Canada’s collaboration with Europe in subatomic physics is evolving, and TRIUMF plays a key role in international research partnerships through its formal ties with CERN and its contributions to high-energy physics experiments.

In the late 1960s, as a small team of physicists and engineers coalesced in Vancouver, BC, to sketch plans for the world’s largest cyclotron, it was clear they weren’t building their particle accelerator in isolation. TRIUMF, Canada’s particle accelerator centre, founded in 1968 and located on the campus of the University of British Columbia, was conceived as a national laboratory with international aspirations.

Those early aspirations now seem prescient. More than five decades later, TRIUMF stands at the heart of a growing transatlantic research alliance, one that connects Canada not just to its own scientific future but directly to Europe’s most ambitious experiments and institutions. As science increasingly demands borderless thinking, TRIUMF and its European counterparts (particularly CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research) are weaving together their resources, expertise, and ambitions to shape the next chapter in subatomic physics.

A recent signing of a Statement of Intent between Canada and CERN bolsters these decades-long ties and signals a new era of formalised co-operation. But behind the ink on that page is a story years in the making, driven by a shared vision for progress and development in areas like high-energy physics, radiopharmaceutical innovation, and beyond.

Opening a transatlantic channel for discovery

TRIUMF was born in an age of scientific nationalism; the Cold War was pushing nations to stake out sovereign claims in the global research race. But even then, the founding principle of TRIUMF – the collaboration of multiple Canadian universities to build and share a major research facility – hinted at something larger: a willingness to co-ordinate, pool talent, and think beyond institutional boundaries.

Early collaborations with European institutions began modestly. In the 1970s and ’80s, TRIUMF scientists participated in overseas experiments, particularly at CERN, drawn by the scale and scope of European infrastructure. CERN’s high-energy colliders, including the Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS) and later the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), offered Canadian researchers access to energies and detector technologies not available at home.

Conversely, TRIUMF’s expertise in cyclotron technology, particularly in producing intense beams of protons and rare isotopes, began to attract interest from European partners. Its Isotope Separator and Accelerator (ISAC) facilities became world-renowned facilities in rare isotope beam physics, complementing CERN’s ISOLDE facility.

These early entanglements were largely bottom-up: researcher-driven, organically evolving through shared interests. But over time, they have grown deeper, more strategic, and more visionary.

Colliders and code: Canada at CERN

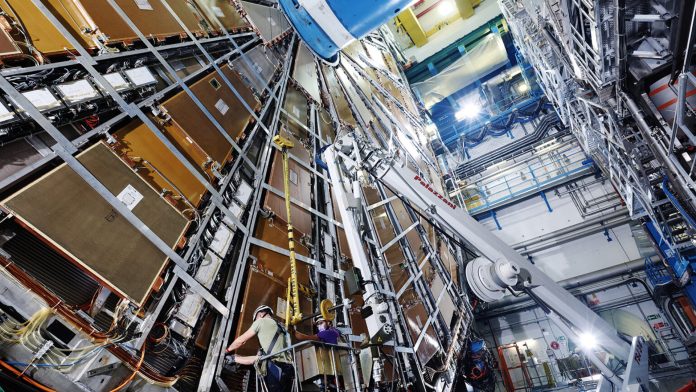

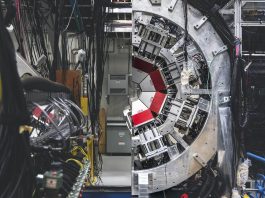

Today, Canadian scientists, many of them based at or affiliated with TRIUMF or its member universities, are deeply embedded in CERN’s flagship high-energy physics programmes. Canada is a full member of the ATLAS collaboration, one of the major experiments at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), and Canadian teams play leading roles in accelerator infrastructure, detector development, and data analysis.

As Canada’s particle accelerator centre, TRIUMF has become the anchor institution for this involvement. Its engineers and physicists have contributed to the ATLAS Muon Spectrometer and Calorimeter systems, advanced data acquisition technologies, and now the High-Luminosity LHC (HL-LHC) upgrade, which will require unprecedented precision and scale in an increasingly harsh radiation environment. Collaboration with CERN isn’t limited to physical detectors; increasingly, it involves the invisible but critical domain of software and computing. The Worldwide LHC Computing Grid, which crunches the vast data streams produced by the LHC, includes Canadian Tier-1 and Tier-2 centres, with TRIUMF serving as the national Tier-1 hub. That means petabytes of data generated in Geneva pass through Vancouver on their way to revealing new physics.

These scientific ties reflect a broader commitment, because Canadian researchers aren’t just participants in European projects; they’re indispensable collaborators shaping them from within.

