Marco Calviani, STI Group Deputy Head, Systems Department, Targets, Collimators and Dumps Section Leader at CERN, discusses the work of the team and the unique challenges they encounter in maintaining reliability and durability.

AT CERN, the management and maintenance of beam-intercepting devices are crucial for ensuring both the safety and efficiency of the accelerator complex. This dedicated team collaborates closely with various teams across CERN, focusing on the entire lifecycle of these devices to develop innovative solutions.

To learn more, The Innovation Platform’s Maddie Hall spoke with Marco Calviani about the work of the team, its importance for high-energy physics experiments and the unique challenges.

Importance and functions of beam interception at CERN: Ensuring safety and efficiency in the accelerator complex

A beam-intercepting device intercepts accelerated particle beams. This can be done for three main purposes: to produce particles, to protect sensitive equipment, and to safely dispose of particles produced during experiments. As part of a collaborative effort with a variety of teams at CERN, our team specialises in the entire lifecycle management of beam intercepting devices, overseeing all aspects, in collaboration with other CERN groups, from initial design, to construction, installation, operation, maintenance and waste packaging.

Targets

One aspect of our work is the development of targets that produce secondary pions, muons, kaons, electrons, neutrons and all species that can be used by fixed target experiments. While neutrons are sometimes considered unwanted byproducts, they play a critical role at the n_TOF facility, where they are used for experiments in nuclear physics. In other instances, neutrons (as well as in high energy hadrons) can be problematic, as they cause the radioactivation of components, especially when they are thermalised. Additionally, neutrons can pose issues for electronics; for example, they can cause bit flips in sensitive electronic components, impacting the acquisition systems and equipment controls.

Neutrons are uncharged particles, which means we cannot bend their trajectory like we can with charged particles. Instead, we guide thermal and sub-thermal neutrons through beam guides. Cold neutrons can be directed using special mirrors, but in the case of the neutron Time-of-Flight (n_TOF) experiments, dealing with neutrons, from high energy to thermal ones, the only option is to shape the beam reaching the experimental areas by means of specialised collimators and absorbers. Our team is responsible for both the neutron-producing target and the primary beam lines that guide neutrons toward experiments.

Collimators

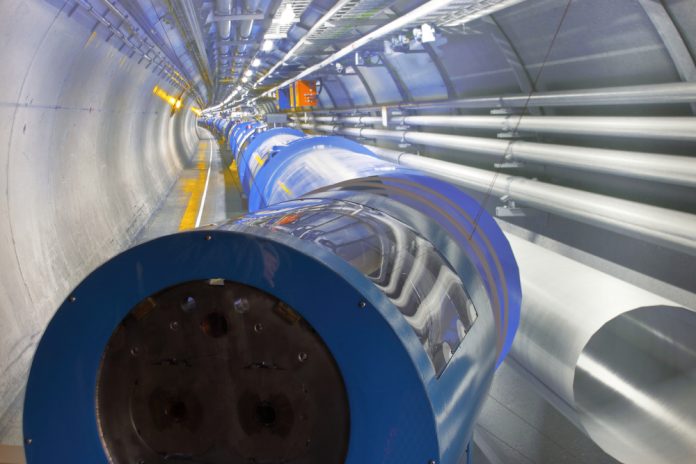

Secondly, our team is involved in the production, operation and maintenance of beam collimators, typically employed to protect sensitive equipment that cannot tolerate direct impact from the primary beam, as well as to clean the halo of the circulating proton beams. For example, in the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), we use more than 100 collimators distributed in the entire machine to safeguard superconducting magnets from damage, as well as to protect sensitive equipment in LHC experiment, such as silicon detectors.

Beam dump

A specific type of beam intercepting device are beam dumps, which are generally the only equipment capable of absorbing the full energy and power of the beams we work with. For instance, the LHC beam dump, which must absorb between 500 and up to 700 Megajoules (MJ) in the high luminosity LHC era, all deposited in just 90 microseconds.

The full LHC beam can only be directed here; sending it elsewhere would cause it to create massive damage in the vacuum chamber and magnets, leading to failures. Additionally, the systems involved must be extremely reliable, as they serve both machine and personnel protection purposes. For instance, in the injector complex, we have mechanical objects that need to reliably block the beam passage to allow safe intervention in downstream areas. In any unsafe events, the beam would strike the absorbing part of these components, preventing any dangerous situations for personnel who need to intervene in the beam and experimental facilities. Everything must function very reliably (and we have redundancy) and be able to withstand and resist the intensity of the beams.

