The LISA experiment is a space-borne gravitational wave detector aiming to measure waves from massive celestial events, enhancing our understanding of the universe by capturing signals that ground-based observatories like LIGO and Virgo cannot detect.

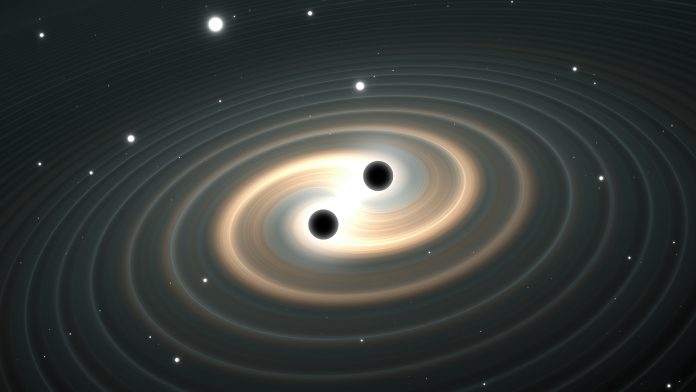

Gravitational waves have emerged as one of the most exciting frontiers in modern astrophysics, reshaping our understanding of the universe and the fundamental forces at play. These ripples in the fabric of space-time, first predicted by Albert Einstein over a century ago, carry with them invaluable information about some of the most cataclysmic events in our cosmos, such as the merging of black holes and neutron stars.

The Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) and its European counterpart, Virgo, marked a historic milestone in 2015 when they successfully detected gravitational waves for the first time. These ground-based facilities have provided profound insights into the nature of black holes, stellar evolution, and the dynamics of the universe, astronomical events that were previously invisible.

Despite their groundbreaking achievements, LIGO and Virgo operate at a limited frequency range, primarily focusing on events involving smaller black holes. This is where the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) comes into play.

The Innovation Platform spoke with Mr Oliver Jennrich, Head of the Astrophysics Section at the European Space Agency, and Mr Filippo Marliani, LISA’s Project Manager, to delve into the intricacies of the LISA mission, its objectives, and the transformative potential it holds for our understanding of the universe.

Can you explain the LISA experiment and its primary objectives?

LISA is a space-borne gravitational wave detector. It will measure gravitational waves in a frequency range between 0.1 mHz and 1Hz by registering the changes in the phase of laser light transmitted between three satellites, 2.5 million km apart. The main sources of gravitational waves in this frequency range are :

- Merging massive black holes like those frequently found in the centre of galaxies,

- Compact binary systems in the Milky Way, i.e. double star systems where both stars are small, compact objects like white dwarfs, neutron stars or small black holes

- Small compact objects (neutron stars, black holes) falling into the massive black holes in the center of galaxies.

Can you discuss the nature of gravitational waves, how they are generated, and their importance for our understanding of the universe?

Gravitational waves are ‘ripples in space-time’, small disturbances in space-time that propagate with the speed of light and that are generated whenever objects are accelerated. Because gravitational waves are very weak, it requires huge masses (at least a few times the mass of the Sun) to generate gravitational waves that can be detected with our current technology. Not unlike light (or electromagnetic radiation in general), they are transversal waves and have two polarisations. In contrast to electromagnetic radiation, they are not acting on electric charge, but mass and they are not dipole waves, but quadrupole waves, leading to a ‘squash and squeeze’ deformation of an ensemble of masses.

Gravitational waves are excellent tools to observe the universe because they essentially suffer from no absorption by dust, allowing us a very clear view of the sources even at very large distances, all the way to the time when the first galaxies formed.

They also provide an alternative view of objects that we also observe in the electromagnetic spectrum, potentially allowing us to get a better handle on the history of the universe, how the large structures we observe today formed and on the way the universe expands.

How will the LISA experiment enhance our current understanding of gravitational waves compared to ground-based observatories like LIGO and Virgo?

LISA targets a different frequency range from ground-based detectors. As the wavelength of the signals is proportional to the mass of the sources, this LISA’s sources are generally more masive than LIGO’s. Where LIGO targets objects from a few to about 100 solar masses, LISA will observe objects up to masses of a million solar masses. This allows us to address different questions about the universe and to ‘look’ further back in time.

