Over recent years, several satellites have engaged in unexplained, uncoordinated close approaches to commercial and military space objects. When satellites are manoeuvring near others in Earth orbit, how close is too close?

In December 2025, a satellite launched from China’s Jiuquan Satellite Launch Centre came within 200m of a SpaceX Starlink satellite orbiting at 560km altitude. No collision occurred, but no coordination between operators had taken place, no orbital data had been shared, and the close approach could have been avoided. This is not an isolated incident. In mid-2024, a satellite from another state moved to within one kilometre of an Indian military mapping satellite. Indian authorities described this as an aggressive move to test their capabilities.

Over recent years, Russian Luch ‘inspector’ satellites have continued a pattern of unexplained, uncoordinated close approaches to Western satellites in geostationary orbit. These incidents highlight an unresolved and pressing question for the wider space community: when satellites are manoeuvring near others in orbit, how close is too close?

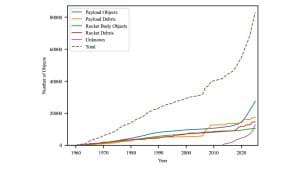

2025 saw record levels of space activity, with over 300 successful launches and an estimated 4,500 payloads reaching orbit. Earth orbit is becoming increasingly congested, with 13,000 active satellites sharing space alongside an estimated 141 million debris objects. This rise in orbital population is matched by increasing satellite sophistication, particularly in Rendezvous and Proximity Operations (RPO). RPOs are orbital manoeuvres in which two spacecraft arrive at the same orbit and approach at close distance, potentially followed by docking.

Despite these technical developments, the governance framework managing human activity in space remains frustratingly vague about what constitutes acceptable behaviour in this crowded environment. This discussion examines issues arising from satellites operating in close proximity, particularly non-consensual RPO missions, and asks when operations cross the line from legitimate activity to interference with other space users.

Consensual vs non-consensual operations

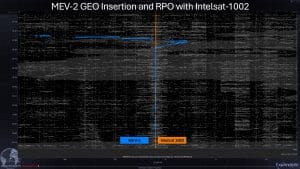

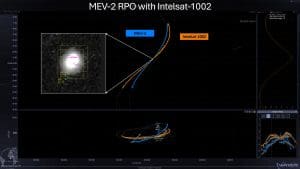

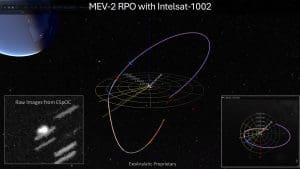

RPO activities can be divided broadly into two categories. Consensual operations involve advanced coordination with clear goals and mutual agreement. In 2020, Northrop Grumman’s MEV-1 became the first commercial spacecraft to telerobotically dock with another in geostationary orbit, extending Intelsat 901’s operational life through transparent, publicly announced missions with regulatory approval.

China’s Shijian-21 demonstrated similar technical capabilities in 2022, docking with and towing the defunct BeiDou-2 G2 satellite to graveyard orbit, though without the advanced transparency characterising MEV missions. More recently, RPOs have become central to Operation Olympic Defender, the multinational coalition coordinating space defence operations among the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, France, Germany, and New Zealand.

Non-consensual operations can be defined as one satellite approaching another without notification or declared intent. The Russian Luch satellites exemplify this concern. In September 2018, France’s Defence Minister accused a Luch-Olymp spacecraft of espionage after it manoeuvred close to the Athena-Fidus military communications satellite.

Luch-2 has recently approached various commercial and military satellites in geostationary orbit. Russia describes these as ‘inspector’ satellites, but the lack of transparency about missions and objectives transforms potentially legitimate technology development into behaviour that increases suspicion and hostility.

This tension between operational transparency and the need to ensure the safeguarding of information for national security creates dangerous unpredictability. Unless nations and commercial operators communicate their intentions, uncertainty will fuel international tensions and instability.

Why ‘close’ defies simple definition

In answering the question ‘how close is too close’, a simple numerical threshold would appear to offer tempting certainty. For example, a 10km perimeter around each satellite incursion into which is ‘too close.’ Unfortunately, orbital mechanics make this proposition more complicated.

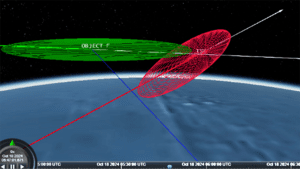

Space Situational Awareness (SSA) providers use radar and optical telescopes to track objects, producing conjunction data messages (CDMs) that predict potential collisions. However, tracking data contains inherent uncertainty that grows with time since the last observation. Orbit determination produces uncertainty ellipsoids. These are three-dimensional regions where objects are most likely located. When ellipsoids intersect, operators measure ‘miss distance’ to determine collision risk.

