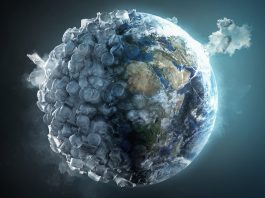

Northwestern University chemists have introduced a new plastic upcycling process that can drastically reduce, or even fully bypass, the laborious chore of pre-sorting mixed plastic waste.

The plastic upcycling process utilises a new, inexpensive nickel-based catalyst that selectively breaks down polyolefin plastics, consisting of polyethylenes and polypropylenes.

These single-use plastics dominate nearly two-thirds of global plastic consumption. This means industrial users could apply the catalyst to large volumes of unsorted polyolefin waste.

How the method breaks down plastic waste into liquids

When the catalyst breaks down polyolefins, the low-value solid plastics are transformed into liquid oils and waxes, which can be upcycled into higher-value products, including lubricants, fuels, and candles.

Not only can it be used multiple times, but the new catalyst can also break down plastics contaminated with polyvinyl chloride (PVC), a toxic polymer that notoriously makes plastics “unrecyclable.”

“One of the biggest hurdles in plastic recycling has always been the necessity of meticulously sorting plastic waste by type,” said Northwestern’s Tobin Marks, the study’s senior author.

“Our new catalyst could bypass this costly and labour-intensive step for common polyolefin plastics, making recycling more efficient, practical and economically viable than current strategies.”

The polyolefin predicament

From yoghurt cups and snack wrappers to shampoo bottles and medical masks, most people interact with polyolefin plastics multiple times throughout the day.

Due to its versatility, polyolefins are the most widely used plastic in the world. According to some estimates, the industry produces over 220 million tons of polyolefin products globally each year.

However, according to a 2023 report in the journal Nature, recycling rates for polyolefin plastics are alarmingly low, ranging from less than 1% to 10% worldwide.

The main reason for this disappointing recycling rate is the polyolefin’s sturdy and stubborn composition. It contains small molecules linked together with carbon-carbon bonds, which are famously difficult to break.

Issues with current plastic upcycling processes

Currently, only a few, less-than-ideal plastic upcycling processes exist for recycling polyolefins. It can be shredded into flakes, which are then melted and downcycled to form low-quality plastic pellets.

However, because different types of plastics have varying properties and melting points, the process requires workers to separate them with meticulous care. Even small amounts of other plastics, food residue or non-plastic materials can compromise an entire batch.

Another option involves heating plastics to incredibly high temperatures, reaching 400 to 700°C. Although this process degrades polyolefin plastics into a useful mixture of gases and liquids, it’s extremely energy intensive.

Breaking down plastics into useful hydrocarbons

To uncover an energy efficient solution, the team looked to hydrogenolysis, a process that uses hydrogen gas and a catalyst to break down polyolefin plastics into smaller, useful hydrocarbons.

While hydrogenolysis approaches already exist, they typically require extremely high temperatures and expensive catalysts made from noble metals, such as platinum and palladium.

For its polyolefin plastic recycling catalyst, the Northwestern team pinpointed cationic nickel, which is synthesised from an abundant, inexpensive and commercially available nickel compound.

“Compared to other nickel-based catalysts, our process uses a single-site catalyst that operates at a temperature 100°C lower and at half the hydrogen gas pressure,” Kratish said.

“We also use ten times less catalyst loading, and our activity is ten times greater. So, we are winning across all categories.”

Adding PVC to the recycling process

The catalyst is so thermally and chemically stable that it maintains control even when exposed to contaminants like PVC.

Used in pipes, flooring, and medical devices, PVC is visually similar to other types of plastics but significantly less stable upon heating. Upon decomposition, PVC releases hydrogen chloride gas, a highly corrosive byproduct that typically deactivates catalysts and disrupts the recycling process.

Amazingly, not only did Northwestern’s catalyst withstand PVC contamination, but PVC accelerated its activity. Even when the total weight of the waste mixture consists of 25% PVC, the scientists found that their catalyst still worked with improved performance.

This unexpected result suggests the team’s method might overcome one of the biggest hurdles in mixed plastic recycling – breaking down waste currently deemed “unrecyclable” due to PVC contamination.