This article describes the scientific motivation and high-level concept for a warning system for advanced space weather prediction with increasing accuracy.

As humanity’s reliance on microelectronics and orbital infrastructure reaches critical levels, our civilisation faces an unprecedented vulnerability to solar volatility. While the original Dyson sphere was a thought experiment in energy harvesting, the “new Dyson sphere” is a pragmatic necessity for planetary defence: a distributed, interplanetary framework of information-capture constellations.

By integrating multipoint spacecraft clusters, standardised mass-produced units, and real-time AI forecasting, this proposed system moves beyond the 30-minute warning window of current Lagrange-1 point monitors. It offers a paradigm shift in heliophysics – providing the 12-hour lead times essential for stabilising global power grids, protecting satellite networks, and ensuring the safety of Artemis and Mars explorers. This article outlines the scientific breakthroughs in Kelvin-Helmholtz wave detection and the industrial standardisation required to turn space weather from a trillion-dollar threat into a manageable operational event.

Introduction

Sixty-four years ago, physicist Freeman Dyson proposed a thought experiment that became a staple of science fiction: an advanced civilisation, hungry for energy, would eventually construct a vast spherical shell around its host star to capture every photon of its output (Dyson, 1960). This “Dyson sphere” was a monument to industrial consumption.

While the modern AI-infrastructure and prospective future demand require ever-increasing power sources, today, humanity faces yet an additional challenge. We are not yet needing to harvest the Sun’s total energy, but we desperately need to understand its dynamical temper, as well as the structure and dynamics of its expanding atmosphere – the solar wind, and how it gets further modified when encountering planetary magnetospheres. We have built a global civilisation that is profoundly interconnected and entirely dependent on microelectronics and near-Earth orbital infrastructure. From global financial transactions and just-in-time supply chains to the GPS signals that guide transport and the satellite constellations providing broadband to the developing world, the central nervous system of modern society is electrical.

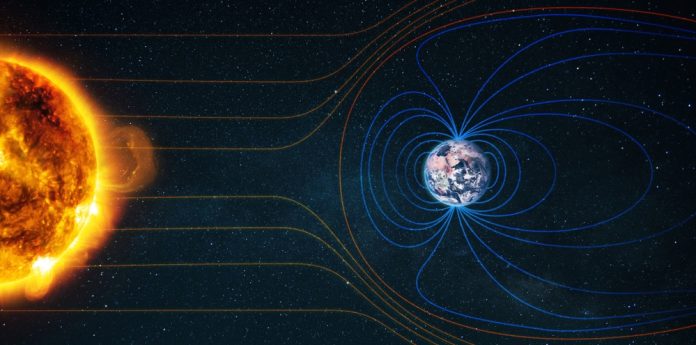

The Sun is not a steady light bulb; it is a dynamic, electromagnetic fusion reactor, controlled by gravity, that semi-periodically ejects billions of tons of plasma – Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs) – hurtling across the solar system at millions of miles per hour. When these electromagnetic solar storms with plasma and energetic particles strike the Earth’s magnetosphere, they can induce geomagnetically induced currents (GICs) in power grids, killing transformers, frying satellite electronics, disrupting radio communications, and leading to high fluxes of space radiation at aviation altitudes.

The historical record offers stark warnings. The 1859 Carrington Event, a severe geomagnetic storm, if it occurred today, would produce major havoc to our orbital infrastructure, communication and navigation systems, power grids and pose a danger to aviation safety. In 2025, the LLoyd’s of London published its report estimating that, if Earth was hit by an extreme solar storm the global economy could be exposed to losses of $1.2-9.1 trillion (depending on the severity of the storm) over a five-year period, with North America identified as the region likely to be most financially impacted by the scenario (https://www.lloyds.com/insights/media-centre/press-releases/extreme-space-weather-scenario). In 1989, a major geomagnetic storm (the largest of the last century) caused widespread effects on power systems, including a blackout of the Hydro-Québec system. In 2012, an extreme solar superstorm missed the Earth, which could have produced large radiation exposure to airline passengers and jeopardised other infrastructure for weeks.