These calculations fail to account for satellite physical dimensions and must consider relative velocity. A 1km approach at low velocity may pose a greater risk to a satellite than a 5km approach at high velocity. This complexity informs how operators define risk thresholds. The Space Data Association survey found geostationary orbit operators use miss distance thresholds ranging from 1-15km, while low Earth orbit operators range from 100m-1km, with many relying on collision probability calculations.

Tracking quality varies with altitude and object size. Geostationary orbit benefits from stable optical tracking, while low Earth orbit relies on radar complicated by atmospheric drag, particularly for small objects. As mega-constellations proliferate, conjunction alerts multiply—the first weeks of 2026 saw 1,500 CDMs published, over 80% involving low Earth orbit objects.

Different orbits, risk tolerances, and evaluation strategies mean simple boundaries provide only partial solutions. Breaching notional perimeters matters only with hostile intent, and determining intent is not straightforward.

The intent problem and dual-use dilemma

The majority of proximity operations are routine, necessary and cooperative. Geostationary satellites drift kilometres during station-keeping; atmospheric drag causes unpredictable convergence in low Earth orbit. However, distinguishing deliberate operations from malfunction requires careful analysis of controlled relative motion, planned manoeuvre sequences, and stable position-keeping.

These technical indicators can identify behaviour, but not motivation. Ground-based systems track what satellites do, but dependant on the orbital regime and ground-based capabilities this is rarely persistent tracking. Additionally, it can be a struggle to distinguish between onboard failures, operator decisions, or mission objectives. The most reliable indicator of benign intent remains advance notification and transparent communication, and this is precisely what distinguishes the MEV missions and Operation Olympic Defender from Luch activities.

Technical capabilities for beneficial commercial RPO are functionally identical to those for hostile counter-space activities, and this is the fundamental problem. Robotic arms can service satellites or disable them. Optical sensors can inspect for damage or gather intelligence on vulnerabilities. This dual-use reality means intent, not capability, becomes the critical distinguishing factor.

This conundrum highlights a crucial governance gap. Without mandatory transparency requirements or established communication mechanisms, legitimate RPO capabilities become clouded in suspicion, especially between geopolitical adversaries. Observers cannot distinguish between nations developing legitimate capabilities and those rehearsing hostile operations. This then creates a spiral of suspicion, where even benign activities are viewed through a hostile lens.

Addressing the governance gap

The 1967 Outer Space Treaty, drafted before RPO technology existed, offers no specifics on proximity operation notifications or mechanisms distinguishing commercial from defence activities. Article IX’s ‘due regard’ principle provides foundational guidance, but the only enforcement of this is through the national regulators. Industry organisations like CONFERS (Consortium for Execution of Rendezvous and Servicing Operations) develop best practices. Whilst these are essential for shaping behaviours, the very nature of them are advisory and are not binding.

Practical transparency measures could translate abstract ‘due regard’ into concrete norms. This includes procedures such as mandatory notification when satellites manoeuvre within specified distances, advance sharing of orbital parameters and operational timelines, and protocols declaring mission intent. Ultimately, even developing a norm surrounding the ‘innocent passage’ concept drawn from maritime operations might help in distinguishing transitory approaches from provocative, prolonged shadowing.

Enforceable treaties would mandate these requirements, creating presumptions of hostility for unannounced operations. Given current geopolitical tensions and legitimate operational security concerns, this is unlikely to happen soon. States are resistant to revealing national security satellite capabilities, and this conflicts with the transparency needs for trust-building and verification. Whether norms emerge through UN negotiations, industry standards, or gradual customary practice, the current ad hoc approach, where each close approach amplifies mistrust, is unsustainable.

Moving forward

Space surveillance capabilities continue to improve, and this reduces measurement uncertainty. Yet despite tracking advances, operator intentions remain subject to geopolitical conjecture and adversarial suspicion. Without explicit mission disclosure and transparency, determining ‘how close is too close’ requires case-by-case assessment combining technical data with strategic intent evaluation. Commercial SSA providers have proven vital, enabling transparency and public discussion about acceptable orbital behaviour previously limited to governments.

Industry collaborations developing concrete behavioural norms represent vital first steps toward operational ‘rules of the road’. This will eventually lead to a translation of abstract proximity concerns into actionable requirements on all users of space to show due regard, promote transparency, and de-escalate inflammatory activities. Broad adherence would highlight malicious actors while distinguishing legitimate servicing from hostile shadowing.

Amid the current geopolitical instability, an orbital environment where every close approach triggers suspicion serves nobody’s interests. Moving forward requires all space actors to embrace more transparent, collaborative orbital operations. It is inevitable that the technology will continue to advance faster than governance adapts. The space community must look to establish transparency measures and behavioural norms enabling RPO technology to fulfil its sustainability promise, rather than becoming another conflict vector.

Please Note: This is a Commercial Profile

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International.