The DiDAX consortium is enabling a vision of DNA as a versatile medium for secure and long-term data applications.

DiDAX is a consortium of eight research groups, coming from both academia and industry and working together, under EU EIC funding, to innovate DNA-based data applications. Our work is based on novel encoding and decoding algorithms, reduced cost flexible synthesis, novel chemistries and new protection and embedding technologies and material science innovations.

Innovating in these disciplines, DiDAX expands the applicability of long-term archival DNA-based data storage and develops new applications to protect, verify and object authenticity.

DNA, as an information storage medium, has many advantages. First, DNA’s density – it can store extraordinary amounts of data in an extremely small volume. To illustrate the scale, if all the information currently hosted on YouTube were encoded in DNA, it would, in theory, fit in a single shoe box. Second, DNA is inherently stable, and we understand how to preserve it for extremely long periods. Third, DNA is environmently friendly in having little associated energy cost, compared to magnetic media in data centres and in reducing electronic waste. And finally, its longevity and universality – DNA is the fundamental building block of life. As long as humans (and biology) exist, we will possess the tools and knowledge to read, write, and interpret DNA, unlike legacy storage technologies such as magnetic tapes, VCRs, or obsolete disk formats that became unreadable.

Together, these and more make DNA an attractive medium for long-term, archival data storage.

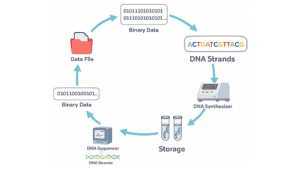

Here is how we can (and indeed do so, in DiDAX) store data in DNA.

A DNA strand is a sequence built from four nucleotides, which together form a four-letter alphabet (A, C, G, T). Since modern synthesis technologies allow us to chemically create almost any DNA sequence we choose, we can treat DNA as a programmable storage medium. The process begins by taking a digital file and converting it into a binary representation (e.g., 00110010101). We then encode the binary string into DNA letters using a predefined mapping such as 00 → A, 01 → C, 10 → G, 11 11->T. After encoding, the DNA sequences are chemically synthesised and stored in a physical container. For better sustainability encapsulation, chemistry may also be applied. Error correction codes are also used to address corruption that can occur in the process.

To retrieve the information, the stored DNA is sequenced using DNA sequencing technology (such as Illumina or Oxford Nanopore). Sequencing reveals the nucleotide order of the strands, which is then decoded by applying the same mapping in reverse, including algorithmic error correction, to reconstruct the original binary data and the original file.

Using techniques from cryptography, computer science and coding, we are also developing in-product information storage solutions and DNA-based authentication and tracing protocols. DNA has an advantage in this context since it can be embedded into many materials and, therefore, labelling using DNA is not restricted to external packages or to specific parts of objects or products. Further advancing the applicability of DNA as a labelling and authentication reagent is also supported by our materials science research.

DiDAX activity already has science and technology impact in several domains, including industrial collaboration, and is reported in several leading scientific journals.

Let’s describe, in more detail, some of the specific activities in four example directions.

1. Flexible DNA synthesis and efficient encoding

Multiple technologies have been developed for the large-scale synthesis of DNA libraries. All these technologies are based on achieving spatial control of synthesis on surfaces, often resulting in DNA oligonucleotide microarrays. These DNA microarrays were first used for genomics applications, but replacing biologically relevant oligonucleotides, such as gene fragments, with DNA encoding digital information and cleaving the molecules from the surface for storage and subsequent decoding via sequencing, allows the DNA to be used as a storage medium.

Currently, the synthesis of the DNA is by far the most expensive part of any DNA-based storage process. To a significant extent, this cost supports biological applications where sequence fidelity is a principal consideration. The three most prominent large-scale DNA synthesis approaches are: ink-jet printing, in which spatial control is achieved with high precision delivery of droplets containing the DNA monomers (phosphoramidites); electrochemical, based on controlled polymerisation of DNA using semiconductor microchips and arrays of anodes and cathodes; and photolithography, which uses spatial control of light similar to that used in the microchip industry, to control synthesis via selective removal of photolabile groups on the DNA phosphoramidites.

DiDAX uses digital photolithographic DNA synthesis for the de novo creation of very large libraries of more than 2 million unique oligonucleotides with lengths of up to about 120 nt. Here, a digital micromirror device with about 2 million individually controllable micromirrors is used to control synthesis (Fig. 2). This synthesis approach allows close and flexible control of the chemistry and photochemistry, resulting in unique opportunities to increase the density of information encoded in the DNA at low cost, such as through the use of composite alphabets (see below). This flexibility also allows for incorporating non-canonical nucleotides such as deoxyuridine (dU) and 5-methylcytosine (m5C) and for synthesising more complex structures such as 5 prime to 5 prime junctions. The latter are useful in authentication and protection applications.

