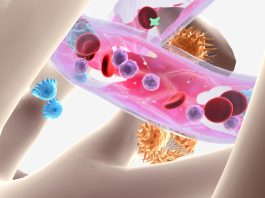

Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML), an aggressive and often fatal blood cancer, has long resisted a class of drugs called proteasome inhibitors, which work well in multiple myeloma.

A new study by University of California San Diego researchers shows why: AML cells activate backup stress-response systems to stay alive when proteasome inhibitors are blocked.

By combining proteasome inhibitors with a second drug that disables one of two backup survival pathways, the team was able to kill AML cells more effectively, reduce disease burden and extend survival in preclinical models.

Why are proteasome inhibitors alone not effective for treating AML?

The most common adult leukaemia, AML, is notoriously difficult to treat. About 70% of patients die within five years of diagnosis.

Current therapies are either broadly toxic, like chemotherapy, or narrowly focused on rare genetic mutations.

New research by Robert Signer, PhD, senior author and an associate professor in the Division of Regenerative Medicine at UC San Diego School of Medicine, and his team demonstrated why proteasome inhibitors alone are not effective against AML.

Unlike multiple myeloma cells, AML cells can use a backup system regulated by the HSF1 gene, or autophagy, to maintain health when such drugs are used. These emergency salvage and recycling pathways keep protein “rubbish” from piling up, even when proteasomes are disabled, allowing AML cells to maintain health and resist death.

Signer explained: “Imagine you’re driving down the highway and you hit construction, you just take an alternate route. When AML cells hit the ‘construction’ of proteasome inhibitors, they do the same thing by rewiring their network to take an off-ramp and continue their way.

“Multiple myeloma, on the other hand, remains stuck in traffic and becomes a sitting duck.”

Combined proteasome inhibitors slow down cell growth

By combining proteasome inhibitors with Lys05, a drug that impairs autophagy, the team was able to shut down AML’s detour.

In tests on AML patient cells, the combination slowed cancer cell growth and colonisation.

“Because AML involves so many potential gene mutations, it has made developing therapies quite difficult,” stated Kentson Lam, MD, PhD, first author and assistant clinical professor of medicine at UC San Diego School of Medicine.

“When therapies targeting specific gene mutations are successful, they only benefit the small subset of patients whose cancer carries those specific mutations. We wanted to help more patients by making this attack more mutation-agnostic.

“We tested this approach across a variety of AML cell lines and patient samples, and it worked across nearly all of them, regardless of their mutations.”

Improving treatment options for more patients

The researchers leveraged their expertise on stem cells – from which AML cells form, unlike multiple myeloma cells – to forge an alternate pathway for treatment.

They are now working to identify additional drugs that could disable AML’s backup survival strategies, with the goal of advancing combination therapies into clinical trials.

Signer concluded: “Targeting these protein pathways is a new approach to cancer treatment. Our hope is that this new research will improve treatment options for a wide range of AML patients.

“As scientists, that is our ultimate goal: to find new ways to treat disease to improve lives.”