Challenges and recent advancements in commercialisation of Enerocean’s W2Power semi-submersible design.

Floating technology can bring offshore wind to countries currently out of reach of this new planetary-scale renewable energy source. Commercialisation has been slower than many observers expected just three years ago.

This article discusses the delay and shows that, for floating wind technologies of genuine promise, commercialisation may accelerate sooner than today’s market expects. Three key conditions for success are 1) having a well-founded basis for cost reduction, 2) achieving required certification, and 3) continuing innovation in technology, performance, and manufacturability.

The case studied is the W2Power semi-submersible, a wind-vaning floater solution featuring a pair of wind turbines and other innovations to reduce steel mass per MW of rated power. It was the world’s first floater to achieve design certification at up to 15MW power. As other floaters reach similar levels of technology certification, the accuracy of assessing their relative cost-efficiency will improve, allowing site developers and financiers to compare commercial offerings directly.

Enerocean’s W2Power is one of the most mature floating wind technologies and the one with the highest power rating per tonne of platform steel. Over more than a decade of development, it has systematically advanced up the TRL levels and has reached all relevant milestones. Its competitive positioning for future markets derives from its fundamental design advantages. W2Power combines mature technology elements with a floater that has proven robust and scalable through major design revisions, with today’s commercial version at 20+MW. Using a pair of commercial turbines in the 10- to 12-MW class is a cost-efficient way to access the market offerings of competing turbine OEMs, combining access to best prices (for lower CapEx/MW) with good reliability (lower OpEx/MWh). W2Power’s low draft and ingenious single-point mooring keeps both turbines aligned in the wind using mainly passive alignment to yaw the full platform, eliminating the costly, error-prone nacelle yaw mechanism, thereby further improving OpEx.

height 126m above mean sea level

The technology has been proven by open-sea testing of a scaled prototype since 2019, as described in earlier articles.¹ The present paper reviews recent certification, sea testing, R&D and innovation activities. But first, a reality check on what the offshore wind business has lived through in the last 36 months.

Offshore wind: The market correction of 2023-25

Since 2022, a major market correction has affected offshore wind across Europe and North America. This is a noticeable slowdown from the high growth of previous years, which brought offshore wind capacity to 83GW, of which 37GW is in EU and UK waters (China leads with 42GW).² Drivers for the slowdown have been rising costs, supply chain constraints, and policy headwinds. This has caused auctions for new developments to attract few or no bids, approved projects to be cancelled, and others to be delayed.

Consultancy Wood Mackenzie³ lists more than 24GW of cancelled offshore wind projects in 2023-25. They now estimate that around 100GW of offshore wind will be operational by 2030 outside China, in stark contrast to the countries’ combined announced policy targets of 240GW. Consultancy TGS 4C reports⁴ that overall CapEx per MW for new-build projects rose to €3m in 2025 from €2.5m in 2022, while consultancy Rystad Energy gives⁵ typical LCoE for offshore wind as 110$/MWh in 2024/25, up from 75$/MWh in the period 2019-21.

Wind Europe has called for a ‘new deal for offshore wind’⁶ with governments guaranteeing 10GW new annual capacity by CfD contracts in 2031-40, plus 5GW/year on other regimes. It claims that EU industry could reduce costs by 30% with such a support guarantee.

Floating is only indirectly affected by the market slowdown since it remains an emerging segment with less than 0.5% of total offshore capacity (370MW in 2025). All floating installations to date have been demonstrators or at most small arrays of a few tens of MW. With the correction, this situation will continue for some years, since the costs of small projects are necessarily higher per MW. However, most investors do not realise that the cost structure and cost-reduction prospects for floating are quite different from those for bottom-fixed. This is due to supply chain differences, the rich variety of innovative designs in floating wind (offering potentially lower-cost breakthroughs), and the promise of faster scale-up by serial, modular manufacturing.

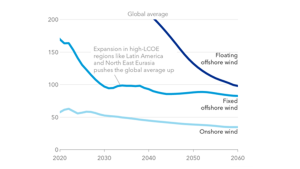

Certification body DNV has reduced their offshore wind expectation for 2030 to <190 GW worldwide⁷, citing “project delays, cost inflations and [US] bans and freezes”. They now predict that global LCoE will regain its downward trend for all windpower, expecting growth in offshore to pick up during the 2030s, contributing over half of new capacity in Europe, at LCoE just below 100$/MWh.

