The rapid growth of electric vehicles (EVs) has sparked both excitement and concern.

While EVs are reducing emissions from transport, they also bring a looming challenge: what to do with the massive number of batteries once they reach the end of their life.

Many of today’s lithium-ion batteries end up in landfills, creating toxic waste and wasting valuable resources.

But a team of researchers at MIT may have found a game-changing solution that could transform EV battery recycling.

Rethinking battery design from the ground up

Traditionally, the battery industry has focused on maximising performance first, then tackling recycling challenges later.

This has led to batteries made with complex structures and hazardous materials that are extremely difficult to break down.

The MIT team took the opposite approach. Instead of designing high-performing batteries first, they started with the question: What if we could make a battery from the beginning that was built for easy recycling?

Their answer lies in a new type of self-assembling material that functions as the electrolyte – the part of a battery that carries lithium ions between electrodes.

Unlike conventional electrolytes, which are flammable and decompose into toxic byproducts, this new material can quickly dissolve in a simple organic liquid.

Once dissolved, the entire battery essentially falls apart, allowing its components to be separated and recycled with ease.

How the self-assembling material works

The new electrolyte material is made from molecules called aramid amphiphiles (AAs), which are chemically similar to Kevlar.

These molecules self-assemble into strong, nanoribbon structures that remain stable while conducting lithium ions.

To improve conductivity, the researchers added polyethene glycol (PEG) to the molecules, creating pathways for ions to move through the battery.

When pressed together, the nanoribbons form a tough, solid electrolyte capable of withstanding the stresses of regular battery use. But the magic happens when the battery reaches the end of its life.

Once submerged in organic solvents, the nanoribbons disassemble within minutes, and the electrolyte dissolves completely.

This triggers the entire battery to break apart – like cotton candy dissolving in water – leaving its cathode and anode materials ready for direct recycling.

Testing the technology in real batteries

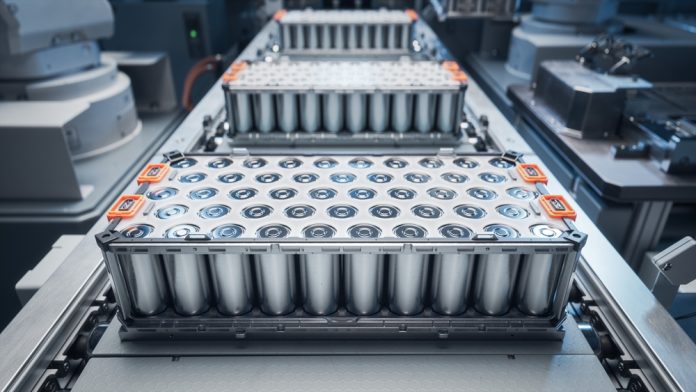

To prove the concept, the team built a solid-state battery using common electrode materials: lithium iron phosphate as the cathode and lithium titanium oxide as the anode.

The nanoribbon electrolyte successfully moved lithium ions between the electrodes, though its performance fell short of today’s best commercial batteries.

The researchers attribute this limitation to a bottleneck in how quickly lithium ions can move between the nanoribbons and the electrodes.

However, they stress that this experiment was meant to demonstrate recyclability rather than create a top-performing battery.

In future designs, the material could be used as just one layer of a battery’s electrolyte system, enabling recyclability without compromising performance.

A new vision for EV battery recycling

The MIT breakthrough represents a proof of concept for designing batteries with recyclability as a core principle rather than an afterthought. While more work is needed to optimise the material, the potential implications are significant.

If adopted at scale, this approach could help recover large amounts of lithium and other critical minerals from used batteries, reducing dependence on mining and lowering costs.

In fact, reusing materials through EV battery recycling could have the same economic effect as opening new lithium mines in the United States.

This technology could also help secure domestic supplies of critical minerals. As demand for EVs skyrockets, ensuring a stable and sustainable lithium supply is crucial.

Recycling existing batteries could play a major role in avoiding price spikes and supply shortages in the future.

What comes next

The researchers acknowledge that commercial adoption won’t happen overnight. Battery manufacturers are often reluctant to change established designs, especially when new materials might affect performance.

However, as new battery chemistries are developed over the next five to ten years, the opportunity to integrate recyclable components from the start will grow.

The team is now exploring ways to optimise the electrolyte’s performance, improve ion transfer, and test compatibility with a wider range of battery types.

With support from the U.S. Department of Energy and the National Science Foundation, their work could pave the way for a more circular EV economy.

Toward a sustainable battery future

As EV adoption accelerates worldwide, the question of what happens to millions of used batteries becomes increasingly urgent.

MIT’s self-disassembling electrolyte offers a radical new approach: designing batteries that can take themselves apart when it’s time to recycle.

While the material is still in early stages, it represents a bold step toward solving one of the biggest sustainability challenges of the EV era.

By reimagining how batteries are built, this breakthrough could help turn tomorrow’s mountain of waste into a renewable source of critical resources, making EV battery recycling both practical and scalable.