After 20 years of thorough planning and preparation, the European Space Agency’s (ESA) EarthCARE mission is now in flight and has already produced interesting data. We spoke to Mission Manager Björn Frommknecht to find out more.

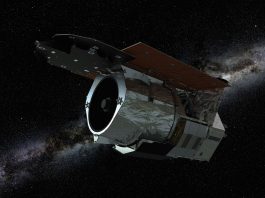

Launched in 2024, ESA’s EarthCARE mission is designed to make global observations of clouds, aerosols and radiation and revolutionise our understanding of how these factors affect our climate. EarthCARE aims to quantify cloud-aerosol-radiation interactions so they may be included correctly in climate and numerical weather forecasting models. To achieve its objectives, the satellite has four instruments and measures globally the vertical structure and horizontal distribution of cloud and aerosol fields together with outgoing radiation.

The EarthCARE satellite successfully embarked on its journey into space on 29 May 2024, aboard a Falcon 9 rocket from the Vandenberg Space Force Base in California, USA. Following the commissioning phase, the first stage of data was released to the public in January 2025.

To learn more about the significance of the mission, its complexities, and the findings so far, Editor Georgie Purcell spoke to Björn Frommknecht, EarthCARE Mission Manager.

Can you briefly summarise the EarthCARE mission and its main objectives?

EarthCARE is a collaboration project between the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). The main objective of the EarthCARE mission is contained in the name: it is an Earth observation mission, and the CARE stands for Cloud, Aerosol, and Radiation Explorer.

We are investigating the role of clouds and aerosols and their interaction with radiation from the Sun, as well as radiation from the Earth. To accomplish that, we fly four instruments – an atmospheric LiDAR (ATLID), a cloud profiling radar (CPR), a multispectral imager (MSI), and a broadband radiometer (BBR). One of the active sensors, the cloud radar, was gifted to us by JAXA. Collaboration between space agencies and the instruments is imperative to this mission.

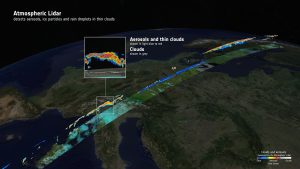

The image here uses data from 18 September and shows how the satellite’s atmospheric lidar detects aerosols and ice particles in thin clouds

EarthCARE is very special for a number of reasons. The mission was selected in 2004, so it has been a long time in the making. It is a really cutting-edge technology and, today, ESA is the only agency to fly such an atmospheric LiDAR in space. We are advanced in Europe, and that is something we can be really proud of. This achievement has only been possible because of the excellent EarthCARE team efforts, facing many challenges. I have never met a team with more dedication, integrity, and professionalism than the EarthCARE one. Of course, the collaboration with JAXA has also helped us significantly, as well as collaboration with European industry.

Over the years, the mission has faced critical delays caused by major events, such as the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami that destroyed a chip factory where part of the cloud profiling radar was built, delaying the project by several years. Another challenge was caused by the war in Ukraine, as the launch was originally planned to be on a Russian Soyuz rocket, which was thus no longer available. After an intense testing process, we instead launched on the SpaceX Falcon-9 rocket successfully.

Why is it so important to shed light on the role that clouds and aerosols play in regulating Earth’s climate?

For predictions of how the Earth’s climate will evolve, you must make certain assumptions about cloud and aerosol behaviour, interaction with solar radiation and the thermal radiation of the Earth. However, there is still a lot of uncertainty surrounding this. Any improvement we can make in terms of this uncertainty has an immediate benefit on the climate model accuracy, especially for long-term predictions.

What is the significance of the four instruments used for the mission?

We have two active sensors, which emit radiation and can actively scan targets. The atmospheric LiDAR is like a laser pointer that emits UV light to measure distances and detects and profiles aerosols such as dust clouds, industrial pollution, sea water, and vapour. The profiling capability allows to discover their vertical structure.

The cloud profiling radar is similar, but for the clouds – it can detect clouds and see their inner structure. It can detect vertical motion, so you can see if things inside the cloud move away or towards the satellite. If it moves away, that is precipitation. This means that we can see where it rains inside a cloud. This is also very important information for numerical weather prediction.

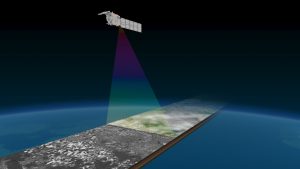

To classify the profiles further, we have a multispectral imaging instrument. The width of the field of view of these active sensors, known as the swath, is relatively small (1km for the cloud profiling radar and 30m for the LiDAR). The imager, which has a swath of 150km, allows us to gather more contextual information.

The fourth instrument is the radiometer. At the very end of the processing chain, we expand the vertical profiles with the small footprint to a cube of 10x10km and 10km high and simulate what the radiation at the position of the satellite would be if our assumptions on how the clouds and aerosols interact with the radiation from the Sun and Earth were true. A major strength of EarthCARE is that these four sensors measure in the same place at the same time. Previous missions from other major space organisations, such as NASA’s A-train, have used several sensors on different satellites, flying one after the other. However, as the weather changes very quickly, even just a few seconds can make a difference. We are the only ones that can measure all that in one instance, in one place. We then compare the radiation that is measured to the one we think should arrive at the position of the satellite. From this difference, we can then improve our understanding of how the clouds and aerosols interact with the radiation. This information can then be fed into both the weather and climate models.

What have been the key findings from the mission so far?

In October last year, we published synergistic images. These demonstrate that, only by using both active sensors together, you can gain a full picture of clouds and aerosols, including their structure and the radiative part. Already, we have been able to see where the atmosphere heats or cools the Earth’s climate. This is a preliminary result achieved just six months after launch, but the scientists are already very excited. This is a proof of concept that both the quality of the sensors is as expected and that there is a very high probability that we will get the scientific results we are aiming for. The public release of Level-1 data started in January, with Level-2 data following in March. Already, the results are very promising.

Have you encountered any difficulties since the launch? If so, how have they been overcome?

One of the main challenges directly after the launch was the preparation for our calibration and validation campaigns. We must externally validate and calibrate our measurements, which we can achieve by using planes that fly under the satellite. The satellite is much faster than a plane – it flies at 7km per second, whilst the plane flies at around 900km per hour. You must be in the right place at the right time. We had six major calibration campaigns, which were a collaboration of many European countries and the US. It was a monumental effort and a very nice example of collaboration.

EarthCARE’s multispectral imager for wide-scene context

These campaigns require careful and thorough planning. We had very well-defined target dates for the instruments to be ready to compare measurements. That was a major challenge. The preparatory phases for the radar, imager and radiometer were quite quick and we ran ahead of schedule, but the ATLID was ready with just one day margin. That was a very interesting and very intense experience. Again, it was an excellent collaboration between industry, ESA, and JAXA.

For the ATLID, certain steps must be followed to ensure that the light reflected by the aerosols is centred in the receiving telescope, thus maximising the measurement quality. This was successful and the instruments were so well calibrated that the on-ground and airborne equipment then had to be readjusted.

What’s next for the mission? When is it expected to end?

The first batch of Level-2 data was released on 17 March. These are single-sensor and two-sensor products. The further you go down in the processing chain, the more sensors you combine to generate products. Before the end of the year, we will release the full synergistic products, with three- and four-sensor synergy. These are the next major milestones.

As we have to fly relatively low, meaning 400km in height, our life-limiting factor is the propellant usage. The nominal mission lifetime is three years from launch, which would bring us to May 2027, but we have indications that the lifetime could be extended, subject to our Member States’ approval, which we hope to obtain.