Researchers at Tohoku University have developed a plasma propulsion system that could revolutionise space debris removal and make Earth’s orbit safer.

Earth’s orbit is becoming increasingly crowded. Thousands of defunct satellites, discarded rocket stages, and fragments from past collisions now circle the planet at speeds faster than bullets.

This expanding cloud of debris poses a mounting danger to active satellites and future crewed missions.

Even a piece of debris just a few centimetres wide could cause catastrophic damage to a functioning spacecraft, given the extreme velocities involved.

With the number of satellites expected to grow significantly in the next decade, scientists are racing to find safe and efficient ways to clear this orbital clutter before it spirals into an even bigger problem.

Understanding the dangers of space debris

To appreciate why such innovations are urgently needed, it’s important to understand the threat of space debris.

The debris population includes everything from old satellite parts to tiny shards created by collisions and explosions. Even fragments as small as a paint chip can pierce spacecraft walls at orbital speeds.

The danger is not just theoretical. Past incidents, such as the 2009 collision between an active US satellite and a defunct Russian one, created thousands of new fragments that remain in orbit today.

Each collision increases the risk of a chain reaction, sometimes referred to as the Kessler Syndrome, where debris collisions generate more debris, potentially rendering parts of orbit unusable.

Plasma propulsion: A new approach

At the forefront of efforts to combat space debris is plasma propulsion, a technology that uses superheated, electrically charged gas to generate thrust.

Traditionally, space debris removal has relied on direct-contact solutions – nets, harpoons, or robotic arms. While innovative, these methods carry the risk of entanglement due to the unpredictable tumbling of debris.

Plasma propulsion offers a non-contact alternative. By firing streams of plasma at debris, the idea is to gradually slow it down until Earth’s gravity pulls it back into the atmosphere, where it burns up harmlessly.

The challenge has been ensuring that the removal satellite itself remains stable while performing this manoeuvre.

A Japanese breakthrough

Kazunori Takahashi, associate professor at Tohoku University’s Graduate School of Engineering, has taken a major step toward solving this problem.

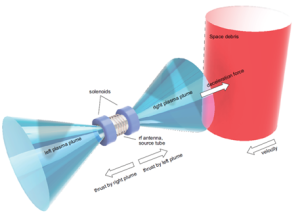

His research details the development of a bidirectional plasma ejection type electrodeless plasma thruster.

Unlike traditional thrusters that fire plasma in only one direction, Takahashi’s design ejects plasma streams both forward and backwards.

This dual ejection balances out the forces, preventing the removal satellite from being pushed off course while still slowing down the targeted debris.

To further boost efficiency, Takahashi integrated a magnetic field structure called a cusp, which keeps the plasma flow tightly contained and directed.

Laboratory vacuum tests showed that this configuration not only stabilised the plasma propulsion system but also tripled the deceleration force compared to previous designs.

Why argon matters

Another key advantage of Takahashi’s plasma propulsion system is its fuel source.

Unlike conventional thrusters that often rely on expensive propellants like xenon, this new system can operate on argon, a far cheaper and more abundant option.

This makes large-scale debris cleanup missions more feasible and cost-effective, removing one of the biggest barriers to implementation.

From lab to orbit

So far, these tests have taken place in controlled laboratory environments. The next challenge will be to demonstrate the thruster’s performance in real-world space conditions.

If successful, satellites equipped with bidirectional plasma propulsion could lock onto space junk and deorbit it in roughly 100 days – a game-changing timeline in the battle against orbital debris.

Takahashi’s plasma propulsion system represents more than just a laboratory achievement. It offers a realistic pathway to addressing one of the most pressing challenges in modern spaceflight: maintaining a safe and sustainable Earth orbit.

As satellite constellations for communication, navigation, and climate monitoring continue to expand, the ability to remove dangerous debris efficiently and safely will be essential. Plasma propulsion could be the key technology that turns the tide in humanity’s fight against orbital junk.