Europe is heating up faster than any other continent, and the costs of that warming are no longer theoretical.

Floods, droughts, heatwaves and wildfires are already draining tens of billions of euros from the European economy every year.

A new briefing from the European Environment Agency (EEA) makes a stark case that accelerating investment in climate adaptation across agriculture, energy and transport is no longer optional but essential for protecting Europe’s prosperity and competitiveness.

What climate adaptation means in practice

Climate adaptation refers to adjusting systems, infrastructure and practices to reduce vulnerability to the impacts of climate change and to cope with unavoidable consequences.

Unlike mitigation, which focuses on cutting greenhouse gas emissions, climate adaptation accepts that some degree of climate change is already here and aims to limit its damage.

In agriculture, adaptation can involve shifting to more drought-resistant crops, improving soil health to retain moisture, or modernising irrigation systems to use water more efficiently.

In the energy sector, it includes reinforcing power grids against heat and storms, diversifying renewable energy sources, and protecting coastal energy infrastructure from rising sea levels.

For transport, climate adaptation may mean redesigning roads and railways to withstand higher temperatures, elevating infrastructure in flood-prone areas, or strengthening ports against storm surges.

These measures are not just defensive. When designed well, they can modernise systems, improve efficiency and support long-term economic resilience.

Extreme weather is becoming an expensive norm

Between 2021 and 2024 alone, extreme weather events cost Europe an estimated €40–50bn annually. Over the longer period from 1980 to 2024, direct economic losses reached around €822bn, with recent years accounting for the highest annual losses.

These figures capture only direct losses such as destroyed infrastructure, damaged crops or disrupted transport networks. The wider economic impacts, including supply chain disruptions and long-term productivity losses, further raise the real cost.

The EEA briefing highlights that agriculture, energy and transport sit on the frontline of climate impacts.

Crops are increasingly exposed to droughts and heat stress, power systems face higher cooling demands and risks to generation and grids.

At the same time, transport infrastructure is vulnerable to flooding, heat damage and coastal erosion. As climate extremes intensify, so too does the financial exposure of these critical sectors.

The investment gap in climate adaptation

According to the EEA, making these sectors climate resilient will require a dramatic scale-up in spending.

By 2050, annual investments of between €53bn and €137bn will be needed, depending on whether global warming is limited to 1.5–2°C or rises to 3°C above pre-industrial levels. By 2100, those annual figures could climb to between €59bn and €173bn.

Yet current committed funding for climate adaptation in agriculture, energy and transport is estimated at just €15–16bn per year. Most of this comes from public sources at the EU, national and regional levels, underscoring the challenge of mobilising sufficient private capital.

Without closing this gap, Europe risks locking in higher future losses that will far exceed the cost of acting now.

Why climate adaptation pays off economically

One of the strongest arguments for climate adaptation is its return on investment. Research by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre shows that adapting to rising coastal flood risks in the EU can deliver around €6 in benefits for every euro spent.

At the global level, the World Resources Institute has found that each dollar invested in adaptation can generate more than $10.50 in benefits over a decade, with average project returns of 27%.

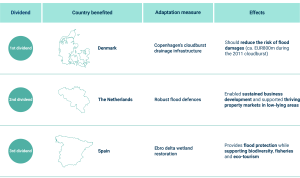

The EEA also points to broader economic frameworks that help explain these gains. Adaptation often delivers a ‘double dividend’ by reducing climate risks while also supporting sustainability or emissions reductions.

Nature-based solutions, such as restoring wetlands, are a prime example, as they protect against floods while storing carbon. In some cases, a ‘triple dividend’ emerges, where adaptation not only avoids losses but also stimulates economic growth and delivers social and environmental co-benefits.

A competitiveness test for Europe

The EEA’s message is clear: delaying climate adaptation will cost Europe far more than acting decisively now.

Investing in climate-resilient agriculture, energy and transport would not only reduce mounting losses from extreme weather but also strengthen food security, safeguard energy systems and improve the reliability of transport networks.

As climate risks grow, Europe’s ability to adapt will increasingly shape its economic performance. Climate adaptation, once seen as a secondary policy goal, is rapidly becoming a cornerstone of Europe’s future competitiveness.