Space telescopes are outgrowing the limits of Earth-based launches. In-space assembly (ISA) is a scalable, technically viable way to build next-generation observatories and orbital equipment.

Bigger extraterrestrial telescopes promise groundbreaking discoveries, but building these machines on Earth has hit a wall. Rockets can only carry so much, and complex folding systems like those of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) push engineering to its limits.

Jack Shaw, writer and editor at Modded, explores the innovation of in-space assembly (ISA) for deploying large space infrastructure and craft into orbit.

The limits of Earth-based assembly

Earth’s atmosphere and logistical limitations have kept most telescopes small so they fit into launch vehicles or the rocket’s fairings and survive the intense vibrations of launch. The JWST is currently the largest space observatory with a 6.5-metre mirror, and it barely fits inside the Ariane 5 rocket.

The fit was only possible because it was designed to fold and consists of 18 mirror segments. The segments increased the risk and cost — $10.8 billion for total design, build, and operations. Next-generation observatories will need mirrors exceeding 15 metres, which makes a fold-up design untenable.

Why bigger space telescopes are necessary

Larger observatories and space telescopes have bigger apertures, which let them capture more distant objects with higher resolution. Larger mirrors reduce noise and provide flexible observation across the visible, infrared, and ultraviolet spectrums. So, the bigger the mirror, the better the data, but launching and assembling these gigantic orbital viewers will require overcoming some challenges.

Launch constraints

When companies design any spacecraft, they must address logistical and structural limitations. Here are some of the biggest ones:

- Fairing diameter and volume: Standard launch vehicles can accommodate payloads roughly 4-6.5 metres in diameter, though the newer Space Launch System rockets can accommodate much larger payloads with larger fairings. Anything bigger than this requires folding or splitting it into smaller components. Limited load capacity means fitting a large viewing vehicle into a single rocket isn’t possible.

- Mass limits: Larger telescopes require advanced lightweight materials like beryllium or ultra-low expansion glass, but the total payload is still likely several tonnes. If this exceeds the rocket’s thrust capacity, it won’t break free from the Earth’s atmosphere.

- Deployment risks: Complex hinges, actuators, and unfolding mechanisms introduce hundreds of potential points of failure.

Benefits of in-space assembly

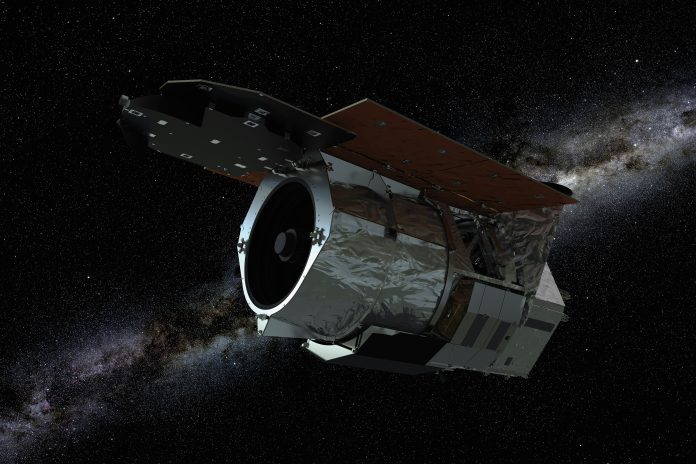

In-space assembly (ISA) involves launching modular components into low Earth orbit or a staging point like Sun-Earth (L2). The components may take several trips to reach the staging area, but this allows for assembling larger observatories. There, robotic systems put the pieces together. It may be possible to use this technology to create 25-metre aperture space telescopes that exceed single-launch designs.

ISA designs require fewer moving parts than folding systems like the JWST. A lost module doesn’t compromise the mission — components can be rebuilt or re-launched. With modular ISA, the size of the final design no longer relies on the total fairing room on the rocket. It also enables serviceable designs, which can be upgraded, refuelled, or repaired in orbit.

