The ESA-led Solar Orbiter mission has successfully identified various outbursts from the Sun, splitting the flood of energetic particles into two distinct groups.

The Sun is the most energetic particle accelerator in the Solar System. It whips up electrons to nearly the speed of light and flings them out into space, flooding the solar system with so-called ‘Solar Energetic Electrons’ (SEEs).

Researchers used Solar Orbiter to pinpoint the source of these energetic electrons and trace what is observed in space back to what’s happening on the Sun.

They identified two types of SEE, each with a distinct story: one associated with intense solar flares and the other with larger eruptions of hot gas from the sun’s atmosphere, known as coronal mass ejections (CMEs).

Solar Orbiter forms a clearer understanding of events on the Sun

While scientists were aware that two types of SEE events existed, Solar Orbiter was able to measure many events and look far closer to the Sun than other missions had, to reveal how they form and leave its surface.

Alexander Warmuth from the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam explained: “We were only able to identify and understand these two groups by observing hundreds of events at different distances from the sun with multiple instruments – something that only Solar Orbiter can do.

“By going so close to our star, we could measure the particles in a ‘pristine’ early state and therefore accurately determine the time and place they started at the Sun.”

Why do the electrons ‘lag’ in space?

The researchers used the Solar Orbiter to detect SEE events at different distances from the Sun. This allowed them to study how electrons behave as they travel through the Solar System, answering a lingering question about these energetic particles.

When we see a solar flare or CME, there can often be a ‘lag’ between what happens on the Sun’s surface and the release of energetic electrons into space. In extreme cases, the particles can take hours to escape, but why?

“It turns out that this is at least partly related to how the electrons travel through space – it could be a lag in release, but also a lag in detection,” said ESA Research Fellow Laura Rodríguez-García.

“The electrons encounter turbulence, get scattered in different directions, and so on, so we don’t spot them immediately.”

The study fulfils an important goal of the Solar Orbiter: to continuously monitor our star and its surroundings, tracing ejected particles back to their sources at the Sun.

Daniel Müller, ESA Project Scientist for Solar Orbiter, commented: “During its first five years in space, Solar Orbiter has observed a wealth of Solar Energetic Electron events. As a result, we’ve been able to perform detailed analyses and assemble a unique database for the worldwide community to explore.”

Solar Orbiter’s role in space weather forecasting

Crucially, Space Orbiter’s findings are important for our understanding of space weather, where accurate forecasting is essential to keep our spacecraft operational and safe.

One of the two types of SEE events is more significant for space weather: the one associated with CMEs, which tend to contain more high-energy particles and therefore pose a greater threat of damage.

Because of this, being able to distinguish between the two types of energetic electrons is hugely relevant for our forecasting.

Müller said: “Knowledge such as this from Solar Orbiter will help protect other spacecraft in the future, by letting us better understand the energetic particles from the Sun that threaten our astronauts and satellites.”

The future of detecting hazardous solar events

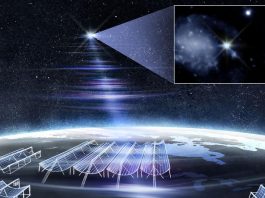

Following on from Solar Orbiter, ESA’s Vigil mission will pioneer a revolutionary approach, operationally observing the ‘side’ of the Sun for the first time, unlocking continuous insights into solar activity.

Launching in 2031, Vigil will detect potentially hazardous solar events before they come into view from Earth, providing us with advance knowledge of their speed, direction, and chance of impact.

Our understanding of how Earth responds to solar storms will also be further investigated with the launch of ESA’s SMILE mission next year. SMILE will study how Earth endures the relentless ‘wind’, and sporadic bursts of fierce particles thrown our way from the Sun, exploring how the particles interact with our planet’s protective magnetic field.