Even moderate space storms can be harmful when launching spacecraft into low-Earth orbit (see e.g., Baruah et al., 2024 and references therein). In February 2022, 38 Starlink satellites were destroyed before reaching the desired altitude due to increasing atmospheric friction because a geomagnetic storm increased heating and raised the atmosphere to higher altitudes (Lin et al.,2022; Fang et al.,2022). The cost was estimated to be around $30 million to $50 million when factoring in the launch costs.

Yet, our primary defence against this existential threat relies on an observational system of a few spacecraft, positioned closer to the Sun and at the Sun-Earth Lagrange Point 1 (L1), just one million miles upstream – a mere stone’s throw in cosmic terms. Missions like ACE, Wind, DSCOVR and the new IMAP and SWFO-L1 provide invaluable data, but for the fastest, most destructive solar storms, they offer a warning window of perhaps 30 to 60 minutes. In the context of grid operator reaction times or satellite safe-mode protocols, this is insufficient.

The Mother’s Day space storm – Why it was the largest since 2003

A major difficulty in space weather prediction is the dynamic evolution of the solar wind and its transients (e.g., CMEs and Corotating Interaction Regions, CIRs) that occurs during traversal from Sun to Earth. The space weather processes and solar wind-magnetosphere coupling efficiency are strongly determined by the orientation of the interplanetary magnetic field (IMF) and solar wind speed.

It is well known that most efficient energy and magnetic flux loading into the Earth’s magnetosphere occurs during the dayside magnetic reconnection when IMF, carried by the solar wind, is pointing to the opposite, “southward” (Bz < 0) direction than the Earth’s mainly dipolar, “northward” (Bz > 0) field in the dayside magnetopause. During these southward IMF conditions, the dayside reconnection peels off the Earth’s magnetic shield like layers of an onion, transporting the magnetic flux to the night side of the planet (Dungey, 1961), leading to cumulation of magnetic tension into the Earth’s magnetotail – an elongated teardrop-shaped region generated by stretching of the geodipole by the solar wind flow.

Once the magnetotail can’t hold more magnetic tension, like a pulled rubber band, it breaks, springing forward toward the planet. This is called magnetotail reconnection, and if it occurs across the tail, it leads to global re-organisation of the magnetosphere, the so-called geomagnetic substorm. The beautiful consequence of this is the rapidly dancing Aurora close to the northern and southern geomagnetic poles. The negative consequences are the strong variations of the Earth’s magnetic field, which can lead to the generation of GICs (Viljanen et al.,2001), which can bring down the power delivery networks (Pulkkinen et al., 2003).

During a geomagnetic storm, which can occur over several days when a CME hits the Earth, several substorm cycles occur, resulting in heating and acceleration of tail plasma toward the ring current – a ring-shaped current formed by energetic positively charged ions moving clockwise and negatively charged electrons moving anti-clockwise, when viewing from north.

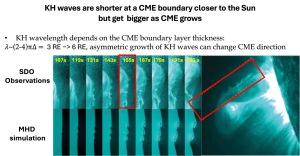

The tail reconnection forms a tenuous and hot plasma in the magnetotail “plasma sheet”, a layer of plasma carrying the cross-tail current which separates the tail lobes with opposite magnetic polarities. On the other hand, during prolonged northward IMF conditions, the plasma sheet becomes filled with cold and dense solar wind material (see e.g., Wing et. al., 2005; Oieroset et al., 2005 and reference therein). It has been shown that at the dayside this can be produced by double high-latitude reconnection (Taylor et al., 2008; Li et al., 2009), and at flank boundaries by magnetic reconnection, driven by large-scale (3-6 RE) waves, so-called Kelvin-Helmholtz (KH) waves (Nykyri and Otto, 2001; Ma et. al., 2017). The KH waves can be frequently seen at the interface of two fluids that exhibit a velocity shear, e.g., mountain cloud waves, or when water passes a rock in the river.