The Beam Dump Facility (BDF), or HI-ECN3 project, is a CERN project designed for high-intensity beam dumps and fixed-target experiments, initially focusing on the Search for Hidden Particles (SHiP) experiment to investigate light dark matter and hidden sector particles. Our teams are introducing a new high-power target for the experiment, capable of absorbing up to 350 kW and a peak energy of 2.6 MJ in 1 second. It will be helium-cooled and constructed primarily of pure tungsten absorber, measuring almost 1.5 m in length and about 30 cm in diameter. Although this target is primarily optimised to produce charm mesons rather than for neutron production, the high-energy proton beam (400 GeV), coupled with the high average beam power, will generate significant neutron byproducts. There is potential interest from the physics community to utilise some of these neutrons for worldwide, unique research in nuclear astrophysics.

Ensuring durability and reliability

Generally, our design begins with a clear definition of functional specification, followed by an early conceptual design, coupled by simulations to evaluate the effects of the interactions between particle beams and matter. These interactions generally generate radiation and heat and are simulated by Monte Carlo codes such as FLUKA.Thermal and stress behaviour assessment follows, which helps address material choices and behaviour, structural considerations, etc. as well as cooling, if required. Then we always take into account radiation protection aspects, for operation and maintenance, as most of our components generally become radioactive during use. As part of our quality assurance procedure, we aim at validating our predictions through real-world testing of components and systems at CERN or collaborating institutes. All these steps include collaborative effort that leverages the expertise of various groups within CERN.

We conduct offline experimental testing and validation using mock-ups, as well as beam testing, to replicate accelerator conditions and ensure that our systems perform as expected. With access to testing equipment and infrastructures both here at CERN and facilities worldwide, we can validate our simulations effectively and ensure that the technology employed allows us to reply effectively to the functional specifications.

Collaboration is also crucial. We engage with labs worldwide, exchanging ideas and learning from each other’s experiences and mistakes, fostering continuous improvement.

Significant challenges in engineering neutron beams or sources and the impact of HL-LHC development

The design of our components presents varying levels of challenges, depending on the specific component in question.

Due to the beam energy deposition, one of our primary challenges is to effectively manage heat removal from these components, which is particularly complex when working in ultra-high vacuum environments. In recent years, we have concentrated on enhancing the R&D on our heat removal techniques, with a focus on diffusion bonding via hot isostatic pressing. This method enables us to join dissimilar materials while optimising heat dissipation. Moreover, a significant challenge is the thermomechanical stresses in induced by temperature gradients, which can impact component robustness. When a small beam strikes a larger object, only a small area heats up, generating internal pressure as the hot material expands while the surrounding material does not. This results in tensile and compressive stresses, pushing materials to their limits. Sometimes it is not possible to reliably simulate the material due to the extreme regimes, necessitating experimental validation.

Nitrogen leak

Up to 2018, a larger volume of the LHC beam dump was filled with nitrogen to prevent the oxidation of the graphite, which serves as the absorbing component of the dump. However, during the course of LHC Run1, we started experiencing nitrogen leaks from the system. Initial investigations failed to identify the physical origin of these leaks, prompting us to implement several measures to maintain the nitrogen levels.

The energy absorbed by the beam in the dump’s graphite was exceptionally high. The asymmetric distribution of energy in the dump stainless steel vessel is causing the entire structure to vibrate, akin to a bell. This device weighs 6.5 tonnes and was shaking at a main frequency of 120 Hz, creating forces upward of 200g and point-to-point vibrations of up to one centimetre at every dump event. Our top priority was to ensure safe operating conditions, necessitating interventions to fix the leak and prevent graphite oxidation. It was clear that a major system upgrade was essential, and that’s exactly what we implemented during LS2. The upgrade consisted in modifying the spare dumps and placing them on two highly performing steel ropes, which allowed the dump to move and vibrate after each dump without affecting the neighboring structures.

Moreover, an inspection using an endoscope found that a portion of the graphite absorbing material located in the middle of the core was damaged; this location was challenging to access due to its radioactive nature and the dump’s size.

