A groundbreaking energy project at CERN is proving that cutting-edge science and everyday sustainability can go hand in hand.

A newly operational heat exchange system is now capturing waste heat from the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) and redirecting it to warm homes and businesses in the nearby French town of Ferney-Voltaire.

What was once excess heat released into the atmosphere is now a low-carbon resource supporting a growing local heating network.

The Large Hadron Collider explained

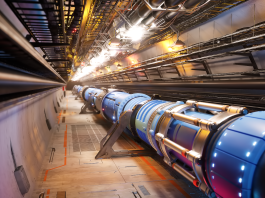

The Large Hadron Collider is the world’s most powerful particle accelerator, located underground near Geneva on the French–Swiss border.

It propels subatomic particles to near-light speeds before smashing them together, allowing scientists to study the fundamental building blocks of the Universe.

The LHC has been instrumental in major discoveries, including the Higgs boson, and plays a central role in advancing our understanding of physics.

Its vast scale and energy demands also make it uniquely suited to innovative energy recovery projects such as this heat exchange system.

Turning scientific waste heat into community energy

Since mid-January, thermal energy recovered from the LHC’s cooling infrastructure has been feeding into a district heating network serving a new residential and commercial development in Ferney-Voltaire.

Officially inaugurated in December, the network is expected to provide heating equivalent to several thousand homes. By relying on recovered heat instead of gas or other fossil fuels, the project is set to prevent the release of thousands of tonnes of carbon dioxide each year.

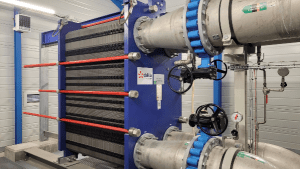

At the heart of the initiative is an advanced heat exchange system that captures hot water produced during the cooling of sensitive accelerator equipment.

Rather than discarding this heat through cooling towers, CERN now transfers it directly into the town’s heating infrastructure, transforming a by-product of research into a valuable energy source.

How the heat exchange system works

The Large Hadron Collider stretches across 27 kilometres and includes eight major surface points.

One of these, known as Point 8, sits close to Ferney-Voltaire and houses water-cooled installations, including cryogenic systems. As cooling water circulates through this equipment, it absorbs heat and exits at high temperatures.

In the new configuration, this hot water flows through two industrial-scale heat exchangers, each rated at 5 MW. These exchangers transfer thermal energy to the municipal heating network without interfering with CERN’s scientific operations.

Currently, the town draws up to 5 MW of heat, but the system has the potential to double that output during periods of full accelerator activity.

Energy supply during maintenance periods

Even when the LHC pauses operations, the heat exchange system remains valuable. From summer 2026, CERN will enter Long Shutdown 3, a multi-year maintenance and upgrade phase preparing for the High-Luminosity LHC.

During this time, some Point 8 facilities will continue to require cooling, allowing between 1 and 5 MW of heat to be supplied to the network for most of the shutdown, apart from a limited five-month interruption.

This continuity ensures that the heating network remains resilient while maintaining flexibility around CERN’s core research mission.

Part of a broader sustainability strategy

The Ferney-Voltaire project is just one element of CERN’s wider commitment to responsible energy management.

Energy recovery sits alongside efficiency improvements and consumption reduction within its ISO 50001-certified strategy.

Other initiatives include heat recovery at the Prévessin Data Centre, scheduled to supply most on-site buildings from winter 2026/2027, and future plans to reuse heat from cooling towers at LHC Point 1.

Together, these projects are expected to save between 25 and 30 gigawatt-hours of energy annually by 2027, demonstrating how a well-designed heat exchange system can bridge the gap between world-class science and real-world climate action.