Scientific data on the atmospheric re-entry process of satellites is urgently needed to ensure a quick, safe, and sustainable demise at the end of their mission, reducing risks on the ground and in space.

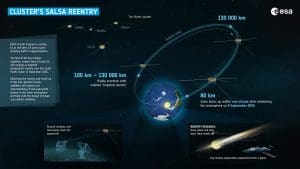

The European Space Agency (ESA) has now successfully manoeuvred its remaining two Cluster satellites to ensure that its atmospheric re-entry data can be recorded from a plane as they return to Earth orbit later this year.

“Moving two satellites to meet a plane sounds extreme, but the unique re-entry data we’ll collect is worth orchestrating the challenging encounter over a remote stretch of ocean,” explained Beatriz Jilete, space debris systems engineer at ESA.

Why atmospheric re-entry data is urgently needed

Understanding how satellites fall through the atmosphere is crucial to helping build safer, more sustainable spacecraft and reduce the risk of falling debris from space.

“With better data on exactly when and how they heat up, break up, and which materials survive, engineers can design satellites that burn up completely, so-called design-for-demise satellites,” said Stijn Lemmens, Draco project manager at ESA.

However, atmospheric re-entry is difficult to witness up close because of its violent nature and the hard-to-reach altitude of around 80 km in the upper atmosphere.

Re-entries occur too high for balloon-based observations or satellite-based sample collection, and satellites in orbit are too far away to see much. Normally, re-entry locations are too unpredictable to observe from the ground or the air.

The Cluster satellites present an opportunity to this challenge

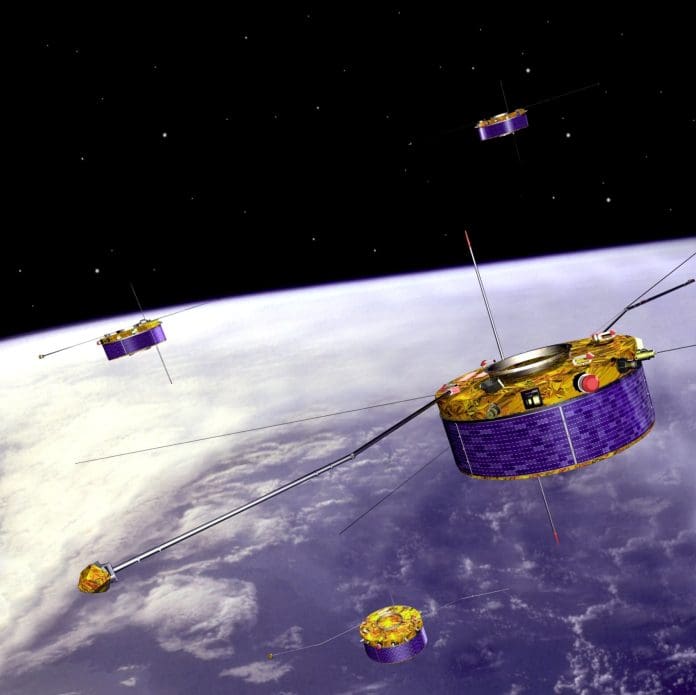

With the Cluster quartet’s ‘targeted re-entries’, ESA is setting a precedent for a responsible approach to reducing the ever-increasing problem of space debris and uncontrolled re-entries, also from less commonly used orbits.

It shows that older missions can be disposed of in safer and more sustainable ways than was thought possible at the time of design.

Jilete stated: “The four Cluster satellites are identical, and so by watching them re-enter the atmosphere in a predictable location with slightly different trajectories and in different weather conditions, we get a unique opportunity to conduct a valuable atmospheric re-entry experiment to study the break-up of satellites.”

The very first of the four Clusters to re-enter on 8 September 2024, Cluster 2 or Salsa, was observed by scientists aboard a plane.

Stijin commented: “The atmospheric re-entry was captured by various onboard instruments, even though the predictions were slightly off. It was a tense period until the sighting could be definitively confirmed.

“To repeat this observational experiment twice more with the lessons learned from Salsa will add an extra dimension to the data, allowing for comparisons and establishing patterns.”

Next steps: Witnessing atmospheric re-entry from the inside

The next goal for ESA’s atmospheric re-entry specialists is to witness a re-entry from the inside and see exactly what happens, how, when, and where, throughout the entire re-entry process with their re-entry mission, Draco.

Draco is scheduled to launch in 2027 and will undergo a fiery re-entry to record exactly what happens to the satellite.

With over 200 sensors, four cameras, and an indestructible capsule to keep the collected data safe, Draco will offer a unique inside perspective of the destructive process.

Stijin concluded: “With the data from the Cluster and Draco re-entries, we will improve re-entry models.

“This helps to better predict where objects will fall and how they affect the atmosphere, and we can build better satellites to further reduce the chance of any pieces reaching the ground and posing risks to people or infrastructure.”