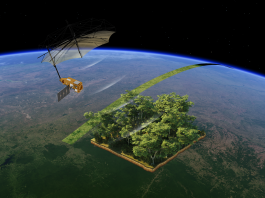

Every day, Earth is bombarded by objects from above – not just natural space rocks but a growing cloud of human-made debris.

Space junk, such as defunct satellites, broken rocket parts, and even tools dropped by astronauts now orbit our planet at speeds of up to 18,000 miles per hour, posing a persistent threat both in space and back on Earth when they re-enter the atmosphere.

While most of it burns up harmlessly in the atmosphere, larger fragments of space debris can survive re-entry and crash to the ground.

Now, scientists are turning to an unexpected source – inaudible sound waves – to better detect and predict these fiery re-entries.

New research reveals how infrasound technology could play a pivotal role in tracking space debris, improving global safety and planetary defence.

Space debris and re-entry challenges

As the cloud of space debris grows, so does the frequency with which fragments fall back to Earth. Predicting where these fragments or natural meteoroids will land is a high-stakes challenge.

Objects entering Earth’s atmosphere can either plummet vertically or travel in at a shallow angle, skimming through the atmosphere before crashing down. Accurately forecasting their landing zones is crucial to avoiding damage or casualties.

Listening to the sky with infrasound sensors

In an effort to improve prediction models, a new study led by Elizabeth Silber of Sandia National Laboratories is shedding light on how infrasound – a type of low-frequency sound wave imperceptible to humans – can be used to track space debris.

These infrasound signals are produced when high-energy events such as bolides (bright flashes from meteoroids disintegrating in the atmosphere) occur. They generate shock waves that ripple through the air for thousands of kilometres.

Using a global network of infrasound sensors maintained by the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO) – originally intended to detect nuclear explosions – Silber analysed how these instruments could also be repurposed to detect and track the trajectory of falling space debris.

Shallow angles, greater uncertainty

The study, which will be presented at the upcoming General Assembly of the European Geosciences Union, highlights a key challenge: when space debris or meteoroids enter the atmosphere at a steep angle (greater than 60 degrees), infrasound analysis can accurately track their path.

However, when objects enter more horizontally, interpreting the data becomes significantly more complicated.

The sound is not generated at a single point but continuously along the object’s flight path – much like an extended sonic boom across the sky.

This movement confuses traditional trajectory models, especially when different infrasound stations detect sounds from varying directions. The research emphasises the importance of accounting for this motion to improve prediction accuracy.

Enhancing planetary defence

The findings carry significant implications for planetary defence and public safety. As the volume of space debris increases, so does the risk of uncontrolled re-entries over populated areas.

Improved detection methods, like those involving infrasound sensors, could lead to faster, more reliable predictions about where space junk might land – allowing for better emergency preparedness and possibly even targeted mitigation.

In the era of expanding satellite constellations and renewed interest in space exploration, understanding and managing space debris isn’t just about cleaning up orbit. It’s about protecting the people below.