The University of Mississippi’s Professor Breese Quinn discusses a wider picture of multimessenger astrophysics, which includes muons as a messenger for studying the fundamental nature of spacetime.

Multimessenger astrophysics is widely defined as the field of research wherein observations of electromagnetic radiation, high-energy neutrinos and cosmic ray particles, and gravitational waves emanating from the same cosmic events are studied in concert to yield a comprehensive understanding of astrophysical processes. Light has been used to learn about the cosmos as long as people have looked up at the stars in the sky. Astroparticle physics traces its beginnings to Victor Francis Hess’s balloon flights in the 1910s, which resulted in the discovery of cosmic rays. Gravitational waves were first detected by the LIGO/Virgo collaborations in 2015, with the observation of the binary black hole merger GW150914. Supernova SN 1987a, viewed first with neutrinos and hours later with optical light, was the first astrophysical event observed with multiple messengers. However, multimessenger astrophysics truly emerged as a distinct, fully integrated field when gravitational waves from the neutron star collision GW170817 were closely followed by corresponding measurements across the electromagnetic spectrum.

A broader view of multimessenger astrophysics

The definition of multimessenger astrophysics articulated above is quite clear and precise, focused on the study of sources of a specific set of multiple messengers which deliver complementary information, revealing the physical processes associated with those cosmic events. A somewhat broader view of multimessenger astrophysics could also include the use of some of these same messengers and others to probe the fundamental structure of spacetime itself by analysing the details of their passage or propagation through the universe. In other words, are the different messengers’ journeys through the cosmos sensitive to possible aspects of spacetime structure that may be directly measurable by experiment?

A historical analogy may be illustrative here. It was clearly important that Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery Expedition delivered on their primary mission by confirming that a transcontinental Northwest Passage did not exist. But arguably, the most valuable product of that endeavour was the detailed observations of the journey itself, recorded in their maps and journals. It is important that we fully investigate the fundamental nature of the spacetime through which we travel using the full suite of messenger probes available to us.

Using muons as probes of spacetime symmetry

For good reason, muons are not considered a primary component of multimessenger astrophysics. With a lifetime of 2.2 µs, any muons produced in a distant astrophysical event would decay long before travelling any significant cosmic-scale distance. However, muons contained in a storage ring experiment on Earth are sensitive to effects that would be produced by various new physics scenarios associated with the spacetime environment, including Charge-Parity-Time reversal (CPT) and Lorentz Invariance Violation.

A branch of physics dedicated to the study of spacetime symmetries searches for violations of the symmetry of combined CPT transformations, which is fundamental to quantum field theory, as well as violations of Lorentz Invariance, which is foundational to relativity theory.1,2 The Standard Model of particle physics does not include any interactions that allow CPT and/or Lorentz Invariance violation (CPTLV). CPTLV terms can be added to the Standard Model, however, and these terms predict specific measurable effects for different particles, including muons. Chief among these effects on muons are impacts on the measured value of the anomalous magnetic moment of the muon, known as muon g-2.³ Muon g-2 essentially represents the complexity of a muon’s interaction with a magnetic field.

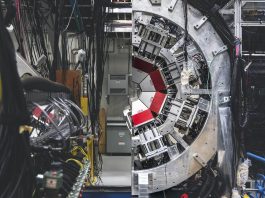

The Muon g-2 Experiment at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab), shown in Fig. 1, collected data from 2018 to 2023 and is nearing completion of the data analysis, with a design goal of measuring g-2 with a precision of at least 140 parts per billion. A measurement that precise could help discriminate between competing methods of theoretical calculations or possibly lead to the discovery of new physics. The news of Muon g-2’s preliminary 2021 result, based on roughly 10% of the data, reached an estimated audience of more than 6 billion people,4,5 and the experiment’s full data set measurement is one of the most highly anticipated results in the last decade of particle physics.

But there is more physics to be gleaned from Fermilab’s Muon g-2. One predicted effect of CPTLV on muons in a storage ring experiment is a sidereal oscillation in the value of g-2. This is because Lorentz Invariance violation is equivalent to a preferred direction in space caused by the existence of a uniform background vector field in the cosmos. As the muons in the storage ring rotate relative to that field (e.g. by the spinning of the Earth on its axis relative to the background stars), the strength of the interaction between the muons and that vector field would vary corresponding to the orientation of the muon’s spin axis relative to the vector field direction, resulting in an oscillation in the value of g-2 at the sidereal rotation frequency. The muons’ journey through spacetime would reveal details of its fundamental structure. Additional CPTLV signatures in muon g-2 would be differences in the value of muon g-2 measured with negative vs. positive muons.

