The ANEMEL project has recently achieved major breakthroughs in its plight to sustainably produce green hydrogen from low-quality water sources.

Green hydrogen holds great potential in the journey to net zero. However, traditional production methods for this can prove lengthy, costly, and inefficient. Now, researchers are exploring new methods to produce green hydrogen from low-quality water sources, such as seawater and wastewater.

Funded by the European Innovation Council and led by the University of Galway, in Ireland, the ANEMEL project aims to develop efficient electrolysers powered using renewable technologies. The electrolysers will utilise non-critical raw materials within all their basic components, including electrocatalysts and membranes. All this will reduce the cost of the electrolyser components and improve their recyclability, thus reducing waste and providing a competitive advantage.

Whilst the project is led by the University of Galway, it also works in close partnership with researchers from nine organisations across Europe. Recently, with the help of its partners, the project has hit several important milestones in its journey to achieving more cost-effective, sustainable and efficient hydrogen production. To find out more, we spoke to ANEMEL Coordinator Dr Pau Farràs.

Can you explain more about the ANEMEL project and its main objectives?

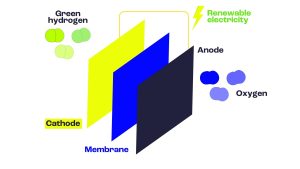

The goal of ANEMEL is to develop a water electrolyser – an instrument that breaks down water into oxygen and hydrogen using electricity. This is a critical pathway for the hydrogen economy because, although there are other types of technologies that can be used to obtain hydrogen, a water electrolyser can be coupled to renewable energy to produce hydrogen with no carbon emissions.

Many companies are commercialising water electrolysers, and there are different types – depending on the operation and their components. A water electrolyser is not something new, with some operations dating back as far as 100 years. One of the main issues with water electrolysers is that some of the commercial ones use strong bases, such as potassium hydroxide or sodium hydroxide, at high concentrations, which are corrosive and hazardous. Building large plants, therefore, becomes a significant health and safety concern. Conversely, the newer polymer electrolyte membrane (PEM) electrolysers need ultra-pure water to run. In both cases, the water must be purified to the highest level possible to ensure stable electrolysis.

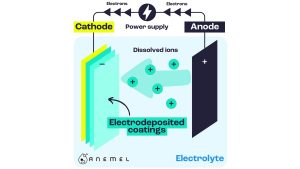

ANEMEL aims to develop the components that go into an electrolyser (electrodes and membranes) to be compatible with impurities in water. We are doing this through a stepwise approach of increasing the challenging aspects of the operation.

Typically, available anion exchange membrane (AEM) electrolysers operate using concentrated solutions of potassium hydroxide. Whilst this is not as bad as the old alkaline electrolysis, it is still something that should be avoided. In ANEMEL, the first challenge is to reduce the concentration of potassium hydroxide to, in turn, reduce the hazardousness and corrosiveness of the electrolyser. This will make it easier and cheaper to operate.

The second stage is to operate the electrolyser under the same conditions as a PEM electrolyser. The issue with PEM electrolysers is that they require the use of precious metals – such as iridium, ruthenium, and platinum – which are very expensive. To achieve large-scale hydrogen production, you will need to use a lot of these precious metals that are not very abundant. In the case of the anion exchange membrane, you can use cheaper and more abundant metals, but they need to be built up in a way that they can be used under the conditions of ultra-pure water, mimicking the operation of the precious metals.

The last step is working with impure water. The way that we define impure water in our case is by adding salt. We have a concentration of salt that is very similar to that of oceans. The idea is that a lot of the impure streams, or water streams that would not be competing with drinking water (e.g. sea, ocean, wastewater), contain salts. We want to show that we can operate this electrolyser under salty conditions.

There is a specific reason why we have chosen to focus on improving AEM electrolysers over PEMs. Salt is sodium chloride and, when you have chloride in the electrolyte in the water, the reaction of oxidising water molecules will compete to the oxidation of chloride ions to chlorine, which is a corrosive gas that will destroy the components of the electrolyser. To avoid this reaction and minimise the risk, we must operate at pH neutral to basic. If you want to operate a PEM electrolyser under acidic conditions, the difference between oxidising chloride ions and oxidising water is extremely small. This does not leave much leeway on the operation because, if you make a mistake or have some degradation of your catalyst, you will be very easily oxidising the chloride to chlorine gas instead of the reaction that you want to happen. This is why we are operating under these AEM conditions, as opposed to PEM.

