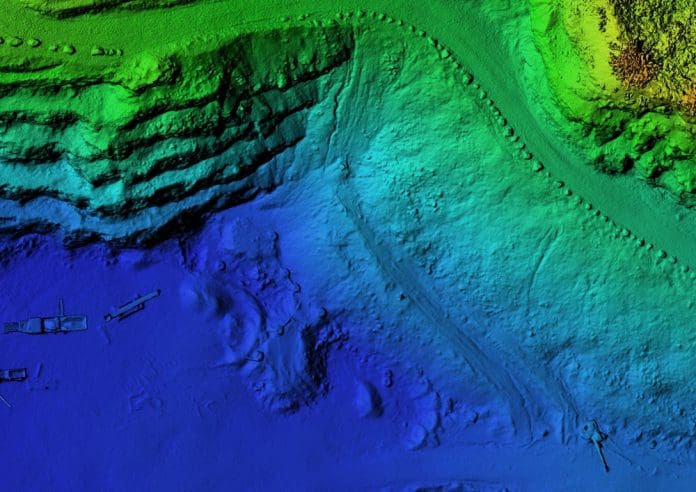

On remote island, Tristan da Cunha, high-resolution satellite and drone imagery are integrated to create accurate digital elevation models.

Medium resolution global digital elevation models (DEMs), such as SRTM and ASTER GDEM, have supported geoscience research for over two decades. However, many environmental and hazard-related applications—including landslide risk, floods, and surface process modelling—require more detailed and more accurate terrain data. Airborne LiDAR or photogrammetric flights can achieve sub-decimetre accuracy but are expensive, logistically difficult, or impossible to use in remote environments. As a result, high-resolution DEMs derived from very high-resolution (VHR) satellite and low-altitude drone imagery are increasingly important alternatives.

Sensor characteristics and terminology

Spatial resolution terms for ground sampling distance (GSD) vary across domains, but this study adopts the following definitions:

- Low resolution: >30m

- Medium resolution: 30–5m

- High resolution: 5–1m

- Very high resolution (VHR): <1m

Drone imagery, with a GSD roughly an order of magnitude finer than VHR satellites, is treated as a separate ultra-high resolution category.

Despite medium resolution spectral imagery from Landsat or Sentinel missions, global DEMs still rely heavily on SRTM and ASTER, both of which contain artifacts, voids, and alignment issues. This motivated the creation of improved products, such as void freed 90m DEMs and commercial datasets like Airbus WorldDEM. While commercial DEMs provide higher accuracy, they remain costly.

Evolution of satellite-derived DEMs

Stereo DEM extraction from spaceborne images began with cross-track SPOT acquisitions. Modern satellites (e.g., WorldView 2/3) now provide in-track stereo, more favourable acquisition geometry, and panchromatic GSD as fine as 0.3m. They also include highly accurate orbit/attitude information, yielding absolute geolocation around 5m CE90. Combined with powerful algorithms such as semi-global matching (SGM), they can produce dense and detailed surface models.

Drone photogrammetry advances and limitations

Low-cost drones with consumer cameras and GNSS/IMU systems have become common for small area mapping. These systems generate extremely dense point clouds—hundreds of points per square metre—but absolute positioning remains weak because of uncorrected GNSS and unstable camera calibrations. Strong image block geometry and ground control points (GCPs) are essential for reliable height accuracy.

Study goal and context

The research investigates the integration of VHR satellite imagery and drone data to produce accurate high-resolution DEMs for Tristan da Cunha—one of the world’s most isolated inhabited islands. The island cannot be mapped using conventional airborne photogrammetry due to its extreme distance from major landmasses. Additionally, harsh weather, steep topography, and frequent cloud cover complicate both satellite and drone acquisition. A newly established geodetic control network on the island within the only settlement provided a precise ground reference necessary for accurate DEM generation.

Data and study site

Tristan da Cunha is a near circular island of ~12km diameter, covering ~96 km² and rising sharply from sea level to Queen Mary’s Peak at 2062m. It lies in the central Atlantic Ocean and is inaccessible by aeroplane. Available datasets include:

- SRTM and ASTER DEMs, both containing noise and voids

- DigitalGlobe/Maxar VHR archives (QuickBird, WV2, WV3)

- Drone imagery from two DJI Phantom 3 missions

- Highly accurate GCPs from GNSS/total station surveys

SRTM and ASTER were fused using BAE’s terrain merge method to produce a medium resolution DEM (mDEM), later used as initial seed data for stereo matching. Of 94 satellite scenes, three were chosen as the core ‘image triplet’ and ten more for the settlement area, selected based on cloud cover, radiometric quality, viewing geometry, and base height ratio (~0.6).

Drone flights generated 373 images with strong geometric diversity. Nine precisely measured GCPs ensured accurate georeferencing.

Methodology

Satellite processing

Photogrammetric workflows were executed independently in three commercial packages:

• BAE SocetGXP

• Hexagon Erdas Imagine

• PCI Geomatica

The general process included tie point generation, triangulation, and terrain extraction via NCC, NGATE, ATE, or SGM algorithms. Matching was performed hierarchically, starting from 30m seed DEMs and iteratively refining to 10m, 5m, 2m, and 1m GSD.

Drone processing

Pix4D Mapper handled self-calibration, triangulation, and point cloud generation. Multiple GCP configurations were tested.

Data fusion

Spaceborne and drone point clouds were merged by direct geodetic alignment, with ICP based comparisons used only for validation.

Results

Satellite triangulation and DEM quality

WV2 and WV3 scenes showed excellent initial geolocation, with residuals under 0.5m—better than published specifications. Only one GCP and one checkpoint were needed to refine the block.

DEM performance varied:

• SocetGXP ATE: Cleanest 2m DEM

• SocetGXP NGATE: Denser but noisier 1m DEM

• Erdas eATE: Low noise, comparable quality

• SGM (Erdas): Extremely dense (~1m spacing) but required heavy noise filtering

• PCI Geomatica: High-quality 2m DEM from the best stereo pair; adding more images increased noise due to temporal differences.

Drone triangulation and accuracy

Without GCPs, drone GNSS yielded strong planimetry but weak height accuracy. With nine GCPs, residuals fell to centimetre levels in all components. The dense point cloud achieved >500 pts/m² in the harbour area and a little less within the settlement..

Integration and comparison

The geodetic control enabled near-perfect alignment between satellite and drone-derived data without rotations or scale corrections. ICP showed:

• Average offset: 0.26m → 0.14m after minor translation

• Height differences: .01m avg, 0.22m std. dev.

The merged product covers the island at ~1–2m resolution, with centimetre-level detail in the harbour.

Conclusions

The study demonstrates that:

1. VHR satellite imagery can reliably replace airborne mapping in remote regions when carefully selected and processed.

2. Image selection (geometry, radiometry, cloud cover, temporal proximity) matters more than matching algorithm choice.

3. Drone photogrammetry provides extremely fine local detail when supported by high-quality GCPs and robust block geometry.

4. Combining satellite and drone data produces complete, accurate, multi-scale DEMs, even under challenging environmental conditions.

Future work should exploit multi-view stereo across larger satellite subsets for better completeness in steep terrain and use multi-temporal satellite archives for hazard monitoring and change detection. Drones will continue to provide ultra-high resolution detail where needed.

Acknowledgment

This project was funded by the University of Luxembourg and carried out by Dr Dietmar Backes and Prof Felicia Teferle. The full article of this Space contribution is accessible at https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2020.00319 and forms part of the doctoral dissertation of Dr Backes.

Please Note: This is a Commercial Profile

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International.