New research from the Research Institute of Sweden (RISE) shows livestock adapt long-term to virtual fencing, offering new insights into animal behaviour.

Across Europe, livestock farmers face the complex challenge of ensuring food security while delivering on environmental targets, fostering animal welfare, and adapting to labour shortages.

Traditional methods of livestock management have long relied on physical fences for controlled grazing. These structures can be labour-intensive to build, maintain, and repair, while also disrupting landscapes and often causing stress or injury risks to animals. At the same time, pressures on the agricultural sector are increasing: from environmental regulations and biodiversity targets to demands for more efficient production and higher animal welfare standards.

Since its commercial launch five years after its foundation in 2011, Nofence’s virtual fencing system has emerged as a transformative tool for livestock management and the agricultural sector as a whole. By replacing physical barriers with GPS-enabled collars that guide animals through the pastures using audio cues, the technology gives farmers greater flexibility while supporting natural grazing behaviours. It reduces the need for manual labour, minimises the risk of injury, and creates new possibilities for managing livestock across challenging terrains or conservation areas.

Research has already demonstrated how livestock adapt to virtual fencing during the training period, with animals quickly learning to respond to audio cues and experiencing minimal stress. Building on this solid foundation, new studies are now beginning to provide insights into the long-term adaptation of livestock to the technology, showing how behavioural change is reinforced over time.

Virtual fencing at a glance

The Nofence system combines GPS-enabled collars with a user-friendly mobile app, which allows farmers to easily set up and adjust virtual boundaries, giving them flexibility to manage grazing areas in real time.

When an animal approaches a boundary, instead of an immediate correction, the collar plays a series of audio cues that increase in pitch as the animal moves closer, allowing it to calmly react and turn around. Only if the repeated cues are ignored does the collar deliver a mild electric pulse, half the intensity of a physical electric fence, as a last resort. Over time, these corrective pulses become less and less needed, leading to a more relaxed grazing environment.

To support this learning process, Nofence designed a training process that ensures the highest level of animal welfare. Animals are first introduced to the collars in a training pasture where three sides are enclosed with physical fencing and the fourth with a virtual boundary. In this phase, the collars operate in ‘teach mode’: even a small change in direction switches off the audio cues, helping animals make the connection swiftly and predictably. Most animals adapt quickly, with data showing that 96% of interactions are resolved without the need for a pulse after the first initial training phase.

Livestock are highly social, and their reactions often influence the rest of the group. Once a few animals learn to respond to the audio cues, others quickly follow, reinforcing collective learning and reducing stress across the herd. This synchronised behaviour means that animals adapt not just individually, but collectively, creating a stable and predictable grazing environment. Over time, this group dynamic strengthens the association between sound and the boundary, further minimising the need for corrections and helping maintain a calm, low-stress atmosphere for the entire herd.

Research-backed welfare outcomes

A growing number of independent studies confirm that virtual fencing is both effective and welfare-friendly. Multiple studies have compared the system to physical electric fencing and found no significant differences in stress indicators, such as cortisol levels, and found no negative impact on behaviour or body weight gain.

Research published in Animal¹ The International Journal of Animal Biosciences, examined the use of Nofence collars with heifers grazing on mountain pastures in Switzerland. The study found that virtual fencing was as reliable as electric fencing in preventing escapes, and that animals consistently adapted to the system. Activity patterns, including circadian rhythms, remained highly stable, indicating that animal welfare was not compromised even in the challenging conditions of an alpine environment.

Additionally, a comprehensive review in Frontiers in Veterinary Science² highlighted that welfare impacts should be evaluated through both physiological indicators (such as cortisol levels) and behavioural responses. The review concluded that animals adapt successfully without adverse outcomes when systems are designed to provide predictability and control in their environment.

Together, these findings provide consistent evidence that Nofence upholds animal welfare while giving farmers greater flexibility in how they manage grazing. Most of this research, however, has focused on the training period and short-term adaptation.

To expand this picture, researchers at the Research Institute of Sweden (RISE) have collected and analysed a two-year dataset from animals wearing Nofence collars, helping address an important gap in the scientific evidence.

Long-term animal adaptation

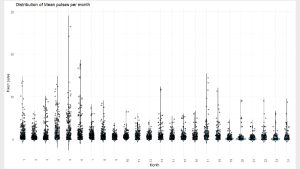

Their analysis offers the first detailed look at long-term adaptation, showing how animals refine their behaviour over months and years of using the system. Looking at a two-year dataset, researchers observed a steady decrease in the number of pulses delivered (Fig. 1), indicating that animals increasingly responded to sound cues alone rather than receiving a correction. While the number of animals involved varied during the study period and further research is needed to confirm these trends, the results align with what farmers and earlier trials have consistently shown: once trained, livestock quickly learn to work with the system.

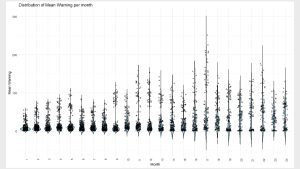

The same dataset shows that warnings increased over time, a positive sign that animals were encountering the virtual boundary more often (Fig. 2) but choosing to respect it upon hearing the escalating audio cues. Instead of breaching the boundary, they turned back, demonstrating the collars’ ability to guide behaviour primarily through sound rather than corrections.

of warning signals per animal over a month

Considered in their entirety, the findings from RISE highlight that Nofence’s technology is not just effective in the short term. Over time, livestock continue to adjust their responses, relying more heavily on audio cues and showing evidence of long-term adaptation to virtual fencing.

Success rates also improved month by month (Fig. 3), reinforcing the picture of long-term behavioural change. Animals were not only learning the association between sound and the boundary during the training period, but also continued to strengthen this behaviour over time.

The data also shows occasional spikes in pulses or breaches after long periods of stability. While the exact reasons remain unclear, these anomalies are likely linked to the introduction of new, untrained animals inheriting collars, or seasonal changes in pasture layout. Importantly, such outliers proved temporary, with stability returning as animals adapted to the system.

Conclusion

Virtual fencing has already proven itself as an essential tool for farmers for controlling grazing for cattle, sheep, and goats, combining animal welfare, flexibility, and sustainability in one system. The latest findings from RISE show that livestock not only adapt quickly but continue to refine their behaviour over time, relying increasingly on audio cues rather than corrections.

Alongside existing research, this long-term evidence reinforces how Nofence supports both the wellbeing of animals and the practical needs of farmers, while contributing to more sustainable land management.

References

- P. Fuchs, C.M. Pauler, M.K. Schneider, C. Umstätter, C. Rufener, B. Wechsler, R.M. Bruckmaier, M. Probo, Effectiveness of virtual fencing in a mountain environment and its impact on heifer behaviour and welfare, animal, Volume 19, Issue 8, 2025, 101600, ISSN 1751-731,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.animal.2025.101600 - Caroline Lee, Dana L. M. Campbell, A Multi-Disciplinary Approach to Assess the Welfare Impacts of a New Virtual Fencing Technology, Frontiers in Veterinary Science, Volume 8 – 2021

https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2021.637709

Please note, this article will also appear in our Animal Health Special Focus publication.