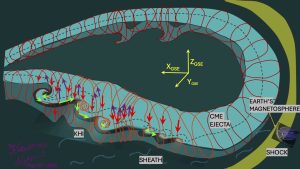

The “Mother’s Day” space storm (also called the Gannon storm), which was the largest since the Halloween storm in 2003, was amplified by the giant 60-250 RE KH waves at the boundaries (see Figure 1) of the coronal mass ejections (CME) that had southward field in the ejecta and hurled out to interplanetary space on May 8, 2024. These waves were detected at L1 satellites and by NASA’s ARTEMIS spacecraft at lunar orbit in the solar wind and by NASA’s four Magnetosphere MultiScale (MMS) spacecraft. As the draped field around the southward ejecta field was mostly northward, the KH waves led to a strong and periodic ~ 45 min – 60 minute +- variability of the IMF Bz component and visible vortex (at least 54 Re in size), most clear in the IMF By-component (Nykyri, 2024).

This periodicity exposed Earth’s magnetosphere into several successive magnetic flux loading (stronger during southward IMF) and plasma loading (stronger during northward IMF) intervals into the magnetotail likely explaining the generation of the largest ring current in ~ 20 years (Nykyri, 2024). If the KH waves were not at the boundary, the Earth’s magnetosphere would have crossed the CME shock, entered the CME sheath and then the ejecta with southward field. But since the wave twisted the boundary, the Earth’s magnetosphere ended up surfing the waves periodically. The KH waves also compressed the current layers at the CME boundaries, leading to reconnection and plasma jets with energetic particles (Nykyri et al., 2024,2026). The growth rates and wavelengths were also calculated in this article, using the ARTEMIS data, placing the source region of the KH instability that generated the waves about 7 million km upstream of the Earth-Sun Lagrange 1 point. This was the first study that clearly demonstrated the need to place additional solar wind monitors at 8.5 million km upstream from Earth, allowing 3-5 hours’ advanced predictions of IMF Bz-variability, which could not be determined using spacecraft very close to the Sun or at the Earth-Sun L1 point.

The width and height of the Earth’s dayside (X > 0) magnetosphere and bow shock are about 30-60 Earth radii (RE). The Gannon Storm CME boundary layer twisted by KH waves was wider than the cross-section of the Earth’s dayside magnetosphere, and the wavelength was longer than the magnetotail, even beyond lunar orbit. However, the solar wind often can contain structures comparable to and smaller than the cross-section of the magnetosphere. These intermediate-scale structures are created by various plasma instabilities and waves in the solar wind and might lead to different sides of the magnetosphere encountering solar wind parcels of different properties. However, currently our best space weather models can’t resolve these “intermediate to meso-scale” structures, making accurate predictions of IMF orientation at Earth impossible.

Further complexity arises from various transient structures created by bow shocks in front of the planets (Zhang et al., 2022). For example, It has been shown that large-scale poloidal oscillation in the IMF Bx and Bz can create a substorm during a “northward” interval as detected by L1 monitors, when simultaneously the Bx-phase of the oscillation hits the bow shock generating supersonic magnetosheath jets which can snowplough the pre-existing magnetic field into southward IMF orientation (Nykyri et al., 2019) and trigger dayside reconnection (Hietala et al., 2018). However, together with sub-L1 and L1 monitors and continuous measurements between L1 and Earth (including magnetosheath), one could generate hours in advance accurate predictions when the jet and transient generation in the shock is likely to occur.