In many ways, photolithographic DNA synthesis is optimal for dynamic DNA data and information applications. It is an accessible technology that does not require an industrial infrastructure, and it allows for innovative encoding approaches, flexible chemistry and reduced cost. The latter may be at the expense of an increased error rate – a trade-off that makes sense in the context of data storage in DNA, where error-correcting codes can be used (see below). In DiDAX, we are exploring how best to increase the information density in DNA while keeping the synthesis costs as low as possible, to make DNA data and information applications practical and affordable. For more on DNA Synthesis see Hölz et al.

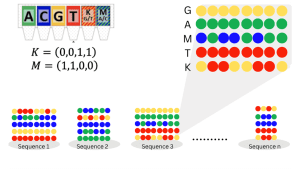

One of the central challenges in data storage using DNA is to maximise the information stored per synthesised position (bits/symbol) or per synthesis cycle time. Initially, if we restrict ourselves to the standard four DNA bases – A, C, G, T – the theoretical limit is 2 bits per symbol. To improve this limit and enlarge the alphabet size, instead of synthesising a single pure base at each position, we can use composite letters as follows. A composite letter, over the standard DNA alphabet (can be extended), is specified as a vector σ=(σA,σC,σG,σT) where each entry describes the relative frequency/proportion of A,C,G and T, with a resolution parameter k=σA+σC+σG+σT. The full composite alphabet of resolution k, denoted as Φk, contains all such combinations yielding (k+3) distinct composite letters. For example, with k=2 we will have ten letters: x1=(1,1,0,0),x2=(1,0,1,0),…,x10=(0,0,1,1). In this example, x1 is a letter represented by an equal mixture of A and C (M in Fig. 3). Fig. 3 illustrates an example of a composite alphabet.

More on composite alphabets, see in Anavy et al, Preuss et al, Cohen et al. Further extending and improving the use and applicability/cost of composite alphabets is pursued by DiDAX in collaborative projects led by several partners.

2. Coding and sequencing for archival data storage

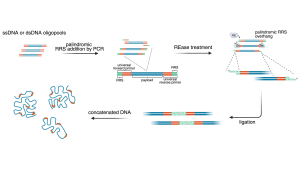

DNA-based data storage relies on encoding digital information into DNA sequences that can later be read using standard DNA sequencing technologies. Chemically, this DNA is the same as biological DNA, meaning it can be analysed using commercially available sequencers. The main challenges are therefore not in reading the DNA itself, but in how the DNA is synthesised, encoded, and prepared for efficient data retrieval. Current DNA synthesis technologies, including enzymatic and photolithographic methods, typically produce short DNA fragments of around 100–300 nucleotides. While short DNA fragments are suitable for data storage, they are not optimal for sequencing, particularly for certain DNA reading technologies, as they can reduce both sequencing accuracy and throughput.

DNA sequences must also be carefully designed to ensure reliable readout. First, as both synthesis and sequencing introduce errors into the DNA molecules, they have to be designed using Error-Correcting Codes (ECCs). In DNA, the error profile includes substitutions, deletions, and insertions; the latter two are less common in existing data storage technology. Hence, unique and novel ECCs and other error-correction techniques are required for DNA data storage. Additionally, certain patterns, such as long homopolymers, can introduce sequencing errors, while the overall balance of DNA bases must be controlled to maintain stability and readability. This requires the use of constrained coding strategies when converting digital information into DNA. See more in Sabary et al, Nguyen et al.

For archival data storage, fast and efficient access to information is a key requirement. Hence, retrieval algorithms for DNA-based data storage need to be efficient and capable of processing large amounts of information. Nanopore-based sequencing technologies are particularly well-suited for this purpose. These devices are relatively inexpensive, portable, and can be operated outside highly specialised laboratory environments. Importantly, they provide access to data in near real time, as DNA molecules are read continuously during the sequencing process.

Nanopore sequencers perform best with long DNA strands, which creates a mismatch with short synthetic DNA fragments. To address this, we are developing methods to join short DNA molecules into longer strands through a process known as concatenation. Once concatenated, sequencing efficiency and data quality improve significantly. Longer DNA strands reduce losses during preparation, and enable the use of simpler and more robust sample preparation workflows. As a result, sequencing becomes faster, more efficient, and better suited for the rapid retrieval of archived digital data.