Muons and dark matter

A critical yet unknown component of the spacetime environment is the identity and nature of dark matter. Dark matter accounts for 85% of all the mass in the universe and nearly 27% of the total mass-energy, but its particle nature remains a mystery. There are myriad candidates ranging in mass over fifty orders of magnitude, from a trillion trillion times lighter than an electron (10-23 eV) to one milligram (1030 eV, about the mass of a mosquito). Ultralight dark matter candidates are so light that other particles would interact with them as if the dark matter were a coherent wave-like background field rather than individual particles. This type of dark matter would function as part of the background structure of spacetime.

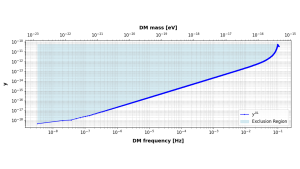

Ultralight muophilic dark matter is a particular dark matter candidate that interacts most strongly with muons and has an extremely low mass. Time series analysis of muon g-2 data could reveal the presence of two different forms of ultralight muophilic dark matter: one with relatively simple interactions (scalar), and one with somewhat more complex interactions (pseudoscalar).⁶ The scalar version would manifest as an oscillation in the value of g-2, but with a frequency equivalent to the mass of the dark matter particle rather than at the sidereal frequency associated with CPTLV. Fig. 2 shows a Monte Carlo study of the Fermilab Muon g-2 experiment sensitivity to this scalar dark matter as a function of the dark matter mass/frequency. The pseudoscalar version is identified by time-dependent vertical variations in the g-2 data from the horizontal storage ring. In both cases, the dark matter is detected by moving the muon messengers through spacetime and recording the details of that journey.

matter as a function of mass/frequency. y is in dimensionless units, e.g. y=10-12 represents a one part in a

trillion effect.

Mississippi’s role with multimessenger muons

At the University of Mississippi Center for Multimessenger Astrophysics (UMCMA), we are engaged in each of the three ‘core’ areas of multimessenger studies. The Blazar group models and examines observations of electromagnetic radiation from powerful jets of relativistic plasma emanating from supermassive black holes, with their investigations spanning the entire electromagnetic spectrum from radio waves to gamma rays.

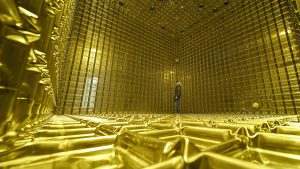

The Gravity group focuses on binary black hole and neutron star systems through theory and observation, including the development of mathematical models of black hole ringdown and work on detection and parameter estimation for the LIGO Collaboration and the LISA Consortium. The Neutrino effort within UMCMA collaborates on the NOvA and DUNE experiments, both of which are designed to observe supernova neutrinos in addition to the main oscillation measurements of beamline neutrinos.

In the broader view of multimessenger astrophysics that encompasses the study of the nature and structure of spacetime, UMCMA plays a unique role using muons as a messenger, not as a messenger sent to us from somewhere else, but rather as a messenger sent out on a mission to gather information and bring it back. It does this through collaboration on the Fermilab Muon g-2 experiment. The Mississippi Muon g-2 group is deeply involved in the main g-2 measurement of the experiment, but Mississippi is also the sole institution performing the searches for CPTLV and dark matter in the g-2 data. Our g-2 searches for CPTLV will have discovery sensitivity, and at the very least will produce the best and/or new limits on almost all CPTLV terms in the muon sector.

In addition, this group plans to carry CPTLV studies over to DUNE, searching for these symmetry violations in the neutrino oscillation data as well as in the time structure of supernova neutrino propagation through space, which could provide evidence of a foamy quantum gravity nature of spacetime.⁷ The two dark matter analyses of Muon g-2 data represent the first ever direct search for dark matter in a muon storage ring. All these spacetime studies represent opportunities for students in Mississippi to make unique contributions to multimessenger astrophysics and further our understanding of the cosmos.

References

- D. Colladay and V. A. Kostelecký, ‘CPT Violation and the Standard Model.’ Phys. Rev. D 55, 6760 (1997)

- D. Colladay and V. A. Kostelecký, ‘Lorentz-Violating Extension of the Standard Model.’ Phys. Rev. D 58, 116002 (1998)

- R. Bluhm, et.al. ‘CPT and Lorentz Tests with Muons.’ Phys. Rev. Lett. 84 (2000) 1098.

- B. Abi et al. [Muon g-2 Collaboration], ‘Measurement of the Positive Muon Anomalous Magnetic Moment to 0.46 ppm.’ Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, no.14, 141801 (2021)

- https://news.fnal.gov/2021/04/first-results-from-fermilabs-muon-g-2-experiment-strengthen-evidence-of-new-physics/

- R. Janish and H. Ramani, ‘Muon g-2 and EDM experiments as muonic dark matter detectors.’ Phys. Rev. D 102, 115018 (2020)

- A. Kostelecký and M. Mewes, ‘Lorentz and CPT violation in neutrinos.’ Phys. Rev. D69 016005 (2004)

Please note, this article will also appear in the 22nd edition of our quarterly publication.