The world’s longest thermometer takes the temperature of extreme matter.

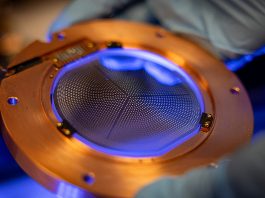

When we measure temperature in everyday life, we use a thermometer. When scientists need the temperature of matter driven to extremes, for example, when replicating conditions inside planets, fusion capsules, or laser-stressed metals, they use something much larger: a 3km X-ray laser.

At SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California, the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) produces ultrabright, ultrafast X-ray flashes that can track atomic motion directly. In this sense, it acts as the world’s longest thermometer, a beam of X-rays that records a reading in the instant a short-lived, highly excited state of matter is created.

These experiments operate on timescales that are difficult to grasp. Processes that would blur together at ordinary speeds are resolved here using trillionths-of-a-second X-ray pulses, on the order of picoseconds. No physical probe can be inserted into such a brief event, so the light itself serves as the thermometer and effectively turns LCLS into a kind of radar gun for atoms.

How do you take the temperature of a trillionth-of-a-second event?

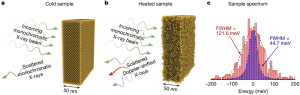

The basic idea is straightforward to describe, even if it is technically demanding to carry out. First, a femtosecond laser delivers a controlled energy pulse to a thin metal foil, setting its atoms into rapid motion. A precisely timed X-ray pulse then scatters from those atoms and returns with a small Doppler broadening, a slight shift in energy (or ‘colour’) caused by their motion. By measuring that broadening, we infer the atomic speeds, and from those speeds we determine the temperature. This provides a direct, in situ measurement at the moment when the extreme state exists. At the same time, we record a diffraction pattern to confirm that the crystal lattice remains intact, so the extracted temperature can be assigned to a solid at that instant.

Two aspects are crucial. The first is timing: the heating pulse and the X-ray probe are separated by only a few trillionths of a second, so we observe the system while it is still hot, before it can cool or structurally relax. The second is precision. The X-ray energy is measured with very high resolution, so even a small Doppler broadening can be resolved. The atomic motion is encoded directly in the scattered light, which removes the need to rely on indirect assumptions about what is happening inside the material.

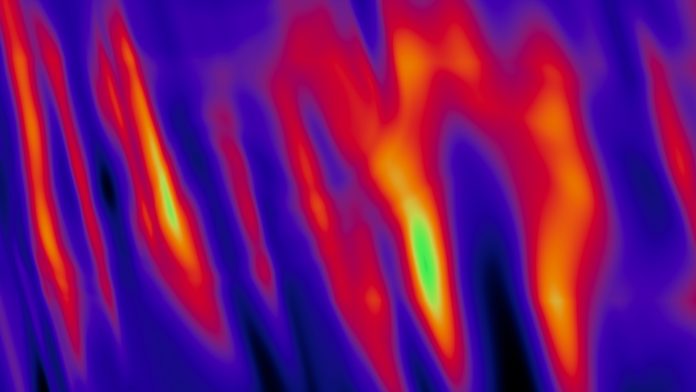

The ‘longest thermometer,’ in plain English

In simple terms, this relies on the Doppler effect. When a siren moves towards you, its pitch sounds higher; when it moves away, it sounds lower. X-rays scattered from vibrating atoms behave in an analogous way, not through a large shift in pitch, but through a slight shifting of their frequency (or energy). Hotter ions move faster and produce a broader spectrum, so the width of that blur provides a direct measure of their temperature. This is exactly what happens in the experiment: the hotter the ions, the broader the blur in the measured spectrum.

The surprise: a solid that stays solid at ~19,000 K

Using this light-as-thermometer method, the team pushed a gold crystal into a regime that was previously considered unlikely: roughly 19,000 kelvins, about 14 times gold’s equilibrium melting temperature, while the crystal lattice remained intact.¹

For decades, prevailing models suggested that solids would not remain stable much beyond about three times their melting temperature before encountering an ‘entropy catastrophe,’ a rapid loss of crystalline order as vibrations disrupt the lattice. The new results show that, if the heating is fast enough, the material can temporarily avoid this collapse during the brief interval probed by the X-ray pulse.

The key factor is the rate of energy deposition. The crystal is heated so quickly that it has no time to expand, flow, or structurally fail. For a very short time, crystalline order persists in conditions that straightforward equilibrium arguments would rule out, providing a new view of how melting begins when a material is driven far from equilibrium.

The superheated solid exists only transiently, but that is sufficient. The measurement captures a well-defined snapshot of the system at extreme temperature and confirms that the temperature can be determined directly in this short-lived, still-solid state.

Why this matters

High-energy-density (HED) matter sits between familiar solids and fully ionised plasmas. Examples include planetary cores, shock-compressed metals, and fusion fuel on the way to ignition. In many of these systems, pressure and density are reasonably well constrained, but historically, temperature has been much harder to measure directly.

The measured broadening of the scattered X-rays provides a direct temperature diagnostic from atomic motion. This reduces reliance on indirect models and allows more stringent tests of how heat flows, how electrons and ions exchange energy, and how crystals approach melting under extreme drive.

the ‘world’s longest thermometer’ in these experiments. Credit: U.S. Geological Survey Department of the Interior/USGS

With high-repetition X-ray lasers, the same approach can be used to map temperatures during shock compression and in fusion experiments where ion temperature is a key parameter. The resulting data can then be used to obtain quantitative measurements that benchmark and refine our understanding of matter at high energy density. Together, these capabilities turn short-lived HED states into quantitative testbeds for theories of matter far from equilibrium.

A milestone and a starting line

This work delivered two milestones at once: the first direct, in situ reading of atomic temperature in these extreme solids, and, as far as we know, the hottest crystalline material yet recorded. It also challenged a long-standing expectation about how far superheating can go before a crystal loses its order.

More importantly, it opens a set of new questions that can now be addressed with direct measurements:

- How does a crystal actually fail under this kind of drive? Does it unravel from defects or give way more uniformly?

- How quickly does heat move between electrons and ions when both are far from equilibrium?

- Which materials remain ordered the longest under ultrafast drive?

- Can that resilience be used in applications?

The method itself is broadly transferable. It relies on an intense, well-characterised X-ray pulse and a high-resolution spectrometer, ingredients that are available at several X-ray free-electron lasers around the world. As a result, the same temperature diagnostic can be applied across many experiments that probe melting, heat transport, and material stability under extreme conditions.

High-energy-density science, more generally, is about creating, controlling, and diagnosing states of matter that are difficult or impossible to access in ordinary settings. Giant lasers drive shocks that resemble those in astrophysical explosions, diamond anvils compress materials to planetary pressures, and X-ray lasers allow us to follow atomic motion in real time. This work adds a quantitative thermometer to that toolkit. It shows that temperature can be measured directly in an ultrafast, far-from-equilibrium solid at the same time as its structure is confirmed.

In the process, the team also set a practical benchmark for how hot a crystalline solid can be driven while remaining ordered. The record itself is secondary, but it illustrates what is now possible. Materials can be driven to conditions that once seemed out of reach, and their response can be measured with precision. That is how the field advances: by turning increasingly extreme regimes into carefully characterised experiments.

References

- G. White et al., “Superheating gold beyond the predicted entropy catastrophe threshold,” Nature 643, 950–954 (2025)

Please note, this article will also appear in the 25th edition of our quarterly publication.