3. Stability of DNA as an information medium and labelling applications

To be able to store data in DNA for the long term, the stability of the storage medium has to be addressed. DNA suffers from chemical decay: spontaneous hydrolysis, depurination, deamination, and oxidative lesions continuously cleave the backbone and modify bases, limiting the half-life of non-protected DNA to a few months at room temperature (see Grass et al ).

Encapsulation in amorphous silica particles creates ‘synthetic fossils’ that protect the DNA from water and, thereby, limit decay by hydrolysis. In this encapsulated format, the half-life of DNA is extended to several hundreds of years, making it the most stable digital data carrier. In addition to providing stability, the silica encapsulation of DNA enables the integration of DNA into bulk materials; the DNA of things (DoT) architecture embeds silica-encapsulated DNA within polymers such as polycaprolactone or polymethyl methacrylate, allowing 3D printed or cast objects to carry immutable digital blueprints and labels. Because the encapsulated DNA can be released intact, it can serve as an inert, durable taggant for product tracing, supply chain verification, and medical implant record keeping, providing a chemically robust molecular label that survives harsh processing, heat, and oxidative environments while preserving the encoded information for decades or longer.

Within DiDAX, we are working on extending the scope of compatible materials for DNA integration, with the goal of having DNA as a common technology to store valuable product information within the products themselves. An example thereof is the Necto project (pictured), a 3D-knitted installation, which was exhibited at the 19th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia. The design is based on locally sourced, biodegradable flax fibres, created between the architecture studio Solid Objectives Idenburg Liu, Mariana Popescu and design and research practice TheGreenEyl. The technological and scientific basis for 3D knitted formworks is the result of a successful collaboration between TU Delft and the D’Acunto Lab of TU Münich within the EU-funded project FlexiForm. Data storage within DNA was developed within DiDAX. The digital material passport, comprising details of materials and machine instructions required to produce the textile itself (10 kB of digital data), was encoded in DNA, and millions of copies of the DNA file were distributed within the actual structure for future read-out.

4. Cryptography and authentication using DNA

Beyond data storage, DiDAX is developing DNA-based authentication and tracing protocols that help verify whether a physical item is genuine and where it came from, even after packaging has been removed. The basic idea is simple: instead of relying only on printed labels, QR codes, or holograms that can be copied or swapped, a manufacturer can embed a tiny amount of synthetic DNA tag reagents directly into inks, coatings, plastics, textiles, food items or any other product or object materials. Because the tag becomes part of the object itself, authentication can be performed ‘in-product’ at different points in the supply chain – at manufacturing, distribution, retail, or during audits.

DNA tagging is even more useful when it goes beyond ‘reading a code’. As sequencing and synthesis become more accessible, a determined counterfeiter may try to sequence a marker and reproduce it. DiDAX therefore connects DNA tagging with ideas from modern cryptography: authentication should be based on mechanisms that remain verifiable under noise, yet are difficult to clone or predict in practice.

A key building block to support this direction was recently introduced by DiDAX partners: Chemically Unclonable Functions (CUFs) based on operable random DNA pools. In a CUF, the tag is not a single designed sequence, but a large and complex random mixture created during production. To authenticate, a verifier applies a challenge (for example, specific laboratory query steps such as primer-pair-based amplification) and measures the response by sequencing. The response is then compared to a reference recorded at enrolment. This challenge–response approach resembles the approach of Physical Unclonable Functions (PUFs) used in hardware security, where manufacturing randomness becomes a fingerprint. For more on CUFs see: Luescher et al.

In DiDAX, we generalise this concept into a broader framework of chemical functions and adapt PUF security properties — such as uniqueness across items, reproducibility under measurement noise, and resistance to modelling or cloning — to chemical settings. This enables a clearer security analysis for future schemes to be developed: what is assumed about the attacker’s capabilities, what can be verified, how errors affect decisions, and how design choices trade cost against confidence and/or security.

While the primary focus is anti-counterfeiting and traceability, the same chemical-function view also supports related applications such as key generation, where stable physical randomness can be used to derive digital secrets. Overall, DiDAX’s goal is to develop DNA-based authentication into a systematically engineered security tool that can be deployed across real products and real supply chains.

In summary, DiDAX is redefining the boundaries of information systems by transforming DNA into a robust, high-density medium for storage and information applications. Through the integration of flexible synthesis, advanced error-correction coding, and secure molecular tagging, DiDAX is making long-term archival storage and in-product solutions, based on DNA, both practical and scalable, ensuring that our most valuable data and products remain resilient and accessible for generations to come.

Disclaimer

Funded by the European Union (DiDAX, 101115134). Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Please Note: This is a Commercial Profile

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International.

Please note, this article will also appear in the 25th edition of our quarterly publication.