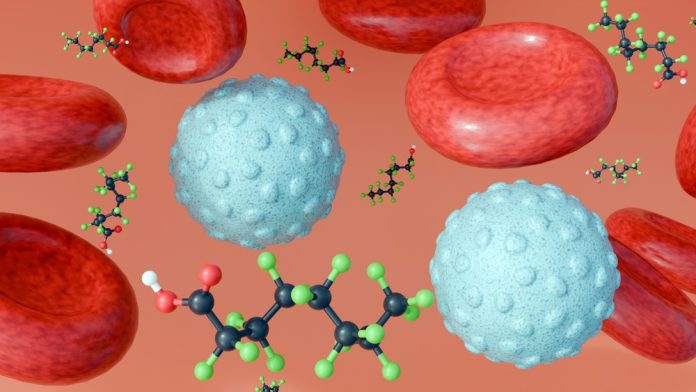

New research from North Carolina State University discovered high levels of short-chain PFAS in blood samples taken from Wilmington, North Carolina, residents between 2010 and 2016.

Two ultrashort-chain PFAS – perfluoromethoxyacetic acid (PFMOAA) and trifluoracetic acid (TFA) – were detected at high levels in almost every sample. In contrast, GenX – the chemical that jump-started public concern about PFAS in the Cape Fear River Basin – was detected in 20% of the samples.

The research adds to the body of evidence that short-chain PFAS can accumulate in the human body.

Short-chain PFAS in human blood is not well understood

Ultrashort-chain PFAS, such as PFMOAA and TFA, have not been well studied in people for two reasons: they were not thought to bioaccumulate due to their chemical structure, and until recently, there were no analytical methods to reliably detect them in blood.

“With the development of analytical methods targeting ultrashort-chain PFAS, researchers have found these compounds to be the dominant PFAS in environmental matrices, including water and human blood,” explained Detlef Knappe, professor of civil, construction, and environmental engineering at NC State and co-corresponding author of the study.

“Given the long history of PFAS exposure in Wilmington, we wanted to look for these compounds in historical water and blood samples of residents.”

In 2016, NC State and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency researchers published findings highlighting high concentrations of several PFAS, including GenX, in Wilmington residents’ drinking water.

The Fayetteville Works plant, an upstream chemical facility, had been releasing PFAS into the Cape Fear River, the city’s primary drinking water source, since 1980. After 2017, the chemical manufacturer was required to control PFAS discharges into the river and air.

High levels of PFAS in drinking water could be behind exposure to humans

For the new research, the researchers analysed 56 PFAS in water samples from the Cape Fear River collected in 2017, as well as in 119 adult blood serum samples from a UNC biobank collected between 2010 and 2016. The serum samples were anonymised, but all were collected from residents in Wilmington and its surrounding areas.

The findings were surprising. In the blood serum, 34 of the 56 PFAS were detected in at least one serum sample. Five PFAS accounted for 85% of the total found in the samples. PFMOAA had the highest median concentration at 42 nanograms per millilitre (ng/mL), comprising 42% of the summed total, followed by TFA (17 ng/mL), PFOS (14 ng/mL), PFOA (6.2 ng/mL), and PFPrA (5.4 ng/mL).

Additionally, they found that TFA accounted for 70% of the total PFAS in the 2017 water sample, with a concentration of 110,000 nanograms per litre (ng/L). PFMOAA had a concentration of 38,000 ng/L.

While TFA has a variety of sources, including fluorinated refrigerants, the publication highlights that Fayetteville Works was the dominant source of both TFA and PFMOAA in the lower Cape Fear River.

“For reference, one European guideline recommends a drinking water level of 2200 ng/L for TFA. Our sample contained over 50 times that concentration,” Knappe stated.

More research about human exposure to short-chain PFAS is needed

Jane Hoppin, professor of biological sciences, principal investigator of the GenX Exposure Study, commented: “The conventional wisdom is that short-chain PFAS are of lesser concern because they don’t bioaccumulate, but what we’re seeing is that they can occur at high levels in people.

“These results point out the need to start thinking about how to study the human health effects of these PFAS, particularly TFA and PFMOAA.”

Another issue is the limited human health data available for any of these chemicals. Most chemicals in the PFAS class affect the liver and immune system, but this work is still in its infancy in many cases.

The next steps in this research include analysing samples from the GenX Exposure Study for TFA and PFMOAA levels.

Hoppin concluded: “Seeing what the levels are now will help us determine how these chemicals accumulate in the body and what their health effects might be.”