Lessons learned for future projects

Regarding the High Luminosity LHC (HL-LHC) project, our team has several developments to address in the coming years. We are currently in the production phase, focusing on the manufacture of about 50 new collimators and masks – some of them of a brand new design to match the requirements and challenges of HL-LHC – and three new beam dumps, these ones employing new materials, such as advanced carbon-carbon fibres for the absorbing part and titanium alloys for the containing vessel. As we transition into the ramp-up phase, we will systematically construct, test, and install a range of components, while simultaneously decommissioning older ones.

One challenge we’ve encountered so far is with the beam dump design for HL-LHC, where we will need to handle about 30% more energy than we had previously during Run3. Our team is currently investigating different materials for the new dump. While up to now, we’ve been using a specific grade of stainless steel, we’re planning to switch to titanium—specifically, titanium grade 5. This alloy is lighter and has a lower density, which should help reduce the overall dump vibrations. We’re confident that this change will allow us to safely absorb the additional energy generated by the High-Luminosity beams.

Advanced engineering techniques for the n_TOF facility

The research and development we undertake in beam-intercepting systems play a pivotal role in meeting the demands of the high-energy physics and nuclear physics communities. Each area of physics brings its own set of challenges, pushing us to develop specialised technologies, materials, and techniques.

The n_TOF facility has been operational for almost 25 years, and during this period, it has undergone several improvements and upgrades. This meant taking some calculated risks by using technology that hadn’t been tested before to meet the experimental requirements.

Most recently, in 2021, we began operating the third-generation Spallation target. This new target is significantly different from its predecessor, being nitrogen-gas-cooled, consisting of slabs of solid highly pure lead with gas flowing through it for cooling. The target is impacted by a proton beam of 20 GeV/c. The beam is very focused and short, lasting only about seven nanoseconds, with an intensity of up to 10^13 protons per pulse every few seconds. In this facility, neutrons produced by the target are reaching the experimental stations with energies spanning almost 11 orders of magnitude, aiming to create unique measurements characterised by high neutron energy resolution.

Implementing the LHC Injectors Upgrade (LIU) project: Challenges and lessons learned

The LIU was a key project conducted during Long Shutdown 2, during which the entire injector chain was prepared to deliver the high-brightness beams required for HL-LHC. Throughout the LIU project, we faced several challenges due to the challenging requirements of the project, particularly in developing hardware systems for the accelerators. A notable example was during the design and construction of the new SPS beam dump. The Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS) is the last stage in the injector chain for CERN’s Large Hadron Collider, as well as the workhorse for high-intensity fixed target physics in CERN’s North Area. During Long Shutdown 2, we set about installing a new beam dump in one of the long straight sections of the SPS. The new beam dump, which has been in operation since May 2021, has an optimised design to handle proton beams with a momentum spectrum of 14 to 450 GeV/c and the capability to absorb protons with a maximum average power of up to ~270 kW. Monte Carlo simulations using the FLUKA code were conducted to assess energy density distribution in the dump, followed by thermomechanical analyses in FEA and CFD simulations to evaluate heat transfer from the absorbing core to the heat sink and evaluate the robustness of the absorbing materials, as well as of the overall system.

The key technical challenges faced included managing high thermal energy and radiation levels through extensive thermomechanical finite-element simulations and the application of hot isostatic pressing techniques for improved thermal conductivity.

Our goal was to ensure we met the functional specifications necessary to handle increased beam power and beam brilliance. To achieve this, we partnered with industry leaders and research institutions to implement diffusion bonding via advanced isostatic pressing technology. This innovation allowed us to perform diffusion bonding between dissimilar materials, specifically bonding copper alloys acting as heat sinks with stainless steel, where water circulates to remove the heat.

Having now mastered this technology, we can apply it more broadly to various beam-intercepting devices. The aforementioned HI-ECN3 project, for instance, is benefiting from these advancements, as we are now diffusion bonding also refractory metals, including molybdenum, tantalum, niobium and tungsten. Although the materials we use may differ, the underlying technology and concepts remain consistent, enabling us to reap the rewards of our upgraded techniques across a wide range of components.

Through internal collaboration at CERN, engaging various teams, including transport, robotics, and radiation protection specialists, it was decided to accelerate the dismantling and post-irradiation examination of the removed LHC beam dump to ensure the safe operation of future devices. Our teams constructed a bunker dedicated to cutting these components using an array of techniques, including a remotely operated saw as well as robotic assistance. This approach allowed us to successfully cut the dump, identify the failing part, and incorporate this information back into our simulation package to better understand the cause of the failure and upgrade the dumps in the context of the LHC Run3 as well as for the HL-LHC project.