Even as they have moderated their overall growth predictions for offshore compared to past years, DNV still predicts floating to see GW-scale deployment from the early 2030s, driven by ‘strategic policy interventions’ in Europe and China. The resulting volume – estimated as 40GW by 2040 – will help to bring its global average LCoE below $200/MWh by 2040, and after that approach parity with fixed offshore over the next two decades.

Enerocean’s full-size demonstrator

While supporting the scenarios of DNV, who have a good understanding of floating wind, we note that calculating its ‘average’ cost today (of $390/MWh) is misleading, as it is based only on the single-unit demonstrators, or at most small arrays, which exist today or are in advanced stages of planning.

One such planned installation, with a much lower LCoE than DNV’s estimate, even as a first-of-a-kind, is the full-size W2Power demonstrator. Located in a commercial Port in the Canary Islands, it benefits from excellent wind resources, support by Port authorities and is near shore in an industrial area, in the Port waters. The project has already won part of its required funding as a Spanish national grant.⁸

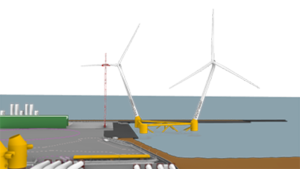

Despite delays caused by general headwinds and slow permitting, Enerocean plans this project to be, by 2030, Europe’s first 10MW+ floating-wind single demonstrator. Fig. 3 is a photo of the Port with a rendered image of the installation as it will appear from a vantage point 2km away.

Supply chain: Differences between floating and fixed

The supply chain for floating wind differs from that of bottom-fixed, whether on monopiles, jackets or gravity-based foundations. Fixed offshore resembles land-based construction, with large efforts dedicated to ground (seabed) preparation, fixing of piles and supports and lifting into place of large, heavy construction elements with a need for expensive specialised equipment. In contrast, making the constituent structures of floating wind has key features in common with shipbuilding: shaping and fabrication of steel structure elements, joining and assembly (usually by welding), and quayside load-out of the floaters to sea.

Moreover, while each type of fixed foundation needs different tools, support vessels and preparation of seabed, with differing availabilities and costs across the world, most types of floaters (e.g., steel semi-submersibles, barges and spar-buoys) are handled in much the same way, with less dependence on location. This has the important consequence that the competition between floater designs will be primarily on the relative costs of the floater for a given set of conditions. Therefore, floating designs with inherently lower cost, such as W2Power, will have natural advantages.

What fixed and floating offshore wind have in common is the need for ports and assembly/staging areas near the sea. Access to well-developed ports, securing healthy competition for offshore wind business, will be of great value for both fixed and floating value chains. As shown by the Enerocean demonstrator, Port authorities adapt to these emerging growth businesses and orient their future businesses by each country’s dominant resource (i.e., floaters in Spain, Italy, Norway and Japan).

Floating wind farms need mooring systems and dynamic power-export cables in addition to seabed power cables and transformer stations shared with bottom fixed. Moorings, anchors and required connectors are a mature field of engineering from shipping and oil and gas, available at competitive cost. Dynamic cables and the required wet- or dry-mate connectors are already commercialised (from the subsea oil and gas industry, but the volumes and cost/performance requirements differ.

Certification

The importance of certification is another insufficiently recognised characteristic of floating wind. In contrast to conventional offshore wind developers, the maritime industry has long recognised the power of certification and third-party classification in de-risking the building of ships and floating energy structures. Classification societies are private, recognised companies tasked with issuing and maintaining standards for safety in maritime and other businesses. The top five worldwide are DNV of Norway, US-based ABS, Lloyd’s Register (London), Paris-based Bureau Veritas, and ClassNK of Japan.

In 2023, W2Power was the world’s first floating wind platform to obtain a full design certificate for up to 15MW power.⁹ The Certificate of Basic Design Approval (BDA), awarded by Bureau Veritas, was the completion of a comprehensive assessment of the W2Power design, ensuring that best practices have been properly implemented. BV’s review of drawings, analyses and specifications showed that the W2Power design complies with relevant regulations and design codes. Enerocean’s BDA included the harshest wind and wave environments being considered for windpower.

Certification will be instrumental in the journey of safely bringing down costs and making floating offshore wind relevant in the future energy mix. A BDA represents the final verification of a floater design and implies an authorisation to proceed to large-scale construction, in Enerocean’s case, the full-size demonstrator. For such projects, and even more when moving to commercialisation, a BDA provides certainty to safety regulators, banks, insurers, project developers, and suppliers that the W2Power design can be trusted – thereby contributing to its overall bankability.