The new Dyson sphere

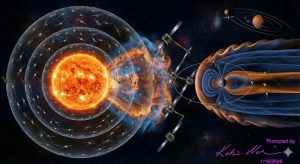

To achieve real-time forecasting of the space weather conditions at Earth a with 2-day, 1-day, 10 hr, 5 hr, 3 hr, 30 min lead time with increasing accuracy, we must populate the vast space between the Sun and Earth at various radial distances with constellations of intelligent spacecraft, utilising optical interspacecraft communications, that can be used to calculate the “perturbation” fields in real-time and provide predictions of IMF Bz and energetic particle bursts (see Figure 2). For the energetic particle prediction, it is not sufficient to just have spacecraft close to the Sun (to measure solar energetic particles, SEPs) as local plasma processes, such as shocks, instabilities, and reconnection, can locally lead to particle acceleration (Nykyri et al., 2024,2025).

This can be achieved by employing the Solar and Earth orbiters at various inclinations and apogee-perigee ratios, as well as using the Mercury, Venus, and Earth Lagrange (L) points, where gravitational forces between the planet and Sun approximately balance each other. The L1 lies in front of the planet; L3 behind the Sun, aligned with the L1; and the L4 (L5), at a 60-degree angle to the right (left) from the Sun-planet line, respectively. For future missions to Mars, this network, together with a constellation at Mars-Sun L1 point, would provide critical forecasts of the radiation environment, i.e., solar energetic particles (SEP) both when astronauts are enroute to Mars and in Mars orbit/surface.

In 2024, the National Academy of Sciences published the Decadal Survey (DS) in Solar and Space Physics (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2025), outlining the heliophysics research strategy and cadence for space mission launches for the next decade. The DS recommended the Solar Polar Orbiter as a strategic heliophysics mission to measure magnetic fields and velocity structure for extended periods at the Sun’s poles. These measurements are required to understand the magnetic dynamo of the Sun during different phases of the solar cycle and would be the first polar mission orbiting the Sun since the joint ESA-NASA Ulysses mission (1990-2009).

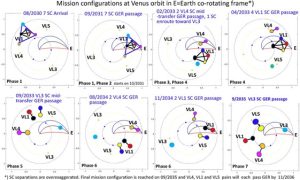

The DS was motivated by 427 white papers, including mission concepts that the heliophysics community submitted to the Academy. The general theme in the white papers was the need for multi-spacecraft solar wind constellations using a combination of in-situ and remote sensing measurements. For example, two such white papers specifically motivated the scientific and operational need to populate the Venus-Sun Lagrange points by 7 spacecraft Seven Sisters-constellation (see Figure 3), which would act between traditional space plasma science missions and as a pathfinder for future operational space weather missions in new locations (Nykyri et al., 2022ab; Nykyri et al., 2023). The DS recommended a formation of a new NASA Explorer class, the Heliospheric Large Explorer (HeLEX) cost-capped between current Medium-Class Explorers and larger-scale Living With a Star and Solar Terrestrial Probe lines, which is ideal for this type of multi-spacecraft mission.

Figure 2 presents an artistic illustration of the “new Dysons sphere” which can be built as an international collaboration between different government agencies, academia and industry. For example, it was estimated (Nykyri et al., 2023) using 2022 dollars that a single Falcon Heavy launch vehicle would be sufficient for sending the Seven Sisters spacecraft toward Venus orbit with reasonable cost (< 600 M USD). To achieve the real-time operational space weather needs, ideally one would increase the launch cadence and lower the mass-to-orbit cost by bringing every 4-6 months both a set of ~3-4 highly-durable science/operational space weather spacecraft for sub-L1 locations and ~3-4 tech-spacecraft driven by pure industry needs, into highly elliptical Earth orbit (e.g., for solar power operated AI data centre infrastructure), maintain the space weather spacecraft there with active propulsion for 6-12 months and then let them naturally drift (while still collecting measurements). When the new replacement units arrive. This would allow continuous, large-scale manufacturing and operation of radiation shielded, standardised spacecraft units, while balancing the manufacturing and launch costs for various stakeholders.

