Chalmers University of Technology discusses the importance of a closed nuclear fuel cycle in enhancing sustainability by recycling spent nuclear fuel, allowing for more efficient use of uranium and improved waste management.

As the global energy system moves toward low-carbon solutions, nuclear power plants continue to play a role by delivering large-scale, reliable electricity with minimal operational carbon emissions. In Sweden, nuclear energy has long been a key component of the electricity system, accounting for about 30% of total electricity production in 2024. Globally, nuclear power contributed approximately 9% to electricity generation that same year.¹

A promising development for Sweden’s energy future is small modular reactors (SMRs), supported by the ANItA initiative, which links academia and industry to provide knowledge-based decision support. This article explores key questions on the closed nuclear fuel cycle, aligning with Anita’s vision.²

What is spent nuclear fuel?

During nuclear reactor operation, fuel produces energy while building up fission products and heavier elements like plutonium. The time fuel spends inside the reactor, called residence time, varies depending on reactor type, fuel design, and burnup targets. Typically, fuel remains in the core for three to five years before being discharged. At this point, the used fuel is highly radioactive and still generating a lot of heat, so it must be stored under water in spent-fuel pools for roughly five to ten years to allow it to cool. After cooling, before preparing for recycling, the fuel is cut into pieces and dissolved in nitric acid.

Most of the spent nuclear fuel is still uranium, with a smaller but important fraction of new elements formed due to irradiation in the reactor. For a typical spent uranium-oxide (UOX) fuel, the composition is roughly ~94% uranium (mostly the isotope U-238), about ~1% plutonium formed from neutron capture in Uranium nuclei, ~0.2-0.3% minor actinides such as neptunium, americium, and curium, and around ~4-5% fission products.³

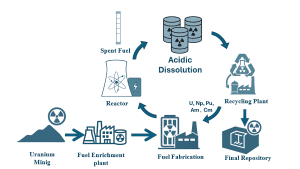

What is a closed nuclear fuel cycle?

The main concept of closed fuel cycles is that the used fuel is not treated as waste. Instead, it is considered a valuable resource. Through reprocessing, actinides like uranium, plutonium, neptunium, americium, and curium can be recycled and made available for future nuclear fuel fabrication.

This contrasts with the open (once-through) fuel cycle, in which spent nuclear fuel is cooled, stored, and lastly disposed of in a deep geological repository, where it must remain safely isolated for hundreds of thousands of years.

Closing the fuel cycle offers more sustainable use of nuclear resources and a smarter long-term waste strategy. Reprocessing helps us to use the uranium we have already mined more efficiently and allows us to extract more value from mined uranium by recovering and recycling usable materials. It can also improve waste management, where, if long-lived actinides are separated and recycled, the waste you eventually send to a repository is mostly fission products. Those decay much faster than the transuranic elements present in nuclear fuel, so the waste doesn’t stay as radiotoxic and heat-producing for nearly as long.

What technologies make the closed fuel cycle possible?

In recent years, there’s been increasing interest in developing more advanced partitioning processes, using either hydrometallurgical approaches, such as solvent extraction, or high-temperature pyrometallurgical techniques.

Reprocessing and solvent extraction

One of the key technologies that aims to close the nuclear fuel cycle is aqueous reprocessing.

The idea is simple in principle: dissolve the used fuel in nitric acid and then use solvent extraction to selectively pull out the metals we want to reuse.

Solvent extraction, also known as liquid-liquid extraction, is a widely used separation technique. It relies on the difference in solubility of a solute between two immiscible phases, commonly an organic phase and an aqueous phase, to achieve separation.

It is based on the selective extraction of desired metals from the aqueous phase to the organic phase. Later, those metals can be back-extracted into a clean aqueous stream for further processing or fuel fabrication.

The effectiveness of this system depends on several parameters, such as the type of extractant, acidity, temperature, and how the liquids are mixed and separated. Chemistry can be elegant, but making it work reliably under high radiation and industrial conditions is a different story.

