An award-winning team of scientists has been able to recreate cosmic processes in a laboratory setting, confirming a phenomenon that explains the formation of stars and planets. Editor Georgie Purcell spoke to one of the lead researchers, Hantao Ji, to learn more.

Imagine being able to see stars and planets forming right in front of you. After decades of work, scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) and Princeton University have managed to achieve just that.

For over 20 years, the Magnetorotational Instability (MRI) Experiment at PPPL has been researching how swirling matter can form stars, planets, and supermassive black holes. In a recent discovery that has earned them the prestigious John Dawson Award in Plasma Physics, the team has officially confirmed a phenomenon, called MRI, that explains planet and star formation, as well as matter falling onto neutron stars and black holes.

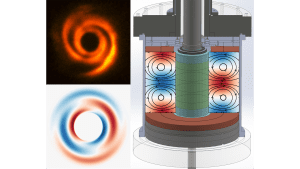

The experiment consists of understanding and recreating the MRI process involving accretion disks of swirling matter in space that wobble in a very specific way. The process leads to turbulence, which causes matter to spiral inward, ultimately forming massive objects in space. This is only possible due to the presence of plasma and magnetic fields, which combine to allow the wobble to occur.

Utilising experimental ingenuity, theoretical insight, and advanced computational modelling, the team centred their work on an uneven wobble by MRI. It has long been theorised that this type of wobble can form planets and stars, but has never been confirmed in any real-world settings. The team was the first to study it theoretically and then recreate the process in a laboratory setting.

To find out more about the experiment, the challenges encountered along the way, and the significance of the discoveries made, Georgie Purcell spoke with Hantao Ji, Professor of Astrophysical Sciences at Princeton University and Distinguished Research Fellow at PPPL.

Can you explain more about the background of your work and the main goals of the experiment?

In astronomy, it is usually difficult to observe and try to understand things that happen at a faraway distance. Typical models of research include theory and numerical simulations. Our work, however, is focused on bringing the things that happen in the sky right in front of us. This is an important new way to do research, creating new possibilities for everyone.

The Magnetorotational Instability Experiment is centred on recreating the process of star formation. To form stars, material must move into the middle of a molecular cloud. However, this is not easy, as finite angular momentum prevents it from moving into the centre. Like with Earth moving around the Sun, angular momentum prevents Earth from falling into the Sun. To reach the centre, you need a process like magnetorotational instability. The key is not to destroy the angular momentum, but to give most of the angular momentum (like 99%) to a small amount of the mass (like 1%). The 1% mass carries 100% of the angular momentum, but the 99% mass doesn’t have angular momentum. Therefore, this 99% can travel to the middle whilst the 1% stays out. In this sense, the 1% becomes a planet, and the 99% becomes the Sun. To summarise, the trick of this MRI is to redistribute – you must shift angular momentum from the material that wants to go to the centre, to the material that doesn’t want to go to the centre.

To create this transfer, we must couple the magnetic field and plasma, which is an electrically conducting fluid. For this experiment, we used liquid metal to stand in for plasma. We make an ‘accretion disc’ in the lab by rotating liquid metal. Then, we impose a magnetic field to trigger MRI which transfers the angular momentum from one part of the liquid metal to the other part.

Did you encounter any surprises within the experiment?

The main surprise was that we found things a lot more challenging than we initially thought. We expected to be able to realise MRI very easily. We know we can build a drum to rotate and we can impose magnetic fields. That’s simple. However, the surprise was in the edge effect.

In an ideal drum, the cylinder is infinitely long. That’s not a problem in theory, as you can theorise a problem assuming the cylinders go to infinity. However, when recreating this in a lab environment, it must be finite due to limited space. When it is a finite length, the edge effect becomes important.

In astrophysics, the same issue is not apparent because accretion disks have free boundaries when floating in the sky as gravity helps to bound the material. Unfortunately, in the lab we need to have a cap to prevent the liquid metal from falling out. The cap becomes the issue.

We need to rotate the liquid metal, but the rotation is not a solid body rotation. It requires a differential rotation – faster inside, slower outside. Very much like Venus rotates much faster than Earth around the Sun. This is easy to achieve with liquid as it can have different rotations. But the solid cap can’t have different angular velocities at different radii – the whole cap has to rotate at only one speed. This does not match the differential rotation of the liquid metal, which is a problem. It took us 20 years to overcome this mechanical challenge.

Why has this been such a long process?

It is mainly because we realised our initial theory wouldn’t work and then had to determine why it wouldn’t work and devise solutions to make it right. We then had to test out the new ideas and confirm they worked. This was a complex process, and each step took several years to complete.

Aside from the challenge of the cap, what other difficulties did you face and how were these overcome?

The challenges are threefold – overcoming technical issues, securing resources, and battling with inner doubt.

When it comes to the technical side of things, we are fortunate to have a good team. Originally, we nominated the 20-people team for the John Dawson Award, but we had to narrow this down to just five. Over the last two decades, we have built a community of students and visiting scientists who have collaborated with us and made strong contributions to the project. The expertise of our team members and community has helped us to overcome the technical challenges we faced.

Financially, we have had to send numerous funding proposals to our funding agencies – National Science Foundation (NSF), NASA, and the U.S. Department of Energy – for support. Whilst these proposals were sometimes unsuccessful, we were able to secure funding for each of the steps. Additionally, the lab here at PPPL is also very supportive.

The third challenge is more psychological. Over the years, we have asked ourselves several times about the experiment. Is it really worth the effort, time, and money? Is it the right problem to focus on? We had to make a value judgement and persevere.

What does it mean to you to be recognised by the John Dawson Award?

It is a huge honour to be recognised for our efforts by the scientific community. Thousands of scientists around the world work day and night in our field, so it is a tremendous honour to be chosen to receive this award. Our group is very small compared to the whole community, so we really appreciate that the value of our contribution has been recognised. After all, small does not mean unimportant and we expect there to be several implications from our work.

Receiving the award also highlights the importance of not giving up. You must remain persistent and be patient with yourself and your peers. It may take some time to see results, but giving up could mean missing out on a big opportunity.

Do you have a final message that you would like to highlight?

I want to stress the importance of supporting basic research, as it can improve our understanding of the Universe and things around us. Each small project is a building block towards tomorrow’s technology. The commercial world wants results today, but it is crucial to support longstanding research to make tomorrow’s tomorrow better.

Please note, this article will also appear in the 25th edition of our quarterly publication.