Future operational landscape

As humanity prepares for a permanent presence on the lunar surface through the Artemis programme (and later Mars programme), we are stepping out from under the protective umbrella of the Earth’s magnetosphere against galactic cosmic rays and SEPs. Unlike Earth, the Moon and Mars lack a global magnetic field to deflect high-energy solar particles. For astronauts on the lunar surface or in the Gateway station, an unpredicted Solar Energetic Particle (SEP) event is not just a technical hazard; it is a life-threatening radiation emergency.

The new Dyson sphere acts as a critical safety net for these lunar and Mars pioneers. By positioning sentinel constellations at Mercury-Venus-Earth-Mars-Sun Lagrange points and planetary/Moon orbiters, we can detect the onset (via remote sensing) and evolution (via in-situ particle and field detectors) of a solar eruption hours before the deadly “proton storm” reaches the Earth-Moon-Mars system. In a traditional scenario, astronauts might have minutes to scramble for a radiation shelter. With the New Dyson Sphere, they have tens of minutes (for > 50 MeV protons accelerated close to the Sun) to hours (for trapped pockets of energetic ions that are captured within CME structure and thus arrive together with the CME unless released earlier by reconnection). This lead time allows for the orderly cessation of Extravehicular Activities (EVAs), the shielding of sensitive biological experiments, and the lunar and Mars habitats. We are effectively extending the “situational awareness” of the Artemis missions by millions of miles, ensuring that our return to the Moon and future exploration of Mars is sustainable rather than a gamble against solar volatility.

The “Model T” of interplanetary spacecraft

To make these information-capture shells a reality, we must move away from the “bespoke” era of spacecraft manufacturing. Historically, deep-space missions have been multi-billion-dollar “hand-crafted” boutique projects. The new Dyson sphere requires a “Starlink” approach: the mass-production of Standardised Spacecraft Units (SSUs).

This is the “Model T” moment for heliophysics and safe space exploration. By utilising a standardised chassis – radiation-hardened, modular, and equipped with optical inter-spacecraft communication – we can achieve economies of scale that were previously impossible in interplanetary exploration. These SSUs would be designed for “Hot-Swapping.” Much like an AI data centre replaces faulty servers, we would launch these units in high-cadence cycles (every 4-6 months). If a sentinel is damaged by a solar flare or reaches the end of its propellant life, a replacement is already enroute. This standardisation lowers the “Mass-to-Orbit” cost and allows a diverse group of stakeholders – from national space agencies to private AI infrastructure firms – to contribute to the constellation’s growth and launch costs.

The sentinel in action: A day in the life

Imagine a Tuesday in the near future. At 04:00 UTC, a massive “X-class” solar flare erupts from a complex active region on the Sun, followed by a CME. Within seconds, the innermost sentinels of the New Dyson Sphere in the elliptical solar orbit capture the high-resolution electromagnetic signature, followed by high fluxes of 100 MeV-energy protons. SEP warning and estimated arrival time (04:19:23 UTC) to the lunar orbiting spacecraft is sent and received at 04:08:00 UTC, giving astronauts 11 minutes to seek shelter. The CME plasma hits the first shell of the spacecraft at highly elliptical solar orbits 25 minutes later. The onboard AI doesn’t just relay data; it processes the local plasma density, velocity and magnetic field orientation in real-time. It identifies the growth of Kelvin-Helmholtz waves – the giant waves that can form vortices in space (see Figures 1 and 5) at the CME boundary that can amplify the storm’s impact and locally continue to accelerate energetic particles.

