the potential leaching of PFAS to groundwater.

The hybrid play

In some instances, the PFAS flux may be too high for passive systems alone. Targeted active treatment methods (e.g., pump-and-treat or foam fractionation using destructive, separation or sorption technologies) specifically designed for pre-determined, limited duration applications can lower source zone mass where needed to allow passive barriers to then manage low contaminant flux with low energy use and minimal O&M. This approach extends sorption media life and reduces replacement frequency.

Down gradient, Monitored Natural Retention (MNR), which involves documenting the stability of the PFAS plume due to natural geochemical or hydraulic conditions, may be defensible if residual concentrations are low enough. WSP’s Groundwater Plume Analytics tools, which evaluate contaminant movement in groundwater by analysing whole plume stability, can help support MNR strategies throughout the treatment process/life cycle.

Designing with passive solutions: What decision makers need to know

When considering passive upstream solutions for PFAS, concentration alone is a poor guide. What matters most is the mass of PFAS moving through pathways (i.e., the flux). A thorough understanding of site conditions over time should include:

- Hydrogeology and hydrology: Barriers only work if PFAS-bearing water makes contact with the sorbent for a sufficient time. It is vital to identify preferential pathways or potential remedy bypass pathways. Prioritising pathways carrying the most PFAS mass is central to cost-effective designs and solutions.

- PFAS composition and geochemistry: Adsorption efficiency varies with PFAS chain length and water chemistry. Contact time can be increased by making barriers thicker. Consider phytoremediation where short chains matter or other factors limit the use of thicker barriers.

- Co-contaminants: Hydrocarbons and other organics can bind more readily to sorbent media than PFAS. Media formulations and barrier thickness must be adapted accordingly. In some instances, additional treatments to address co-contaminants (including a phytoremediation component) can improve PFAS treatment efficiency and performance lifecycle.

- Flow variability: Passive systems must be sized for typical throughputs and include bypasses for peak flows, particularly in surface water applications.

- PFAS concentrations: Very high PFAS flux can overwhelm media capacity. Traditional treatment methods may be required initially. Nonetheless, implementing a traditional treatment approach without including a plan for transitioning to a more passive treatment system in the future may result in a longer-than-necessary traditional treatment system operational life cycle and costs.

- Regulatory stance: Different geographies may favour different systems. Some regulators prefer shallower, trench-type or lateral capture systems over injections that hold PFAS mass within aquifers.

Upstream, low-energy passive controls are not simply ‘nice to haves’ – they are a cost control strategy for the entire system. By cutting PFAS flux at the source, pairing sorption barriers with phytoremediation where feasible, and hybridising when flux is extreme, owners and regulators can manage risk effectively.

Case studies

Australia

WSP partnered with a major Australian airport to deliver a solution for managing and reusing 1,000,000m³ of low-level, PFAS-contaminated soil. WSP designed a permeable sorption barrier that enabled safe in situ reuse of untreated soils above a purpose-built sorptive layer. The flexible design accommodated various media and mixing methods. Over two years of monitoring have indicated no net increase in PFAS load beneath the surcharge. The design delivered $23m in cost savings while reducing landfill use and carbon emissions.

North America

WSP implemented a Phyto Enhanced In-situ Remediation (PEIR) Barrier at a former industrial site in Michigan, where suspected aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF) releases had led to groundwater contamination. WSP combined biochar injection, native tree planting, and beneficial microbes to create a resilient, multi-layered treatment zone. Concentrations of PFOS (a type of PFAS) were lowered from 3,190 ng/L to 2–7 ng/L over three years, with no rebound observed. The cost savings of the PEIR Barrier compared to a traditional pump-and-treat approach (assuming a 30-year life cycle) were estimated to be between 60% and 70%.