How the world’s largest machines unravel the behaviour of (anti-)matter’s fundamental building blocks.

Antimatter was just as abundant as normal matter in the very early Universe, just after the Big Bang. Antimatter is almost the same as matter, just with opposite charges. And so, when antimatter and matter meet, they annihilate each other to leave nothing but energy. Such annihilation is what almost the entire early Universe underwent. What we can now observe as planets, stars, and galaxies is a tiny portion of leftover matter, while all antimatter has vanished. This tiny, yet so vital, matter-antimatter asymmetry is the reason for the existence of the Universe as we know it. Nevertheless, a deeper understanding of this asymmetry evades us, and it is one of the most fundamental questions particle physicists, such as Professor Gersabeck, seek to unravel.

For decades, particle physicists have studied the behaviour of the fundamental building blocks of matter. They use the collisions of particles that have been accelerated in machines of ever-increasing size to produce their particle of interest. Sometimes these are of similar mass to the original particles that travelled through the accelerators. But following Einstein’s energy-mass equivalence expressed through E=mc², high-energy particle collisions can produce new, massive particles such as the Higgs boson that was discovered in 2012 in the collisions of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN. The LHC, boasting a 27 km circumference, is the world’s largest machine and is equipped with four major experiments, surrounding the points where particles are brought to collision.

The physics of flavours

The fundamental building blocks of protons and neutrons, which make up atomic nuclei, are the so-called quarks. These cannot exist as free particles but can also form other bound objects, some of which contain a quark and an antiquark. There are six different quarks, called flavours, named up, down (those two make up protons and neutrons), charm, strange, top and bottom (or beauty). The top quark is heavier than a tungsten atom and decays into lighter particles before it can form a bound particle. The other three less common flavours, charm, strange and beauty, form bound particles that can be produced in collisions. When these quarks match up with antiquarks, they form superb laboratories for studying matter-antimatter asymmetries. This is at the heart of what is called flavour physics.

Professor Gersabeck’s group at the University of Freiburg in Germany is one of the newest additions to the approximately 100 institutes that form the LHCb collaboration. Together, they built and now operate the LHC-beauty (LHCb) experiment, which is one of the four major LHC laboratories. This purpose-built flavour physics experiment was designed to study predominantly particles containing charm or beauty quarks. Having operated initially from 2010 to 2018 and now again after a major upgrade to most of its subsystems, it has established itself as the leading player in the field of flavour physics. Professor Gersabeck moved to Freiburg in 2024, having previously led one of the largest LHCb teams at the University of Manchester, UK.

The LHCb experiment can already look back on a track record of numerous discoveries and groundbreaking measurements, including several in the area of matter-antimatter asymmetries. This includes the first time such an asymmetry was ever observed in the decay of a particle containing a charm quark. Professor Gersabeck is one of the longest-standing LHCb members to work on charm physics. This discovery completed a set after matter-antimatter asymmetries had previously been observed in particles with strange quarks (first in 1964) and with beauty quarks (first in 2001), each of which led to the award of a Nobel Prize.

Most of the matter-antimatter asymmetries observed to date can be explained within a mechanism that was postulated already in 1973, and which still is an integral part of what is called the Standard Model of particle physics. However, these asymmetries are by far insufficient to explain the matter dominance in the Universe. Therefore, the hunt is on for new sources of asymmetries, which would be connected to new particles from beyond the Standard Model.

Quantum effects

New particles, which may be much heavier than all known particles, can influence the decays of Standard Model particles through quantum mechanical effects. Such effects can lead to a changed rate of decay, altered angular distributions of the decay products, or lead to new matter-antimatter asymmetries. The observation of one such effect can be an unambiguous proof of physics beyond the Standard Model. But it is the combination of several observations of new effects that can pin down the nature of these new particles.

Historically, flavour physics has demonstrated this path to discovery through quantum effects several times. In the early 1960s, only the up, down and strange quarks were known. The absence of an observation of a specific strange particle decay led to the postulation of the existence of a fourth quark, charm. Even before this was discovered, the discovery of matter-antimatter asymmetries led to two further quarks, top and beauty, being predicted. With similar techniques, flavour physicists nowadays seek to discover quantum imprints of new particles in measurements that are carried out with much greater precision compared to what was possible in the last century.

The prediction of the top quark came over 20 years before it was discovered. Its mass had meanwhile been predicted, against expectations, to be much heavier than that of the other quarks, based on the result of another flavour physics measurement. This measurement studied the rate at which neutral particles containing a beauty quark oscillate into their antimatter mirror image and back. Such oscillating particles are a prime laboratory for studying matter-antimatter differences and are the focus of the research of Professor Gersabeck and his group.

Charming puzzles

The matter-antimatter asymmetry in charm decays, which was discovered by the LHCb experiment in 2019, cannot be explained by the asymmetry in the Standard Model in a straightforward way. Some theoretical estimates indicate an asymmetry that is about an order of magnitude smaller than what has been measured by LHCb. However, not all assumptions could thus far be tested to a degree that rules out an explanation within the Standard Model.