Building the tools of tomorrow: Accelerator science as a bridge

Accelerator technology is a major pillar of modern experimental physics, and it is an area of research and development naturally suited to international collaboration. Both Canada and Europe are investing heavily in next-generation accelerator science, and here, TRIUMF is both a beneficiary and a contributor. Europe’s future ambitions include projects like the Future Circular Collider (FCC), a proposed 100-km ring collider that would dwarf the LHC, and Canada’s researchers are eyeing opportunities to contribute. But perhaps more immediately, TRIUMF’s own programmes in superconducting radiofrequency (SRF) acceleration – critical for compact, high-power beams – align with European developments at facilities like FAIR (Facility for Antiproton and Ion Research) in Germany and the forthcoming European Spallation Source (ESS) in Sweden.

In return, Canadian expertise in cyclotron development has become a valued resource for European partners. TRIUMF is home to the world’s largest cyclotron, but also operates a suite of smaller, compact cyclotrons used not just in research, but in the production of medical isotopes – a domain where Canadian-European synergy is beginning to accelerate.

Healing across borders: Radiopharmaceuticals and medical isotopes

One of the lesser-known but increasingly vital threads in Canada-Europe collaboration is in the field of nuclear medicine.

TRIUMF has long been a world leader in the production of radiopharmaceuticals – substances that leverage short-lived radioisotopes within a compound that can visualise or even treat a variety of different diseases, including cancer or Alzheimer’s. TRIUMF’s Life Sciences Division built and operationalised Canada’s first functioning Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scanner and has been pioneering innovative techniques for producing a variety of critically needed isotopes for research and clinical trials (including technetium-99m, a workhorse of nuclear imaging) using a cyclotron.

These capabilities are now finding resonance in Europe. European hospitals and research institutions, many of them facing isotope supply challenges, are looking to Canada not only for supply partnerships but also for technical collaboration. Joint research projects between TRIUMF and European partners are exploring new routes for isotope production using cyclotrons rather than nuclear reactors – an approach that’s safer, more scalable, and better suited to decentralised healthcare systems. This isn’t just about logistics; it’s about pushing the boundaries of radiopharmaceutical science. With new GMP-compliant labs coming online as part of its Institute for Advanced Medical Isotopes (IAMI) and its close ties to Canadian biotech startups, TRIUMF will serve as a critical bridge between fundamental science, clinical applications, and scalable solutions for modern healthcare systems.

The statement of intent: Formalising the future

All of this momentum, which comprises decades of shared experiments, co-developed tools, and reciprocal expertise, culminated in a significant diplomatic moment: in April 2025, Canada and CERN signed a Statement of Intent “to strengthen their collaboration in the planning of future projects, including the ongoing Future Circular Collider (FCC) studies, and to expand cooperation on innovative technologies, with a particular focus on the three technology pillars of the field – accelerators, detectors and computing.”

The document, while not a full membership agreement for Canada to join CERN, is a symbolic and practical milestone. It acknowledges TRIUMF’s critical role in Canada’s engagement with CERN and commits both parties to deeper co-operation in key areas, including participation in the HL-LHC and other future colliders, development of next-generation accelerator technologies, joint training and mobility of young scientists and engineers, and shared planning of future large-scale infrastructure.

For TRIUMF, the Statement provides formal recognition of a role it has already been playing for decades: as Canada’s window into Europe’s scientific ambitions. For CERN, it means solidifying access to Canadian brainpower, hardware, and compute capacity.

Importantly, the agreement also carries political and cultural weight. At a time when international collaboration faces geopolitical headwinds, Canada and Europe are doubling down on the idea that science works best when it crosses borders. As global scientific challenges become more complex and expensive, this kind of complementarity is invaluable. No single nation can go it alone in particle physics. By pooling strengths – TRIUMF’s accelerator and isotope innovations, CERN’s collider infrastructure, and their shared knowledge base – Canada and Europe are building a scientific ecosystem stronger than the sum of its parts.

Looking forward: A shared horizon

The story of TRIUMF and CERN is, in a sense, a microcosm of the modern scientific enterprise. What began as a series of informal collaborations among curious researchers has matured into a deliberate partnership supported at the highest levels.

Looking ahead, that partnership is poised to grow. Europe is contemplating its next mega-projects, and Canadian scientists are positioning themselves to contribute from day one. Canada is exploring deeper institutional engagement with CERN, with some pondering the possibility of a formal associate membership. At the same time, TRIUMF is expanding its infrastructure with its Advanced Rare Isotope Laboratory (ARIEL), a new facility and superconducting electron linear accelerator that positions the laboratory as the world’s top producer of high-intensity isotope beams. In this unfolding narrative, TRIUMF is not merely a national lab; it is Canada’s scientific handshake to the world. And increasingly, that handshake is being returned, firmly, from across the Atlantic.

Please note, this article will also appear in the 23rd edition of our quarterly publication.