An experiment at Texas A&M University has designed highly advanced quantum sensors to power experiments worldwide and is pushing the boundaries to explore the mystery of dark matter.

Led by Dr Rupak Mahapatra, the quantum detectors are so sensitive that they can pick up signals from particles that interact rarely with ordinary matter, revealing the nature of dark matter.

“The challenge is that dark matter interacts so weakly that we need detectors capable of seeing events that might happen once in a year, or even once in a decade,” Mahapatra explained.

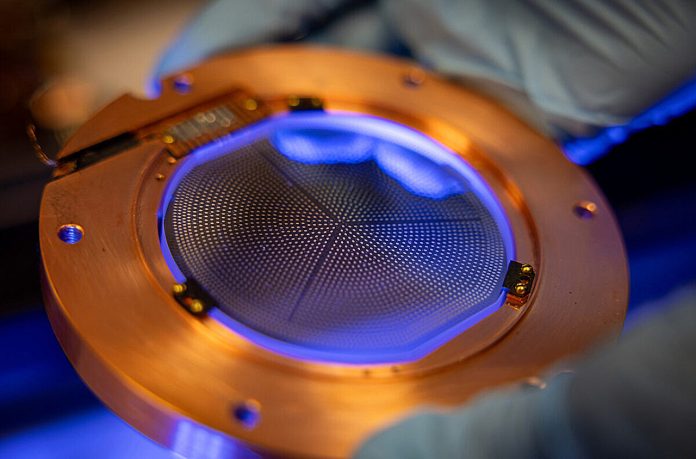

The experiment contributed to a world-leading dark matter search using the TESSERACT detector.

The unsolved mystery of dark matter and energy

Dark matter and dark energy make up about 95% of the Universe, leaving only 5% “ordinary matter,” or what we can see.

Despite their abundance, neither emits, absorbs, nor reflects light, making them nearly impossible to observe directly.

However, their gravitational effects shape galaxies and cosmic structures.

Dark energy is even more dominant than dark matter: it makes up about 68% of the Universe’s total energy content, while dark matter is about 27%.

When it comes to understanding the Universe, what we know is only a sliver of the whole picture. However, Mahaparta’s work could change this.

Pushing the limits of what’s possible

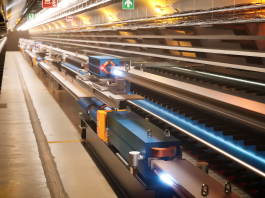

Mahapatra’s work builds on a long history of pushing detection limits through world-leading searches, with his participation in the SuperCDMS experiment for the past 25 years.

In a landmark 2014 study, he and collaborators introduced voltage-assisted calorimetric ionisation detection in the SuperCDMS experiment – a breakthrough that allowed researchers to probe low-mass WIMPs, a leading dark matter candidate.

This technique dramatically improved sensitivity for particles that were previously beyond reach.

Multiple experiments are needed to fully understand dark matter

More recently, in 2022, Mahapatra co-authored a study exploring complementary detection strategies – direct detection, indirect detection, and collider searches for a WIMP.

This work underscores the global, multi-pronged approach to solving the dark matter puzzle.

“No single experiment will give us all the answers,” Mahapatra stated. “We need synergy between different methods to piece together the full picture.”

Understanding dark matter isn’t just an academic exercise, it’s key to unlocking the fundamental laws of nature.

Mahaparta concluded: “If we can detect dark matter, we’ll open a new chapter in physics. The search needs extremely sensitive sensing technologies, and it could lead to technologies we can’t even imagine today.”