US Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy is expected to announce fast-tracked plans this week for building a nuclear reactor on the Moon.

This announcement marks a significant step toward ensuring the United States remains at the forefront of the increasingly competitive international push to establish a lasting presence on the lunar surface.

Although NASA has long entertained the idea of placing a nuclear power source on the Moon, the latest directive – outlined in internal documents obtained by POLITICO – outlines a concrete, accelerated timeline.

The goal: launch a fully functional 100-kilowatt lunar nuclear reactor by 2030.

A race against time and rivals

This development comes as NASA faces sweeping budget cuts, including nearly a 50% reduction in funding for science missions.

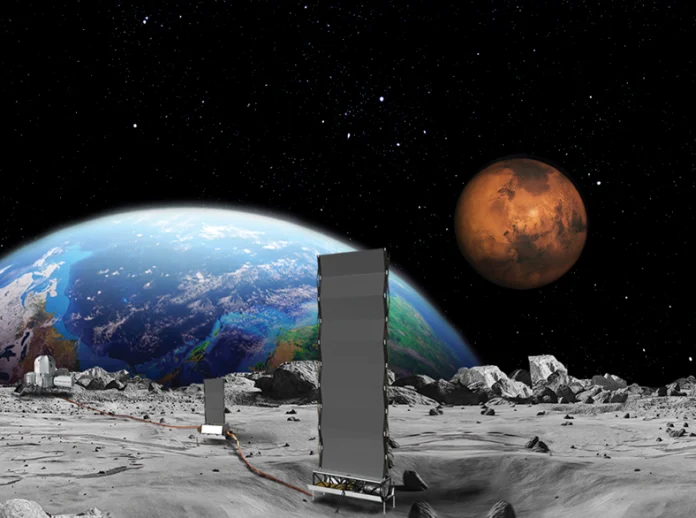

At the same time, the agency is being urged to replace the ageing International Space Station (ISS) and focus its attention on missions that align with the strategic goals of US space policy – particularly human spaceflight to the Moon and Mars.

The urgency of this initiative stems from rising geopolitical competition in space. China and Russia have already announced plans to jointly build an automated nuclear power station on the Moon by 2035.

India, Japan, and Russia are also making rapid progress in lunar exploration. The US aims to beat these nations to deploying a nuclear reactor, which officials warn could be used to declare “keep-out zones” and establish territorial dominance on the Moon.

Why nuclear? Solar won’t cut it

A key technical driver for the lunar nuclear project lies in the unique challenges posed by the Moon’s harsh environment.

A single lunar day spans about 28 Earth days – two weeks of sunlight followed by two weeks of darkness.

This makes relying solely on solar energy impractical for sustaining long-term lunar missions, especially for powering habitats, scientific experiments, and rovers.

Developing a nuclear reactor on the Moon offers a stable, long-lasting solution. It provides a continuous energy supply regardless of lunar day-night cycles, which is vital for supporting a human presence on the Moon and eventually on Mars.

Past progress, future deadlines

NASA has already laid some of the groundwork. In 2022, the agency awarded three $5m contracts to US companies to design concept models for a lunar fission reactor.

The goal of those contracts was to create a compact, efficient system weighing less than six metric tonnes and capable of generating at least 40 kilowatts of power – enough to support basic operations of a small lunar outpost.

These early designs, part of NASA’s Fission Surface Power Project, also considered safety, automation, fuel types, and remote operations. Each partner proposed different innovative concepts, contributing to a diverse portfolio of potential solutions.

Now, the new directive expands that vision. It calls on NASA to solicit new industry proposals for a more powerful 100-kilowatt nuclear reactor on the Moon and to designate a leader to oversee the programme.

The directive also mandates industry feedback within 60 days — a sign that timelines are being significantly shortened to match rising strategic concerns.

Powering the next era of lunar exploration

The plan to deploy a nuclear reactor on the Moon represents a critical step in the United States’ strategy to establish a long-term, self-sufficient presence beyond Earth.

As international competition intensifies, dependable power infrastructure will be essential for supporting lunar operations, from habitats and mobility systems to scientific research and communication networks.

With a targeted launch by 2030, this effort reflects a broader shift toward durable, scalable solutions for off-world exploration.

The reactor project not only addresses the technical challenges of lunar energy generation but also strengthens the US position in shaping the rules and technologies that will define the next phase of space development.

In building a reliable power source for the Moon, the US can reinforce its role as a leader in space innovation and set the stage for future missions that will carry human exploration even farther into the Solar System.