During the operation of high-energy accelerators, the interaction of radiation with matter can lead to the activation of machine components and of the surrounding infrastructure. Radioactive waste (RW) produced during maintenance operations and the decommissioning of an installation must be managed and disposed of in accordance with the regulatory framework defined with the Host States. RW produced at CERN is then disposed of either in France or Switzerland, depending on its classification.

Learning from LS2

Both the good and bad experiences are implemented and then reinjected in the design of our components, drawing from not only our insights but also those of the entire organisation and various laboratories globally with which we collaborate and share experiences.

In addition to our HL-LHC deliverables and HI-ECN3 mentioned earlier, our team are engaged in several key CERN projects:

- North Area Consolidation Project: This initiative focuses on designing and upgrading components to guarantee the long-term operability of the North Area experimental hall

- ISOLDE Facility: With the recent funding received for implementing an improvement, we are conducting multiple upgrades, including the exchange of two beam dumps to accommodate the higher intensity provided by the PS Booster.

- AWAKE Facility: We are working on extending the plasma wakefield acceleration facility’s capabilities by dismantling the old target area of the CNGS facility, which produced neutrinos towards the Gran Sasso facility in Italy. Rather than constructing new experimental facilities, the project’s aim is to repurpose existing ones that are no longer in use for sustainability and cost efficiency. Our team plays a crucial role in the nuclear dismantling aspect of this project, which involves the careful removal of all radioactive components and clean-up.

Developing the Future Circular Collider (FCC)

The FCC is a proposed high-performance particle accelerator that could succeed the LHC once it has concluded its High-Luminosity phase. Currently, we are focused on developing a pre-technical design report for the beam-intercepting devices that will be necessary for the FCC, pending project approval. Our initial assessments have identified many more components than we anticipated, and our scope is extensive across the new complex throughout the injector complex, booster and collider. We will need to construct hundreds of devices, ranging from conventional systems to more innovative designs that are still in the conceptual phase. Some of the equipment will draw inspiration and lessons learnt from the technologies utilised in the LHC, particularly in the design of collimators. Consistent with the LHC and similar projects, the FCC design will incorporate numerous collimators. Our starting point is the positron source, which will be a refractory metal target, likely pure tungsten. In this setup, electrons will collide with a cooled tungsten block to produce positrons.

However, there are several specialised devices planned for the FCC that differ from those at the LHC. At each interaction point in the FCC electron-positron machine, we will feature a unique physics aspect known as the beamstrahlung effect, which involves the production of two photon beams to the left and right of each interaction point. These high-power photon beams will be capable of reaching energies up to hundreds of MeV, each one carrying up to 500 kW of power, a distinguishing characteristic no facilities possess to date, owing to the energy and intensity of the lepton beams.

Ensuring the safe absorption of these photons is crucial. Unlike protons and electrons, photons are electrically neutral and travel without any means of deflection. In our current infrastructure design, we anticipate a separation of approximately 1.5 to 2m between the lepton beams and the photon beams at 500 meters from the interaction points. At this location, we will place an absorber to safely absorb the high-energy photons (and potentially use it for other purposes – see Other Science Opportunities at the FCC-ee).

We are actively investigating how to manage the unique properties of high-energy and high-intensity photons concerning their interaction with matter. Unlike protons, which can penetrate deeply into materials at high energy, photons have a much shorter interaction range. Even at elevated intensities, a significant number of photons may penetrate only 20 to 50 cm into an absorber, depending on its density. This limitation results in very high energy densities concentrated in localised areas.

To handle these high energy densities, in the framework of a collaboration with member state institutes, we are considering an absorber made of liquid lead, due to the unique effective capacity of absorbing photons (it is a common choice for shielding in various applications, such as dental X-rays). The challenge lies in maintaining liquid lead in a molten state, which necessitates a circulation system to enable effective absorption of the photon beams, keeping it reliable for long periods and handling the varying levels of beam power. Therefore, while we are exploring multiple options, the liquid lead system currently stands out due to its unique requirements and effectiveness – and we have plans of realising a prototype to demonstrate these capabilities.

Please note, this article will also appear in the 24th edition of our quarterly publication.