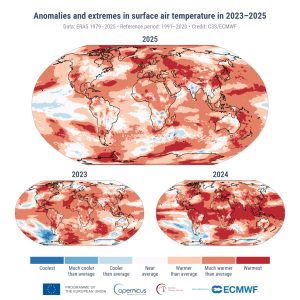

Fresh analysis from leading climate agencies confirms that 2025 was the third-hottest year on record, reinforcing a striking pattern: the past 11 years are now officially the 11 warmest on record.

According to the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S), operated by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), global temperatures in 2025 were just 0.01°C cooler than 2023 and 0.13°C below 2024, which still holds the title of the hottest year on record.

The data release was coordinated with other major climate monitoring bodies, including NASA, NOAA, the UK Met Office, Berkeley Earth and the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO), highlighting broad scientific consensus on the scale and pace of global warming.

Carlo Buontempo, Director of C3S, emphasised the bleak climate picture painted by the analysis: “The fact that the last eleven years were the warmest on record provides further evidence of the unmistakable trend towards a hotter climate.

“The world is rapidly approaching the long-term temperature limit set by the Paris agreement. We are bound to pass it; the choice we now have is how to manage best the inevitable overshoot and its consequences on societies and natural systems.”

Crossing a critical climate milestone

One of the most significant findings is not tied to a single hottest year, but to a troubling longer-term trend. The three-year period from 2023 to 2025 averaged more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels (1850–1900).

This marks the first time any three-year span has exceeded the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C limit, a benchmark intended for long-term global warming rather than short-term fluctuations.

Based on multiple analytical methods, scientists now estimate that long-term global warming has reached around 1.4°C, putting the 1.5°C threshold within reach before the end of this decade – more than ten years earlier than anticipated when the agreement was signed.

How warm was 2025, exactly?

Using the ERA5 reanalysis dataset, Copernicus reports that global surface air temperatures in 2025 were 1.47°C above pre-industrial levels, following 1.60°C in 2024, the hottest year to date.

While slightly cooler than the previous two years, 2025 still delivered exceptional warmth across large parts of the planet.

Air temperatures over global land areas ranked as the second warmest on record, and the polar regions once again stood out for their extremes.

Polar extremes offset cooler tropics

In contrast to 2023 and 2024, temperatures across the tropics were somewhat lower in 2025, though still well above average in many regions.

Scientists attribute this partly to ENSO-neutral or weak La Niña conditions in the equatorial Pacific, which tend to suppress global temperatures relative to El Niño years.

That cooling influence was offset by dramatic warming at the poles. Antarctica recorded its warmest annual temperatures ever, while the Arctic experienced its second warmest year on record.

Elevated temperatures were also observed in parts of the northeastern Atlantic, the Pacific, Europe and central Asia.

Why the last three years were so hot

Researchers point to two dominant drivers behind the exceptional warmth of 2023–2025. The first is the continued accumulation of greenhouse gases, driven by human emissions and a reduced ability of natural systems to absorb carbon dioxide.

The second is the role of the oceans. Sea-surface temperatures reached unusually high levels worldwide, boosted by El Niño conditions earlier in the period and amplified by long-term climate change.

Additional influences include shifts in aerosols, low cloud cover and atmospheric circulation patterns.

Heat stress, wildfires and human health

In 2025, around half of the world’s land area experienced more days than average with strong heat stress, defined as a “feels-like” temperature of 32°C or higher.

The World Health Organization (WHO) identifies heat stress as the leading cause of weather-related deaths globally.

Hot, dry and windy conditions also fuelled severe wildfires, particularly in parts of Europe and North America.

According to Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS) data, Europe recorded its highest annual wildfire emissions, with smoke and pollutants degrading air quality over large regions.

Extreme events add urgency to the data

Although the report does not directly attribute individual disasters to climate change, 2025 was marked by record heatwaves, powerful storms and major wildfires across Europe, Asia and North America, including events in Spain, Canada and Southern California.

These extremes provide real-world context for the statistics and help explain why public and political attention on which year will be the next hottest year continues to intensify.

Monitoring the path ahead

Scientists stress that rising greenhouse gas concentrations – largely the result of human activity – remain the primary cause of long-term warming.

Laurence Rouil, Director of Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service at ECMWF, explained: “Atmospheric data from 2025 paints a clear picture: human activity remains the dominant driver of the exceptional temperatures we are observing. Atmospheric greenhouse gases have steadily increased over the last 10 years.

“We will continue to track greenhouse gases, aerosols, and other atmospheric indicators to help decision makers understand the risks of continuing emissions and respond effectively, reinforcing synergies between air quality and climate policies. The atmosphere is sending us a message, and we must listen.”

As competition for the title of hottest year continues, the bigger message from the data is clear: record-breaking warmth is no longer an exception – it is becoming the norm.