The only established and industrial process is Plutonium Uranium Reduction Extraction (PUREX). It’s been used for decades and relies on extracting uranium and plutonium to refabricate MOX fuel (mixed Plutonium/Uranium oxide fuel).

Chalmer’s fingerprint in solvent extraction: CHALMEX

At Chalmers University of Technology, we have been developing a Swedish variant called CHALMEX (Chalmers Grouped ActiNide EXtraction). This process takes a slightly different approach; it aims to extract all actinides in one single step after removing the bulk uranium. This could make the separation more efficient, reduce the number of stages that are needed, and improve safeguards by avoiding pure plutonium streams entirely.⁴

CHALMEX uses a carefully designed solvent system:

- A fluorinated sulfone diluent (FS-13) as organic diluent.

- Two extractants: a nitrogen-donor ligand (CyMe4-BTBP) and an amide-based ligand, chosen to cover the complex coordination chemistry of the actinides.

The research aims to develop the chemistry of the CHALMEX separation process for spent nuclear fuel, with the goal of integrating it into fuel fabrication and obtaining starting materials for nuclear fuel from recycled sources.

The CHALMEX flowsheet typically has three main steps: extraction, scrubbing, and stripping. In the extraction stage, the target actinides transfer from the aqueous phase into the organic phase by forming complexes with the extractant. This is followed by a scrub step, which is mainly used to remove unwanted metals that co-extract in the first stage, in addition to scrubbing the nitric acid that is extracted in the first stage. Finally, in the stripping step, the actinides are back extracted into a pure aqueous phase, so they can be further processed and potentially recycled.

From chemistry to fuel: Bridging reprocessing and fabrication

Reprocessing alone isn’t enough. Once actinides are separated, we still need to convert them into usable fuel — a step that must meet high safety standards.

At Chalmers University of Technology, several projects work on this ‘fuel-to-fuel’ challenge. aimed to bridge the gap between separation chemistry and fuel manufacturing to create a fully integrated system.

Sol–Gel fuel fabrication: Turning liquids into solids

Traditional pellet fabrication relies heavily on powders, which can generate dust. One of the most promising fabrication routes for recycled fuel is the sol–gel process. This procedure allows us to convert liquid chemical solutions into solid ceramic fuel particles.

In this process, the starting sol consists of a metal nitrate solution to which gelation agents are introduced. Like the external gelation approach, the sol is subsequently dispersed through a nozzle to form droplets. However, in contrast to external gelation, the droplets are introduced into a heated organic diluent, typically silicone oil, and it has been dropped/maintained at range temperature from 50°C to 100°C, depending on the sol composition. The elevated temperature triggers the thermal decomposition of gelation agents, which results in a localised increase in pH. This pH shift initiates the gelation reaction within the droplets, leading to the formation of solid spherical particles, often called microspheres. Followed by heat treatment and sintering (heat-assisted densification) at a high temperature, these particles become ceramic fuel material.⁵

This method aims to fabricate what is known as nitride fuel. In this fuel type, the oxygen atoms in UO2 are placed with nitrogen atoms, forming the compound UN. This fuel matrix is favourable for recycled fuels because of properties that are favourable in reactors capable of using more transuranic elements than only plutonium as fuel. The nitride chemical forms of uranium and plutonium, for example, have a higher density than their oxide counterparts. The thermal conductivity is far higher than the oxide one, while the melt temperature is approximately equally high.

From that point on, fuel selection will be governed not only by today’s parameters but also by its recyclability.

Why fast reactors keep coming up

Recycled fuel is already used today, mainly in the form of MOX fuel, where recovered plutonium is blended with uranium and used in light-water reactors. But MOX has its limits, especially when it comes to multiple recycling loops or handling minor actinides.