The puzzling situation of the origin of the matter-antimatter asymmetry in charm decays has opened up a new research field. Three roads promise to elucidate this window into the antimatter world. The first are higher precision measurements of the observed asymmetry. This includes both new measurements by LHCb and measurements by other experiments; however, no experiment in existence is expected to be able to surpass LHCb’s precision. A confirmation of the effect with greater precision will pinpoint the magnitude of the potential discrepancy with the Standard Model.

The second road is measurements of complementary decays of charm particles. Some of these are known to be largely immune to effects from beyond the Standard Model and can hence provide a benchmark to compare against. Others have varying degrees of sensitivity to the influence of new particles through quantum effects. Observations in these measurements would facilitate a more precise identification of the type of new particles. This is a road that Professor Gersabeck’s group has been pursuing for several years, so far without a clear sign of a new asymmetry.

The third road is the search for asymmetries related to the aforementioned matter-antimatter oscillations of neutral particles. The asymmetry expected within the Standard Model is unmeasurably small, rendering any non-zero measurement a discovery of physics beyond the Standard Model. These measurements have also been a long-standing focus of Professor Gersabeck’s group.

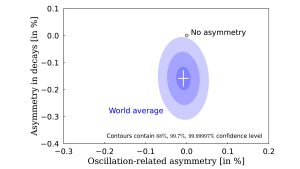

The ultimate precision is achieved by the statistical combination of measurements from all relevant experiments worldwide. This combination is performed by the Heavy Flavor Averaging Group in which Professor Gersabeck co-leads the charm asymmetry section. The figure below shows how current asymmetries point to an effect in decays only.

Real-time precision

Measurements in particle physics are based on many observations of the same phenomenon, which reduces the statistical uncertainty, typically with the square root of the number of observations. This implies that ever greater data sets need to be accumulated; and, to do this in a finite amount of time, they need to be accumulated with ever-increasing collision rates. This presents a formidable challenge both for the detection systems and for the data acquisition and processing infrastructure.

Currently, the full LHCb detector, 20m of high-precision systems, is read out 40 million times a second, once every time collisions can happen in the LHC. This requires that the sensitive elements be able to perform their measurements and transmit their signals within 25 nanoseconds. For every collision, the LHCb detector has to trace hundreds of particles and identify interesting particle decays among the plethora of additional, largely unrelated particles. This amounts to a data rate of 40 Terabits per second that has to be processed in real time, corresponding to about 4% of the global internet bandwidth in 2022.

One of the most innovative parts of the LHCb experiment is its real-time data processing scheme. For the first time in a particle physics experiment, the processing is fully software-based, which massively increases flexibility and precision. In a first stage, interesting signatures are identified by a network of over 300 Graphics Processing Units. The collisions of interest are stored on a disk buffer while the full detector is calibrated, such that the subsequent selection can proceed with the highest data quality. This calibration is currently under the responsibility of Professor Gersabeck’s group. The final selection, performed on Central Processing Units, produces an output of 80 Gigabits per second, which are stored permanently for subsequent analysis.

Future opportunities

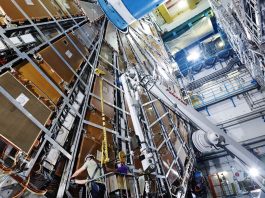

A further increase in the collision rate is planned for the mid-2030s to facilitate another step change in precision. This so-called LHCb Upgrade 2 will further push the boundary of what is technically feasible to improve what can be resolved in existing measurements and to open up new measurement opportunities. Professor Gersabeck’s group is actively involved in developing new solutions for the largest particle tracking detector of the LHCb experiment.

Having previously, while at Manchester, been responsible for the construction of the comparatively small detector modules that now surround the collision point, Professor Gersabeck now works on a two-technology detector covering an active area of nearly 100 square metres. His group is involved both in the part that uses sub-millimetre thin scintillating fibres (similar to those used in the current detector modules shown in the photo below next to the beam pipe) and in exploiting silicon pixel sensors.

In addition to enabling answers to very fundamental questions, the technology, from sensors to data acquisition hardware, and processing and analysis algorithms, regularly facilitates serendipitous applications in many other fields. There are many knowledge exchange pathways involving areas such as medical imaging and security applications. Similarly, particle data experts often find their skills in use to big data challenges across the globe.

As such, the field is an extremely versatile training ground for generations of highly skilled physicists. Working in a group with a variety of involvements also enables students and early career researchers to experience this breadth and to further their interests and strengths, whether these lie in the development of new devices or the latest application of artificial intelligence opportunities. Such work is only possible through a concerted, collaborative effort in multi-disciplinary teams involving all from students to professors, engineers and technicians. Along the way, countless discoveries remain to be made in the understanding of the mysterious quantum world of antimatter.

Please note, this article will also appear in the 23rd edition of our quarterly publication.