New research from Imperial College London has revealed how ‘pirate’ bacteriophages hijack other viruses to infect bacteria and combat drug-resistant infections.

Bacteriophages hijack other viruses to break into bacterial cells and spread, a process that could potentially be harnessed for medical use to treat drug-resistant infections.

This discovery reveals an intriguing new mechanism by which bacteria acquire new genetic material, including traits that could render them more virulent or more resistant to antibiotics.

However, the researchers believe that these pirate phages open new avenues in tackling the global health threat of antibiotic resistance and in developing rapid diagnostic tools.

What are bacteriophages, and how do other viruses impact them?

Bacteriophages are viruses that infect and kill bacteria. They are among the most abundant organisms on Earth and are often highly specific, each tailored to attack just one bacterial species.

Structurally, they resemble microscopic syringes: with a ‘head’ section packed with DNA and a tail section tipped with spiky fibres that latch onto bacteria and inject their genetic payload.

Despite this, phages still aren’t safe from parasites. They can be targeted by small genetic elements called ‘phage satellites’ that hijack their own genetic machinery to multiply.

As part of the research, the team focused on a powerful family of phage satellites called capsid-forming phage-inducible chromosomal islands (cf-PICIs). These genetic elements can spread genes for antibiotic resistance and virulence and are found across more than 200 bacterial species.

Exactly how they managed to move so efficiently, however, was unclear.

How cf-PICIs attack other bacterial species

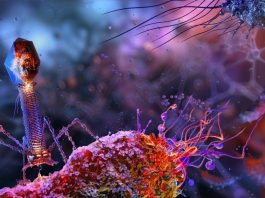

First discovered by the team in 2023, cf-PICIs can build their own capsids (the viral ‘heads’), but they lack tails, meaning that on their own, they produce non-infectious particles and are unable to infect bacteriophages.

In their latest work, researchers discovered the missing piece of the puzzle: cf-PICIs hijack tails from unrelated phages, creating hybrid “chimeric” viruses. The result is a chimeric phage carrying cf-PICI DNA inside its own capsids, but a phage-derived tail attached.

Crucially, some cf-PICIs can hijack tails from entirely different phage species, effectively broadening their host range. Because the tail determines which bacteria are targeted, this piracy enables cf-PICIs to infiltrate new bacterial species, explaining their widespread abundance in nature.

Developing powerful new diagnostics for ABR

According to the researchers, the implications could be important for science. By understanding and harnessing this molecular piracy, researchers believe they could re-engineer satellites to target antibiotic-resistant bacteria, overcome stubborn bacterial defences such as biofilms, and even develop powerful new diagnostic tools.

“These pirate satellites don’t just teach us how bacteria share dangerous traits,” explained Dr Tiago Dias da Costa, from Imperial’s Department of Life Sciences. “They could inspire next-generation therapies and tests to outmanoeuvre some of the most difficult infections we face.”

Professor Jose Penades, from Imperial’s Department of Infectious Disease, added: “Our early work first identified these odd genetic elements, where we found they are effectively a parasite of a parasite.

“We now know these mobile genetic elements form capsids which can swap ‘tails’ taken from other phages to get their own DNA into a host cell. It’s an ingenious quirk of evolutionary biology, but it also teaches us more about how genes for antibiotic resistance can be spread through a process called transduction.”

The Imperial team has successfully filed patents to develop the work further and hopes to begin testing the translational applications of the technology.

AI co-scientist tool makes new advances

In a linked project, coordinated through the Fleming Initiative – a partnership between Imperial College London and Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust – researchers utilised their experimental work to validate a groundbreaking AI platform developed by Google.

Dubbed the ‘co-scientist’, the platform is designed to help scientists develop smarter experiments and accelerate discovery.

To test the platform, the Imperial team posed the same basic scientific questions that had driven their own work: How do cf-PICIs spread across so many bacterial species?

Armed with this starting point, and drawing on web searches, research papers, and databases, the AI independently generated hypotheses that mirrored the team’s own experimentally proven ideas – effectively pointing to the same experiments that had taken years of work to establish but doing so in a matter of days.

The researchers say this shows the extraordinary potential of AI systems to ‘super-charge science’, not by replacing human insight, but by accelerating it.