Fast reactors address this limitation. In contrast to thermal reactors, which use moderators to slow neutrons down, fast reactors sustain the chain reaction with high-energy (fast) neutrons. The resulting neutron spectrum enables fission, and thus transmutation, of a broader set of isotopes, including minor actinides. This capability is especially relevant for closed fuel-cycle strategies, where plutonium and minor actinides recovered from spent nuclear fuel can be recycled as fuel rather than routed to disposal.

In simple terms, if you want to separate minor actinides, you need a reactor system that can use them. Fast reactors are one of the most discussed and suitable options for that.

In most long-term nuclear fuel strategies, you will often see fast reactors paired with grouped-actinide recycling.

What are the challenges beyond the lab?

Current work within the CHALMEX method is focused on investigating the challenges associated with process scale-up and identifying the types of equipment required for industrial implementation. However, it is important to acknowledge that closing the fuel cycle is more than chemistry or engineering. It involves major practical, economic, and societal challenges. Safety perspective must also be addressed, because spent nuclear fuel is highly radioactive, and all stages of the process, including dissolution, separation, conversion, and fuel fabrication, require robust shielding, containment, and criticality control. Economically, reprocessing and fuel fabrication facilities involve substantial investment, and the viability of recycling depends strongly on long-term energy strategies, uranium market conditions, and future reactor deployment. In addition, any system handling plutonium or minor actinides must comply with strict international safeguards and non-proliferation requirements; approaches that avoid the production of pure plutonium streams, such as CHALMEX, offer clear advantages in this perspective. Finally, public acceptance remains a critical factor, such as transport, recycling, and storage of nuclear materials, which demand transparent regulation, effective communication, and trust in institutions, playing a role as important as technical performance.

Conclusion: Recycling as part of a bigger energy future

The closed nuclear fuel cycle offers to use fuel as a resource rather than a disposal problem, recovering valuable materials, reducing the long-term burden of radioactive waste, and supporting advanced reactors that can make better use of what we have already mined and used.

But to get there, we need more than advanced separation chemistry. We need an integrated chain reprocessing, conversion, fabrication, reactor deployment, supported by safeguards, economic realism, and public trust.

In Sweden, initiatives like ANItA are helping to build that capability. As the country explores the role of SMRs and long-term nuclear energy, it’s critical to look not just at the front end, but also at the back end of the fuel cycle. Recycling may not be an easy option, but it could be a necessary one, and a powerful step toward a more sustainable nuclear future.

References

- World Nuclear Association. Global Nuclear Industry Performance. In: World Nuclear Performance Report 2025. World Nuclear Association, September 2025. World Nuclear Performance Report 2025 (PDF)

- Håkansson, A. ANItA – A new Swedish national competence centre in new nuclear power technology. Nuclear Engineering and Design, 418:112871, March 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nucengdes.2023.112871

- UK Government. Radioactive waste burning by nuclear transmutation: Technical report (Document No. 39402). UK Government, August 2025.

- Authen, T. L., Wilden, A., Schneider, D., Kreft, F., Modolo, G., Foreman, M. R. StJ., & Ekberg, C. (2021). Batch flowsheet test for a GANEX-type process: the CHALMEX FS-13 process. Solvent Extraction and Ion Exchange. https://doi.org/10.1080/07366299.2021.1890372

- Gonzalez Fonseca, L. G., Král, J., Hedberg, M., & Retegan Vollmer, T. (2023). Preparation of chromium-doped uranium nitride via sol-gel and carbothermic reduction. Journal of Nuclear Materials, 574, 154190.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2022.154190

Esraa Darwish

PhD Student, Energy and Materials, Chemistry and Chemical Engineering

Chalmers University of Technology

esraad@chalmers.se

Marcus Hedberg

Researcher, Energy and Materials, Chemistry and Chemical Engineering

Chalmers University of Technology

marhed@chalmers.se

Christian Ekberg

Professor

Head of Division, Energy and Materials, Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Chalmers University of Technology

che@chalmers.se

Please note, this article will also appear in the 25th edition of our quarterly publication.

Please Note: This is a Commercial Profile

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International.