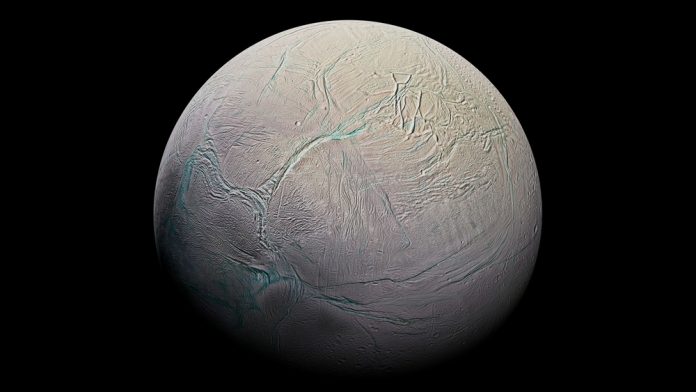

NASA’s Cassini mission has revealed an astonishing new chapter in the story of Enceladus, Saturn’s icy moon long regarded as one of the Solar System’s most promising locations for extraterrestrial life.

For the first time, scientists have detected significant heat flow from both poles of the moon – evidence that its internal energy system is stable and sustainable over geological timescales.

The breakthrough, led by researchers from Oxford University, the Southwest Research Institute, and the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, suggests that Enceladus moon is far more thermally active than previously believed.

This finding bolsters the idea that it could maintain a habitable subsurface ocean capable of supporting microbial life.

Heat flow beyond the south pole

Until now, scientists thought Enceladus’ warmth was confined to its dramatic south pole, where icy geysers shoot plumes of water vapour and organic molecules into space.

But new data from Cassini’s infrared instruments show that the north pole, once considered dormant, is losing heat too – a revelation that fundamentally changes our understanding of the moon’s energy balance.

Using Cassini’s observations from 2005 (northern winter) and 2015 (northern summer), the team measured how much energy escapes through Enceladus’ icy crust.

Surprisingly, the surface at the north pole was around seven degrees Kelvin warmer than expected, implying that heat from the subsurface ocean is leaking through the ice shell.

The researchers estimate that the north pole alone emits about 46 milliwatts per square metre, roughly two-thirds of the average heat flow through Earth’s continental crust.

When scaled across the entire moon, this equates to around 35 gigawatts of energy – comparable to the output of more than 10,000 modern wind turbines.

Balancing heat and habitability

When this newly detected heat loss is combined with the known activity at Enceladus’ south pole, the total energy output rises to approximately 54 gigawatts.

This figure closely matches theoretical predictions for heat generated by tidal forces – the stretching and squeezing effect caused by Saturn’s immense gravity as the Enceladus moon orbits the planet.

This balance between heat production and energy loss is vital. If the moon radiated energy too quickly, its underground ocean might freeze solid; if it generated too much, it could trigger instability and alter the chemical environment needed for life.

The new findings suggest that Enceladus has maintained a stable thermal equilibrium for millions of years, allowing its global ocean, rich in salts, phosphorus, and complex organic molecules, to remain liquid and potentially habitable.

A prime target in the search for life

Among all the ocean worlds in our Solar System, the Enceladus moon now stands out as one of the most promising for life beyond Earth.

Cassini’s previous flybys detected plumes of water ice and vapour laced with organic compounds, hinting that the ocean beneath the ice may contain the essential ingredients for biology: water, heat, and chemical energy.

The discovery of balanced heat flow across both poles strengthens the idea that this environment is not only present but stable – a crucial condition for life to emerge and persist.

The study’s authors emphasise that understanding the moon’s long-term energy budget is key to assessing its true habitability.

Mapping the ice and planning the future

In addition to identifying global heat flow, the research also offered new insights into Enceladus’ ice shell.

Using thermal data, the team estimated that the ice is between 20 and 23 kilometres thick at the poles, with a global average of about 25 to 28 kilometres – slightly deeper than earlier models suggested.

These measurements will be critical for designing future missions that aim to sample or even penetrate the subsurface ocean.

Although Cassini’s mission ended in 2017, its data continues to yield groundbreaking discoveries years later.

The researchers note that detecting such subtle temperature variations – just a few degrees above the frigid surface average of –223°C – required the spacecraft’s long-term observations spanning over a decade.

The next chapter in exploration

The study underscores the importance of future missions dedicated to ocean worlds like Enceladus.

Robotic landers or cryobots designed to drill through its icy shell could directly sample material from the ocean below, providing definitive answers about the presence of life.

For now, this new evidence of balanced heat loss marks a pivotal step forward. The Enceladus moon – once dismissed as a frozen, lifeless world – is emerging as one of the most intriguing and potentially habitable destinations in our Solar System.