With other floaters following to reach this important milestone, such as recently that of Odfjell, also at 15MW,10 it will become easier in the future to assess and cost-compare commercial offerings on an equal footing. Ranking by cost is expected to be favourable for the certified W2Power. Enerocean being backed by a major energy group (Eni, its largest shareholder since 202211), should further help its commercial prospects in the future, whenever the markets are ready for floating wind expansion.

Continuing innovation

Enerocean has participated in collaborative R&D ever since its founding in 2007, winning a long string of EU, national and regional funded projects in highly competitive Calls. Recent ones range from lab R&D on long-term technological advances and applications to demonstrating at sea new innovative features of W2Power. The sea tests use the same scaled prototype first used to prove TRL 6 in 2019. Whereas other offshore energy prototypes are, in most cases, quietly scrapped, Enerocean carefully inspects the prototype (it is 1:8 scale of the current commercial design) after each test campaign, and maintains it by fitting improved components and monitoring systems.

As of this writing, the W2Power prototype is again at sea for the fourth testing campaign, planned to be its longest-lasting. It has so far seen the strongest wind ever at 24 m/s. To test the integrated fish cage holding live fish is the main purpose, using for the first time two commercial fish species. The work is part of AQUAWIND, a three-year project funded by the European Maritime, Fisheries and Aquaculture Fund. The fish cage itself, with several IP-protected innovations, was subjected to open-sea tests for six weeks with encouraging results. A previous paper12 reviews multi-use, including combinations of floating wind and mariculture, a new high-value application pioneered by Enerocean since 2012, for which the W2Power platform is particularly well suited.

Among strategic ongoing projects is SKILLS, our first Korean/Spanish bilateral project, with three Spanish partners funded by national innovation agency CDTI and five Korean partners funded by Korea’s sister agency KIAT, which focuses on wind-turbine developments and modelling twin-turbine installations.13 The recently started contract I3FLOAT, a €12m Horizon Europe project,14 will expand the scope of Enerocean’s innovation by working to strengthen the European floating-wind value chain for future commercialisation. This project supports four pilot activities, of which Enerocean leads one.

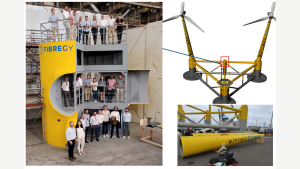

In the following, we highlight some results of the EU Horizon 2020 project FIBREGY, a now completed effort within advanced materials. Replacing steel parts with advanced composites has advantages in lightweighting, potentially reducing costs, and can improve performance specifically on floaters. This project funded the world’s first composite floating turbine towers, installed on the W2Power prototype, see Fig. 6 and 7. They performed very well and are still in use for our open-sea testing.

structural monitoring system

FIBREGY also implemented a full-size demonstration of replacing an entire structural element of the floating platform. The project team designed a full-size version of the upper half of the ‘D’ column, an important structural element in W2Power. The result is seen in Fig. 7. Notice the full FIBREGY team of engineers and materials scientists, populating this 1:1 build of the (smallest) column, serving as a useful reminder of the substantial remaining challenges involved in bringing W2Power to full scale and commercial market introduction.

References

- The Innovation Platform 11: p.146-147 (Sept 2022); 13: 192-93

(March 2023) - Global Wind Energy Council, 2025 Annual Report, Aug 2025

- Wood Mackenzie 21.11.2025

- As reported by Financial Times, 19.10.2025

- S. Leinan (Rystad Energy), Science Meets Industry, U. of Bergen, 04.11.2025

- Wind Europe press releases 04.09.2025 and 05.11.2025

- DNV Energy Transition Outlook 2025, 25.10.2025

- Enerocean Primavera project, Wind Europe, Bilbao 20-22 March 2024

- W2Power receives design approval from Bureau Veritas, 16.11.2023

- Odfjell Oceanwind granted Basic Design Approval, 11.11.2025

- Plenitude invests in Enerocean’s floating wind technology, 22.04.2022

- The Innovation Platform Issue 15: p. 220-222 (September 2023)

- Enerocean’s SKILLS project

- I3FLOAT project launched, 23.10.2025

Please note, this article will also appear in the 24th edition of our quarterly publication.