By 04:26 UTC, the onboard intelligent algorithm has used spacecraft “trigger data” and calculated the expected k-vector magnitude and direction and makes a prediction of the IMF Bz variability timescale, magnitude and CME arrival time, which is relayed to the next shells of spacecraft at Mercury orbit and to Lunar base and Earth via an optical laser link. The constellations at Mercury encounter the CME at 09:08:00 UTC and at Venus orbit at 14:00:00 UTC and repeat the calculations, leading to a revised, more accurate forecast which is sent to the lunar base and Earth. While the CME is still 12 hours away, the signal has already arrived. Utility companies in North America have received an automated “Level 5” warning. They begin a controlled “de-loading” of high-voltage transformers, preventing the geomagnetically induced currents that caused the 1989 Quebec blackout. Satellite operators rotate their constellations into a “feathered” safe mode. At Kennedy Space Center, the operators scrub the launch of 50 Starlink satellites to orbit. On the Moon, Artemis astronauts have already finished their breakfast and safely secured themselves in the reinforced core of their habitat. Because of the new Dyson sphere, a potential global catastrophe has been downgraded to a manageable scheduled event.

Please Note: This is a Commercial Profile

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International.

References

- Baruah, Y., Roy, S., Sinha, S., Palmerio, E., Pal, S., Oliveira, D. M., & Nandy, D.(2024). The loss of Starlink satellites in February 2022: How moderate geomagnetic storms can adversely affect assets in low-earth orbit. Space Weather, 22, e2023SW003716.https://doi.org/10.1029/2023SW003716

- Dungey, J. W.(1961), Interplanetary magnetic field and the auroral zones, Rev. Lett., 6, 47–48, doi:10.1103/physrevlett.6.47.

- Freeman J. Dyson, Search for Artificial Stellar Sources of Infrared Radiation.Science131,1667-1668(1960).DOI:1126/science.131.3414.1667

- Fang, T.-W., Kubaryk, A., Goldstein, D., Li, Z., Fuller-Rowell, T., Millward, G., et al. (2022). Space weather environment during the SpaceX Starlink satellite loss in February 2022. Space Weather, 20, e2022SW003193. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022SW003193

- Foullon, C., Verwichte, V. M. Nakariakov, K. Nykyri, and C. J Farrugia(2011), Magnetic Kelvin-Helmholtz instability at the Sun, Astrophys. J. Lett., 729, L8, 4 pp., doi:10.1088/2041-8205/729/1/L8.

- Hietala, H., Phan, T. D., Angelopoulos, V., Oieroset, M., Archer, M. O., Karlsson, T., & Plaschke, F.(2018). In situ observations of a magnetosheath high-speed jet triggering magnetopause reconnection. Geophysical Research Letters, 45, 1732–1740. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL076525

- Li, W., Raeder, M. Øieroset, and T. D. Phan(2009), Cold dense magnetopause boundary layer under northward IMF: Results from THEMIS and MHD simulations, J. Geophys. Res., 114, A00C15, doi:10.1029/2008JA013497.

- Lin, D., Wang, W., Garcia-Sage, K., Yue, J., Merkin, V., McInerney, J. M., et al. (2022). Thermospheric neutral density variation during the “SpaceX” storm: Implications from physics-based whole geospace modeling. Space Weather, 20, e2022SW003254. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022SW003254

- Ma, X., Delamere, P., Otto, A., & Burkholder, B. (2017), Plasma transport driven by the three-dimensional Kelvin-Helmholtz instability. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 122, 10,382–10,395. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017JA024394

- Nykyri, K., & Otto, A. (2001). Plasma Transport at the Magnetospheric Boundary Due to Reconnection in Kelvin-Helmholtz Vortices. Geophysical Research Letters, 28(18). https://doi.org/10.1029/2001GL013239

- Nykyri, K., and C. Foullon (2013), First magnetic seismology of the CME reconnection outflow layer in the low corona with 2.5-D MHD simulations of the Kelvin-Helmholtz instability, Res. Lett., 40, 4154–4159, doi:10.1002/grl.50807.