In summary, we want to develop electrolysers that are more robust than those currently available on the market. The only way that we can achieve clean hydrogen production prices that compete with hydrogen produced using fossil fuels is by developing electrolysers that are very robust and long lasting. In addition, it is important to develop components that are less susceptible to decomposition to elongate the lifetime of these technologies.

Can you highlight some recent achievements from the project?

In terms of the electrolyser, our main objective is to develop an electrolyser that has a power of 1kW. In order to have a 1kW electrolyser that is producing enough green hydrogen, we needed to design the different parts of the electrolyser so that we could achieve this at a very high efficiency. To do this, our partner from the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Switzerland designed a 1kW unit and, using simulations, then managed to find the right configuration to optimise the operation to have very good efficiency.

The team at EPFL simulated a 1×1cm² membrane electrode assembly (MEA) based in commercially available materials, already proven viable. A MEA is formed in layers, like a sandwich. The middle is a membrane, coated with a catalyst on each side. The membrane separates the hydrogen and oxygen gases produced during the electrolysis process. The catalysts accelerate the electrochemical reactions – each side-reaction requires different materials, specific for hydrogen and oxygen evolution.

The researchers created this computational model considering certain simple parameters, such as membrane thickness or temperature. Among other things, the team discovered that pH was the most influential parameter in the performance of these electrolysers. The results from the study of the simulated membrane electrode assemblies were published in a peer-reviewed paper.

We also made progress in relation to the stack element of the electrolysers. A stack is composed of different cells and, in the case of these electrolysers, five cells make a stack. With multiple-cell modules, you can produce more hydrogen by adding more cells or stacks. To study the components that go into each cell, instead of looking at the whole stack, you can take just one cell and study its operation and the components. Alongside our partner researchers in TU Berlin, in Germany, and the EPFL, in Switzerland, we did this by operating a single-cell system under salty conditions.

In another significant achievement, the EPFL group led by Professor Xile Hu were able to demonstrate the operation of the anion exchange membrane water electrolyser (AEMWE) system using pure water at very high current densities, leading to greater hydrogen production. This is one of the main advantages over the 100-year-old technology which operates at very small current densities – meaning that, for the same amount of hydrogen produced, you need much bigger volumes and areas of the technology. The study, published in Angewandte Chemie, demonstrated AEMWEs operating at an ultrahigh current density of 10 A/cm² for over 800 hours, without a decrease in performance. In comparison, state-of-the-art benchmark electrolysers only sustain such current densities for a few seconds. This represents an impressive 500,000-fold increase in performance.

Our team has also been working on the design of the electrocatalysts – components that sit alongside the membranes. Electrodes in the AEMWE stack represent a considerable share of the overall electrolyser cost. Therefore, a lot of research is going into the development of new, efficient, and cost-effective catalysts for the electrodes that can function well in an alkaline environment, leading to a reduction in expenses and improved performance.

What are your main priorities for the year ahead?

So far, we have predominantly been operating at lower hydroxide concentration than conventional AEMWEs. Our priority for the rest of the project is to have the stack operating using pure water and salty water. We are focused on continuing the development of the electrocatalyst and the membrane so that they can operate under these conditions.

In addition, when you go from the single cell to the stack level, you need to start producing more quantities. We must therefore scale up the most active catalyst and the best membranes, which we are in the process of doing now. Instead of producing mg-scale of a catalyst and cm²-scale of membrane, we need to go for tens of grams of catalyst and square meters of membranes. This scale-up process requires thorough research and development so that our processes can be scaled up and are compliant with the circularity of the different components that we want to produce.

How important is collaboration in your work?

Collaboration is critical because, as you have seen, there are different components and it is impossible for one single group or organisation to cope with everything. With any electrolyser manufacturer, in most cases their expertise lies in assembling the components that they have bought from elsewhere. They are not developing everything from scratch, as a wide range of skills and know-how is needed. Collaboration with different experts from various institutions is the only way that you can make this happen.

Our partnerships with companies on the project are very beneficial when it comes to the scale-up because of the expertise they have gained from scaling up previous products. Their input on how we should scale up, as well as helping to bridge the gap between academia and industry, is imperative.

Please note, this article will also appear in the 22nd edition of our quarterly publication.