There is a small overlap between the sources for LISA and the ground-based detectors. At the high-frequency end of LISA’s sensitivity (~1 Hz), we can observe binary systems that, over the course of the next weeks and months, will enter the LIGO/Virgo sensitivity band. For those sources, LISA can serve as a ‘pre-warning’ system for ground-based detectors, allowing for a much more targeted search in their data stream.

What challenges does the LISA mission face in terms of technology and implementation?

In a much simplified and very high-level way, there are two main challenges: detecting the very small changes in the laser phases (~10^-5 of a wavelength or 10s of picometer) and making sure that those changes are caused by gravitational waves and not by instrumental noise.

The former requires laser light to be exchanged between the satellites, with enough of the light received by the respective other satellite (the laser beam widens up to many kilometres in diameter over the distance of 2.5 million km) and to determine the phase of the incoming laser to a local reference. This measurement principle (interferometry) is well established on the ground in, e.g., LIGO and Virgo, but the distances, aiming at the other satellite (and hitting it), and the relatively small amount (a few 100 pW) of laser light received makes this a challenging task.

The latter challenge has at its core the ability to decouple the position of the spacecraft from external forces as much as possible so that the position is only determined by gravity and as little as possible influenced by, e.g., solar radiation pressure, interplanetary magnetic fields, residual particles, etc. For that purpose, each satellite has two free-falling test masses that form the reference for the position measurement. This technology has been demonstrated by the LISA Pathfinder mission from 2015-2017, showing that we can keep the influences of non-gravitational forces onto the test masses to the necessary minimum.

Somewhat uniquely, LISA’s satellites are an intrinsic part of the measurement chain. The distribution of the masses (and the change of this distribution) must be known to a high precision to be able to compensate for the pull of the spacecraft on the test masses.

Can you detail the European Space Agency’s role in the development of the LISA experiment?

ESA is the lead agency in the mission, providing the spacecraft, the launcher and the general mission architecture. Significant parts of the instruments and the data analysis effort are provided by ESA member states, and NASA, as the international partner, provides the telescopes, the lasers, and the system that controls the electric charge of the test masses. NASA also contributes to the data analysis effort.

What is the timeline for the ESA’s LISA mission, and what are the key milestones we should be looking for before the launch in the mid-2030s?

The industrial activities commenced in January 2025. The first two years will focus on the consolidation of the spacecraft design, which culminates with the System Preliminary Design review planned in Q4 2026, and the build-up of the industrial consortium, involving more than 50 European industries. Key project milestones are the thermal and mechanical tests planned from mid-2028 to the beginning of 2029. In the last quarter of 2030, the Critical Design Review will confirm the goodness of the system design, including the testing activities performed on the early development models.

At the beginning of 2031, the first flight hardware of the payload will be delivered to the Prime contractor, thus initiating the integration of the first spacecraft, which will conclude at the end of the same year. The environmental campaign of the first spacecraft will occupy the first months of 2032, while the second and third spacecraft will be assembled and tested in a staggered fashion in 2032, 2033 and 2034. The Flight Acceptance Review is currently planned for 2034 for a launch in summer 2035, considering adequate margins.

In what ways do you think LISA could impact future scientific research and collaboration on a global scale? What are some expected scientific discoveries or breakthroughs that could come from the successful operation of LISA?

As far as large space science missions go, the international collaboration and the size and composition of the scientific community are not unusual. Globally, NASA partners with ESA on a lot of missions (and vice versa), so LISA is not too unusual either. So LISA will be confirming what global collaboration and teamwork can achieve – a unique mission with unprecedented scale and sensitivity.

The most exciting scientific discoveries are the unexpected ones. We expect to identify thousands of galactic binary systems in our galaxy, many of them obscured in the electromagnetic spectrum. We will, for the first time ‘see’ mergers of objects a million times more massive than our Sun; we will be able to compare the signals of those mergers to the calculations of General Relativity and thus test Einstein’s famous theory once more. We will be able to probe the physics at the very centre of galaxies by observing the demise of small objects falling into the central black hole. And we might even be able to detect the echoes of the Big Bang.

Please note, this article will also appear in the 22nd edition of our quarterly publication.