- Nykyri, K., Bengtson, M., Angelopoulos, V., Nishimura, Y. T., & Wing, S.(2019). Can enhanced flux loading by high-speed jets lead to a substorm? Multipoint detection of the Christmas Day substorm onset at 08:17 UT, 2015. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 124, 4314–4340. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JA026357

- Nykyri, K., Parker, J., De Moudt, L., Rosen, M., Cuellar, R., Herring, M., et al. (2022a). Seven Sisters – a pathfinder mission to protect humanity from space weather. Washington, D.C: National Academies. White paper for decadal survey for solar and space physics (heliophysics) 2024-2033 http://surveygizmoresponseuploads.s3.amazonaws.com/fileuploads/623127/6920789/206-5d12134c82d19aae688488d806a62088_Seven-Sisters-Space_Mission-Concept-Nykyri_NAS_Whitepaper.pdf.

- Nykyri, K., Laxman, A., Argall, M., Borovsky, J., Broll, J., Burkholder, B., et al. (2022b). Critical solar wind measurements required for the next generation space weather prediction mission: Science motivation for the seven Sisters mission. Washington, D.C: National Academies. White paper for decadal survey for solar and space physics (heliophysics) 2024-2033 http://surveygizmoresponseuploads.s3.amazonaws.com/fileuploads/623127/6920789/107-5548346d581dadb6652266d428a79739_WhitePaperScience_v2-2.pdf.

- Nykyri, K., Ma, X., Burkholder, B., Liou, Y.-L., Cuéllar, R., Kavosi, S., et al. (2023). Seven sisters: A mission to study fundamental plasma physical processes in the solar wind and a pathfinder to advance space weather prediction. Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences, 10, 1179344. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspas.2023.1179344

- Nykyri, K.(2024). Giant Kelvin-Helmholtz (KH) waves at the boundary layer of the coronal mass ejections (CMEs) responsible for the largest geomagnetic storm in 20 years. Geophysical Research Letters, 51, e2024GL110477. https://doi.org/10.1029/2024GL110477

- Katariina Nykyri, Neetasha Arya, Scott A. Boardsen, et al. MMS Observations of the Energetic Particles Within Kelvin-Helmholtz waves at the Boundary of the May 2024 Coronal Mass Ejection (CME). Authorea. October 29, 2025. DOI: 22541/au.176176542.21373812/v1

- Øieroset, M., Raeder, T. D. Phan, S. Wing, J. P. McFadden, W. Li, M. Fujimoto, H. Rème, and A. Balogh(2005), Global cooling and densification of the plasma sheet during an extended period of purely northward IMF on October 22–24, 2003, Geophys. Res. Lett., 32, L12S07, doi:10.1029/2004GL021523.

- Pulkkinen, A., Lindahl, A. Viljanen, and R. Pirjola(2005), Geomagnetic storm of 29–31 October 2003: Geomagnetically induced currents and their relation to problems in the Swedish high-voltage power transmission system, Space Weather, 3, S08C03, doi:10.1029/2004SW000123.

- Taylor, M. G. G. T., et al. (2008), The plasma sheet and boundary layers under northward IMF: A multipoint and multi-instrument perspective, Space Res., 41, 1619–1629.

- Viljanen, A., H. Nevanlinna, K. Pajunpa¨ a¨, and A. Pulkkinen (2001), Time derivative of the horizontal geomagnetic field as an activity indicator, Ann. Geophys., 19, 1107 — 1118.

- Wing, S., R. Johnson, P. T. Newell, and C.-I. Meng(2005), Dawn-dusk asymmetries, ion spectra, and sources in the northward interplanetary magnetic field plasma sheet, J. Geophys. Res., 110, A08205, doi:10.1029/2005JA011086.

- Zhang, H., Zong, Q., Connor, H. et al.Dayside Transient Phenomena and Their Impact on the Magnetosphere and Ionosphere. Space Sci Rev 218, 40 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-021-00865-0

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2025. The Next Decade of Discovery in Solar and Space Physics: Exploring and Safeguarding Humanity’s Home in Space. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/53. (https://nap.nationalacademies.org/resource/27938/interactive/