Assembly considerations for ISA

Designing a telescope that uses ISA involves a mind shift. Scientists place modular structures like mirror segments, structural trusses, and sunshields independently into orbit, similar to assembling LEGO blocks into a larger structure. Remote assembly with precision robotics enables the positioning of components with sub-millimetre tolerances.

In space, screws, bolts and other fasteners withstand incredible forces, which increase tension and can lead to failure. Typically, a fastener is lubricated while tightened to reduce the friction and torsion. In orbit, regular lubricants won’t work, so the fasteners for orbital applications are instead coated with various alloys that prevent friction and degradation.

Step-by-step assembly of a space observatory in orbit

NASA’s concept mission includes constructing a telescope in space as opposed to launching a fully assembled one using the following steps:

- Launch of the core spacecraft bus: The first launch will carry the bus containing electronics, fuel, power systems, and robotic arms or a Space Infrastructure Dexterous Robot (SPIDER). The SPIDER enables remote assembly and also carries additional components for repairs.

- Module delivery: Follow-on launches deliver mirror modules, backplane trusses, sunshield elements, and instruments. These components fit within the limited room in the rocket fairings.

- Robotic capture and integration: The robotic arms use AI-guided vision systems to attach each module to the growing structure, starting with the primary mirror struts.

- Primary mirror alignment: Once the 18 mirror modules with 19 hexagonal mirror segments each are positioned and aligned, the high-resolution wavefront sensing systems ensure optical accuracy.

- Sunshield and secondary mirror deployment: Deployable booms extend a sunshield and secondary mirror to the proper focal distance.

- Instrument installation and final checks: The SPIDER slots scientific instruments into dedicated bays. It connects power, data, and thermal interfaces. The entire observatory undergoes system validation.

- Orbital transfer and commissioning: The completed telescope shifts to its final orbit location – usually L2 – for operational testing and science commissioning.

Strategic benefits for investors

ISA creates a scalable model for building orbital infrastructure, including telescopes, spacecraft, and satellites. This is a potential investment opportunity for sustainability-focused aerospace leaders and investors.

By lowering the cost per capability, ISA reduces budget spikes and enables mission phasing. Expand the lifespan of existing spacecraft and orbital structures with in-orbit servicing, aligning with circular economic principles.

Commercial participation from entities like SpaceX and Blue Origin can open possibilities for robotic manufacturers to engage in modular construction. Scalable platforms constructed with ISA pave the way for megastructures, orbital solar farms that can potentially provide energy during the night, and Earth imaging constellations.

Risks and redundancies of ISA

ISA isn’t without challenges. Assembly in orbit carries risks like robotic malfunctions, misalignment in microgravity, mismatching thermal expansion profiles, and launch delays disrupting the modular timeline.

Ways to address the risks include manufacturing redundant modules in advance, designing robotic systems that can self-calibrate, and breaking down assembly sequences into smaller, independently verifiable tasks. Autonomous fault detection and reconfiguration protocols protect mission continuity.

FAQs

What is in-space assembly, and why is it important for future space telescopes?

ISA is building or expanding spacecraft like telescopes directly in orbit using modular parts and robotic systems. It allows for much larger and more complex observatories than could be launched in one piece, overcoming size and weight limits imposed by rockets.

Is in-space assembly too risky to be practical?

ISA involves new risks, but it may reduce others. By assembling structures in stages, issues are detected earlier and fixed, avoiding catastrophic failures. Reusable launch systems and robotic technologies are rapidly evolving, making ISA more cost-effective than a decade ago.

Will ISA make space telescopes easier to repair or upgrade?

Modular construction means individual parts, like instruments or power systems, could be swapped or upgraded without replacing the entire observatory. This opened the door for long-term servicing missions like Hubble, which benefited from astronaut repairs.

The future of space telescope assembly

The design of orbital viewing platforms needs to bridge Earth’s launch constraints. In-space assembly isn’t just a workaround – it’s the gateway to next-generation scientific and commercial observation infrastructure. Precision robotics, modular architecture, and advanced materials make ISA the most promising prospect.

This engineering innovation appeals to sustainably-minded business leaders and is a strategic investment in infrastructure for tomorrow’s space economy.